Hello and welcome to What China Wants.

As it’s Saturday it is time to return to the history and culture of China. It is a bit of a cheeky one today, as it’s more or less a repeat of a Tuesday post I sent out last week on the environmental and foreign currency issues that conspired to hasten the fall of the Ming.

But repeating the post is no bad thing given how important the period was. The time of the Ming was one of the most stable in the country’s history, and its end spelled the last time until 1911 that the majority Han would rule - a humiliating fact that still runs deep in the Chinese mentality today.

In case you want to read more about China’s history, here are the links to where we’ve got to so far:

Introduction to 5,000 years of Chinese history

The first Dynasty, the Xia (2070 BC – 1600 BC) – they who tamed the rivers.

The second Dynasty, the Shang (1600 BC – 1046 BC) – they who developed writing.

The third Dynasty, the Zhou (1046 BC – 221 BC) – they who started the Mandate of Heaven.

The Warring States Period (475 BC – 221 BC) – seven states and the bloody struggle for hegemony.

The First Emperor and the Qin Dynasty (221 BC to 207 BC) – he who unified China for the first time.

The Han Dynasty, Rome's Equals in the East (202 BC - AD 220) – they who established China as an international power.

The Fall of the Han - the end of the first long-lasting Dynasty, including the populous Battle of Red Cliffs.

The Tang Dynasty (618-907) - they who are still revered as the apogee of Chinese civilisation.

The Song Dynasty (960-1279) - they who nearly managed the world’s first industrial revolution, but settled for bank notes and foot binding instead.

The Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) - the Mongols rule China and try to invade Japan.

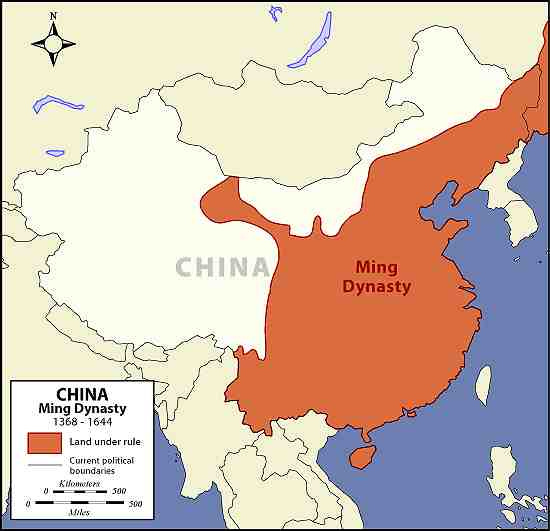

The Ming Dynasty 1368-1644) - The Han Chinese are finally back in charge, and (temporarily) opening up to the world.

As part of the historical series I’ve also done a beginner’s primer on Confucianism, which covers a bit of Legalism too.

I hope you enjoy my post below, and please remember to consider commenting, liking, sharing, and subscribing.

Many thanks for reading.

***

In a forthright speech to the US Naval College’s graduation ceremony in 2018, General Jim Mattis, the then Secretary of Defense, drew a comparison between Xi Jinping and a former Chinese Imperial dynasty better known in the West for its vases.

The Ming, who led China from 1368 to 1644, were far more than successful porcelain exporters. Although they eventually cut themselves off from the outside, the Ming were broadly an internationalist dynasty who embraced trade with the rest of the world on a scale not repeated until the opening up of the Chinese economy in the 1980s.

As General Mattis was hinting at, this interaction with foreigners was not an exchange of equals. For the Ming, according to a general scholarly view, were responsible for establishing an extensive tributary system with its neighbours. Many in Washington fear that Xi Jinping is trying to replicate this sort of relationship between China and the rest of the world, although this is something that Beijing denies.

There is, however, another important comparison to be made between China today and the former dynasty. Despite a successful few hundred years, the Ming eventually fell to two pressures that have resurfaced as potential challenges to the Chinese Communist Party today. The first was from the environment, the second was a currency embargo.

Having seen off one set of rulers, will these phenomena combine to strike again?

