Hello and welcome to What China Wants.

Today in my History of China series we look at the Ming. They are perhaps the best known of the Chinese dynasties in the West, but it is a reputation forged in the empire’s porcelain kilns rather than for any of their other achievements. There is, not surprisingly, far more to them than ceramic exports, as I explore below, including a far amount of blood.

In case you want to read more about China’s history, here are the links to where we’ve got to so far:

Introduction to 5,000 years of Chinese history

The first Dynasty, the Xia (2070 BC – 1600 BC) – they who tamed the rivers.

The second Dynasty, the Shang (1600 BC – 1046 BC) – they who developed writing.

The third Dynasty, the Zhou (1046 BC – 221 BC) – they who started the Mandate of Heaven.

The Warring States Period (475 BC – 221 BC) – seven states and the bloody struggle for hegemony.

The First Emperor and the Qin Dynasty (221 BC to 207 BC) – he who unified China for the first time.

The Han Dynasty, Rome's Equals in the East (202 BC - AD 220) – they who established China as an international power.

The Fall of the Han - the end of the first long-lasting Dynasty, including the populous Battle of Red Cliffs.

The Tang Dynasty (618-907) - they who are still revered as the apogee of Chinese civilisation.

The Song Dynasty (960-1279) - they who nearly managed the world’s first industrial revolution, but settled for bank notes and foot binding instead.

The Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) - the Mongols rule China and try to invade Japan.

As part of the historical series I’ve also done a beginner’s primer on Confucianism, which covers a bit of Legalism too.

I hope you enjoy my post below, and please remember to consider commenting, liking, sharing, and subscribing.

Many thanks for reading.

***

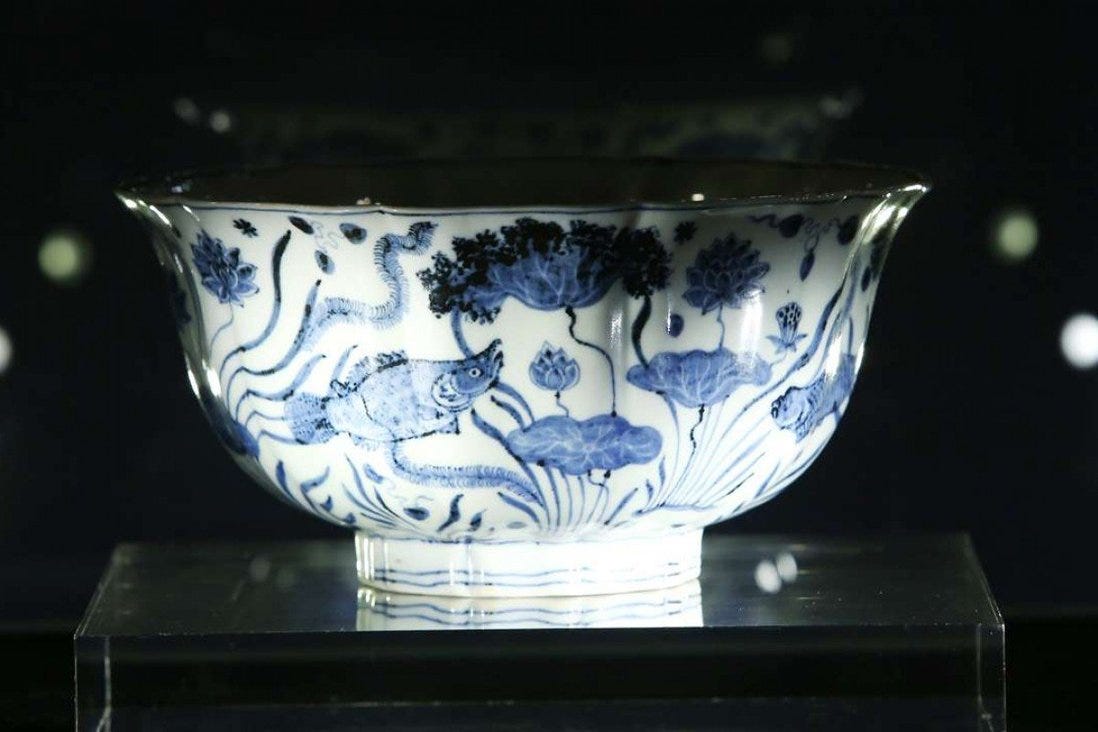

In 2017 a small, rare wine cup from the Imperial kilns, decorated with a blue and white fishpond scene, was sold in Hong Kong for US$36.2 million. Like the famous vases, Ming porcelain has become some of the most sought after and expensive of the relics from China’s past. This is partly down the exquisite workmanship of the pieces, which were unparalleled in their quality at the time, but also because of the high regard the Ming are held in as the last great Chinese dynasty.

Societies worldwide share the concept of a golden age sometime in their past, when everything was better than today. What these ages normally have in common is that they come before or after a really terrible time in the nation’s history.* In England, the Elizabethan golden age (as in, the movie Elizabeth: The Golden Age), home to early Shakespeare and the victory over the Spanish Armada, lies in stark contrast to the slaughter of the English Civil War that came not long after.

The Ming (1368 to 1644) benefit from being bookended by two unpopular dynasties, the Yuan and the Qing, both not-surprisingly foreign.

