5,000 years of Chinese civilisation - perhaps

China's claim to ancientness may be correct, but it's not without heavy caveats

When Chris Patten, the last British Governor of Hong Kong, was preparing a speech for his swearing-in ceremony, he saw that one of his officials had drawn a line through a reference he had made to Britain and China being “two great and ancient civilizations”. When the Governor asked why, he was told that the Chinese would be offended by the assumption of parity given that their civilisation was so much older.

In China, everyone knows that their civilisation is the world’s most ancient; five thousand years old, to be precise. It is a date printed everywhere and drilled into schoolchildren at a young age.

China’s ancientness is not just a matter of mild historical interest. As the writer John Ross notes, the concept of 5,000 years is important because of the inference that China is uniquely old and so deserves special consideration. Because the country is so ancient, so the thinking goes, you need to show extra respect and cultural sensitivity. This applies to whatever you are doing, whether it be rolling out a joint business venture, or negotiating the future of the South China Sea.

The trouble is, the concept of a uniquely long history is flawed.

The first problem is that it implies that Chinese civilisation can be understood as a single block that extends unchanged and unadulterated five millennia into the past. Like everywhere else, China has morphed and grown and absorbed other cultures and peoples, to the extent that the original lands of the Chinese on the Central Plain (roughly modern-day Henan Province) are a fraction of the territory and cultural richness of the country today.

The second problem is that there are plenty of other places that have five thousand years of history behind them. Early Dynastic Egypt, when the precursors to the fabled pyramids were built, was roughly contemporaneous with the first urban Chinese, as was one of the first inklings of Western civilisation, the Minoans. Indeed, the eastern Mediterranean has a considerable number of cities still extant today that can trace their beginnings to earlier than the first Chinese centres, cities like Damascus and Jericho, which were both founded about 9000 BC, and Argos in Greece, a comparative latecomer at 5000 BC.

Yet, this is to miss the point of why China claims its culture is so old. People living in Greece today have very little cultural similarity with the Minoans. Olive growing, perhaps, and the faint memory of their worship of the bull in the story of the Minotaur. Greeks cannot, however, understand what the Minoans wrote – no one can.

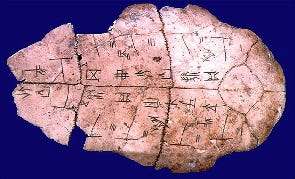

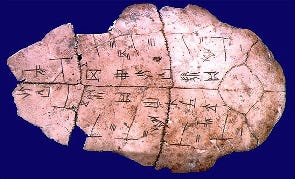

By comparison, the earliest form of Chinese writing dates back to around 3,000 BC, and uses characters that are recognisable today, including the word for “people”. Even if, as some scholars suggest, we reject these scribbles as too rudimentary to be considered proper writing, there is little debate that fully recognisable Chinese characters had emerged by the time of the Shang dynasty, which ruled from 1600-1046 BC.

There is also genetics. Whereas most French, Britons, or Americans would find it hard to find a genetic link to centres of civilisation five thousand years ago, this is not the case for the 91% of modern Chinese who are ethnically known as Han. There are clear connections between the Han and the earliest Sino-Tibetan people (to give them their proper classification) living in the Yellow River basin thousands of years ago. The vast majority of the English, by comparison, only arrived in their current land post AD 400 with the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons.

The cultivation of rice and silk – both of which are central to Chinese identity over the centuries – appeared thousands of years ago, and chopsticks were in use by 1200 BC. The fork, on the other hand, was probably invented in Byzantium in the fourth century AD, but didn’t make its appearance in Europe until the Renaissance.

Taken together, the long history of these crucial elements of what it means to be Chinese – both physically and culturally – does give the Chinese people a very real sense of connection with their far-off ancestors, to a degree not really found elsewhere. Egypt, for instance, may have the pyramids, but culturally and, as we now know, genetically, there is very little cross-over.

This does not, however, mean that this longevity should be used to further Chinese ambitions. Chris Patten ignored his official and included the line in his speech, aware that some in China would take offence. What Patten realised, and which others should note, is that ancientness of culture does not enshrine rights today. It does though provide a richness of history that can be learnt from both for utility and for interest – and which is open to the world, not just China’s current inhabitants.