As I discussed recently, there is a school of thought amongst both Western and Chinese analysts that the US is gearing up for a full-on dollar blockade against China, an escalation of the economic campaign that Washington is already waging through its blacklist of Chinese firms. If this happened it would create real financial issues for a country that still spends hundreds of billions of dollars each year on food and fuel, as well as servicing its foreign debts.

It would not, however, be the first time that China suffered an embargo of this type.

Despite its origins as an agrarian, inward-looking empire, the Ming saw a steady accumulation of industrial strength and foreign trade relations as the fifteenth century wore on. Then, in 1517, the Portuguese made contact, which enabled Chinese goods including porcelain to reach the homes and palaces of Europe for the first time.

It was the Spanish, who slowly replaced their Iberian cousins as the main trading partner of the Ming, who made the most impact. Silver flooded into China, much of it in the form of dollars that had been minted in the Spanish colonies of the New World, and then traded in in the entrepot of Manila, where Chinese and European traders freely mixed.*

The sheer weight of silver now making its way into China had a particular effect on the local economy. Not only did it power a wave of excessive consumption, as the increasingly embellished hairstyles of the time reveal, but the authorities started to demand and receive tax in the form of silver.

Unfortunately for the empire’s finances, it was not to last. In the 1630s Philip IV of Spain, worried about the outflow of precious metals, cracked down on the illegal shipment of silver across the Pacific.

The effect was to cut the stream of silver into China, with catastrophic consequences. The metal’s scarcity not only made inflation spike, but also grossly interfered with the collection and payment of taxes.

The result was not hard to imagine. Rebellions broke out across the land, inspired by both the burden of unpayable tax demands, and a collapse in order created by a government no longer able to pay its way.

There is a chance that the Ming Dynasty, for all its internal issues and the decreasing quality of its emperors, could have ridden the currency storm if given enough time and an otherwise stable environment. Yet this was not to be, because of the appearance of another, far more damaging event.

The Little Ice Age was a climatic period of history that saw a world-wide drop in temperatures between approximately the sixteenth and the nineteenth centuries. In the West it is best known as the probable cause of the extinction of the Norse settlements in Greenland, and for the freezing of the great rivers of Europe such as the Thames, which enabled the holding of riverine frost fairs.

In China, the Little Ice Age led to unusually cold and dry weather, the coldest and driest for 500 years according to contemporary records. This climatic downturn led to widespread drought and famine that severely tested the land.

Added to this, the changing weather patterns unleashed a record number of typhoons onto the coasts of China, leaving devastation in their wake that the authorities could not afford to deal with.

With crops dying, infrastructure broken, and a government running out of cash and support, the bonds of public support for the dynasty began to fray.

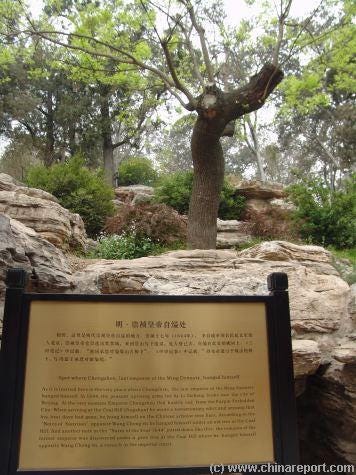

When a revolt led by a jackal-voiced bandit calling himself the “Dashing King” bubbled to the surface in the early 1640s, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of thousands, if not millions, the writing was on the wall for the regime. The last Ming emperor hanged himself from a tree, not before he slashed one daughter to death and lopped the arm off another. Not long after, a people called the Manchu invaded from the northeast, carrying the temporarily victorious rebels before them, and became the new Qing dynasty.

Thankfully for the people of China, who rightly fear the chaos of the past, there is no indication that the country is about to experience the turmoil that illuminated the end of the Ming. But with the climate emergency enduring, and relations between Beijing and Washington continuing to deteriorate, there are lessons from history to be learnt.

General Mattis was right about the similarities between the Ming and the CCP today, but the re-establishment of a tributary arrangement with China’s neighbours could be the least of everyone’s worries if the world’s second largest economy follows the fate of its forebears.

* Such was the importance of the foreign silver inflow that Chinese domestic coins were valued the same as the Spanish dollars, starting the continuing equivalence between the names "yuan" and "dollar" in the Chinese language.