It wasn’t hard to be better than the Mongol Yuan rulers, at least if you were Han Chinese, thanks to the brutal feudalism they imposed. That said, the first emperor Hongwu – whose name translates as something close to “Great Military Leader” – was far from benign. It is said that his peasant background and the years of grinding rebellion against the previous regime made him into a suspicious and tyrannical leader, demanding overt loyalty and obedience from everyone around him. Officials who failed to kneel in his presence were beaten, and he turned his palace protection into a form of secret police, the jauntily named Embroidered Uniform Guard. In 1380 he started an internal investigation that lasted fourteen years and led to the execution of 30,000 people, many of whom suffering the new methods of torture that were being devised.

Despite the bloodshed, Hongwu set his empire on the path to historical greatness, as the name of the dynasty indicates. Ming (明) means “bright” in Chinese - as in, a beacon on the hill that everyone can see – and it is an apt name for an empire that became the most powerful country in Asia.

The Ming were militarily strong. As well as the development of a vast navy, they had a standing army that numbered a million, out of a total population of between 160 and 200 million at the empire’s height. The territory of China increased and decreased throughout the Ming period, but it did build upon and solidify its trading relationships abroad. China also cemented its influence in a number of vassal states, from Korea to Southeast Asia, that paid regular tribute to the Emperor. This wasn’t necessarily because of Chinese pressure; many nations and rulers wanted to be associated with the power of the Middle Kingdom.

It’s easy to see why when one looks at the cultural output from the Ming. Literature, poetry, and painting flourished, especially in the wealthy lower Yangtse valley, and the first newspaper (The Peking Gazette) appeared. The period was also the origin of many important traditional books of China, such as Journey to the West, which is ironically known best outside China from a Japanese TV adaptation from the late 1970s called Monkey. Another tome was Romance of the Three Kingdoms, describing the period after the fall of the Han Dynasty, and the source of the well-known quotation, “The empire, long divided, must unite; long united, must divide. Thus it has ever been".

The legacy of the artistic nature of the Ming, coupled with the bloody tendencies of its early rulers, is perhaps best summed up by the fifteenth century construction of The Forbidden City, which still adorns Beijing today.

The palace complex, covering 72 hectares, is far larger than any of its European counterparts. It isn’t even the biggest palace in Chinese history, a title which belongs to one built by the first Han emperor, Weiyang Palace, which was almost seven times as large, until it was burnt down by marauders during the Tang.

The contrast with the Versailles and Buckingham Palaces of this world is not quite right, however, because the Forbidden City served a different function to its equivalents in the West. Whereas European monarchs of the medieval period travelled around their kingdoms dispensing justice and favours, the Forbidden City was designed to be the absolute central point of the Empire. Its sheer scale – a thousand buildings, including temples and palaces, surrounded by thirty-five foot walls – reveals it as having been much more than just a ceremonial centre.

Its practical function didn’t stop it being replete with imagery to befit its status as the heart of the empire. The design of the roofs, for instance, was designed to symbolise the highest point in the social hierarchy, as are the frequent depictions of dragons, the representation of the emperor’s omnipotence.

The plethora of stone carved lions is a little harder to understand when lions aren’t (and never have been) native to China (although, to be fair, neither were dragons). The lions are instead a reference to the tributary nature of the Empire’s relationship with Central Asia, whose rulers would send over the big cats as part of their gift packages. The lion, therefore, is a totemic symbol of Chinese dominance, and so well-placed to be in the centre of Beijing.

Despite its grandness, the Forbidden City’s origin was more by accident than on purpose. Hongwu’s successor, the Emperor Yongle, had a similar penchant for violence flowing through his veins. When a Confucian scholar took umbrage at the manner of Yongle’s accession (he had overthrown his uncle, the rightful emperor), the Emperor had the man’s tongue cut out, after which he was half beaten to death on the palace floor. As he lay there dying, the scholar used his own blood to write a choice sentence of opposition against Yongle, a scarlet message that they could never wash out.

Perturbed by the Macbeth-like qualities of the spilt blood, Yongle ordered the capital moved from Nanjing to the more northerly Beijing, and the construction of the Forbidden City to house his court there. Not before he had had another Confucian scholar killed by limb-by-limb subtraction, and 873 of his closest relatives terminated.

That the Emperor was the centre of the Empire, and therefore the world, was something well understood by the time the Ming took power. What the Ming did was to strengthen this concept internally through the construction of the new palace in Beijing, as well as many other reforms that helped to turn the Dynasty into one of the most unchallenged in the country’s history.

The Ming also sought to develop the concept of the Middle Kingdom abroad, much more than before. To do this it used its economic power, which was strongly supported by the mass export of china and other craftsman-produced goods, like the vases we see at auction today.

This economic activity was intrinsically bound up with Chinese forays abroad, as seen by the Zheng He treasure fleets, and an increasing focus on tributary relations with his neighbours.

All of this economic activity, which brings together the discovery of the Americas, the Spanish settlement of the Philippines, and the first experiments with a global economy, will be discussed next time. As will the role of the environment in the ultimate collapse of the Ming, a timely reminder with COP26 about to start, that not even the most powerful of empires can withstand sudden and detrimental climate change.

* For a really good discussion on golden ages, listen to the Rest is History podcast on the subject, with Tom Holland and Dominic Sandbrook.