Hello fellow China Watchers,

Today in the History of China we look at the Song Dynasty (960-1279). The Song aren’t much known in the West, but in many ways they were more impressive than the preceding Tang, who are considered the apex of Chinese civilisation.

Trade flourished, as did innovation, and many of the “Big Four Inventions” we discussed in the Needham Question post were born here. Sadly, another legacy the Song was responsible for was a cultural practice that some historians have called the worst mass assault ever performed on humanity: foot binding.

In the meantime, if you missed any of the History of China series, then here are some links to where we’ve got to so far:

Introduction to 5,000 years of Chinese history

The first Dynasty, the Xia (2070 BC – 1600 BC) – they who tamed the rivers

The second Dynasty, the Shang (1600 BC – 1046 BC) – they who developed writing

The third Dynasty, the Zhou (1046 BC – 221 BC) – they who started the Mandate of Heaven

The Warring States Period (475 BC – 221 BC) – seven states and the bloody struggle for hegemony

The First Emperor and the Qin Dynasty (221 BC to 207 BC) – he who unified China for the first time

The Han Dynasty, Rome's Equals in the East (202 BC - AD 220) – they who established China as an international power

The Fall of the Han - the end of the first long-lasting Dynasty

The Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907) - they who are still revered as the apogee of Chinese civilisation

As part of the historical series I’ve also done a beginner’s primer on Confucianism, which covers a bit of Legalism too.

I hope you enjoy below, and please remember to consider commenting, liking, sharing, and subscribing.

Many thanks for reading.

***

All good things must come to an end. The Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907), a high-water mark in Chinese culture, trade, and power, began to wane after the An Lushan rebellion of 755. As I wrote last week, this was one of the bloodiest wars in history, and which may have accounted for the deaths of up to one sixth of the world’s total population.

The last hundred and fifty years of the Tang were wracked by further disaster. Many were natural, including floods and droughts. Others were in the form of further rebellions by regional generals taking advantage of the decline in the Emperor’s power that An Lushang had done so much to foster.

Finally, in 907, the last emperor was deposed, ushering yet another period of inter-dynasty chaos, this time called the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. Thankfully for those in favour of peace and harmony, this interruption didn’t last long, and in 960 the new Emperor Taizu spent the next sixteen years reuniting much of the land that had belonged to the Tang, creating as he did so the foundation of the next Dynasty off the block: the Song.

Although it doesn’t quite compete with the Tang in terms of historical popularity, the Song Dynasty is officially recognised as a good age. For the most part it was a time of internal tranquillity, booming trade, technological innovation, and cultural sophistication. About six million people lived in cities, perhaps as many as lived in cities in the rest of the world put together. Indeed, the combined population of just two cities - the Song capitals at Kaifeng (today a middling city in Henan Province) and Hangzhou (which lies close to Shanghai) - was around two million, more than the total amount of people living in England under William the Conqueror.

Significant advances in agriculture underpinned much of the Song’s success. The government started to grant ownership of land to farmers, which encouraged more land to be taken into cultivation. As much of this land was marginal, new technologies were needed, like fast growing seeds and steel ploughs, and the result was a hefty rise in food surpluses. Economic crops like cotton, hemp, and increasingly tea, were all grown too.

There were other successful government adjustments to the economy. Song merchants were encouraged to set up a type of joint stock company, guilds were established in the cities, and government-run industries grew hand in hand with the myriad small businesses that flourished at the time. It wasn’t just men who were involved in business. Women under the Song had a degree of economic independence that was previously unknown. Not only did they participate in the silk and weaving industries, but they were also able to hold property and inherit in their own name. Some women gathered great fortunes as a result.

However, this was a temporary triumph for womankind. A rebirth of Confucian ideals, partly as a further reaction to Buddhism, led to a slow division between the sexes as women were increasingly kept secluded from men. Their property rights were dismantled, and they were encouraged to live a stricter moral code, for example being required to stay at home more, so as to look after the children.

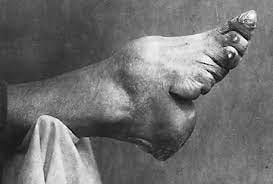

As John Keay discusses in his book China: A History, the apogee of control over the female half of the population came with the popularisation of foot-binding. Considered a sign of femininity, of status, of beauty, and of refinement, foot-binding required girls as young as five forced to wear tight bandages that shrank and morphed their feet into little more than fleshy ornaments, barely fit for walking. Much like the spread of the modern-day burqa, which even as late as the 1960s was a rare sight in Islamic societies, foot-binding was very quickly adopted by the upper echelons of society between 1086 and 1100, and was then adopted more widely. As many as a third of Han women (non-Han women shunned it) were made to suffer the agony of disfigured feet for the next eight centuries, and as Keay notes, it probably added more to the sum of human misery than male castration, female circumcision, and all other custom-endorsed outrages combined.

Still, for the male half of society, particularly the merchant class, life had never been so good. The economy went from strength to strength, and such was its growth that the traditional coinage system couldn’t keep up, hastening the adoption of the first state-level use of paper money. Whilst there is evidence that Carthaginians produced an early form of banknote in the form of promissory notes, as did the Tang, it was the Song who are credited today with being the originators of the modern use of paper cash.

Banknotes were needed partly because of the boom in foreign trade. Shipborne commerce increased under the Song, linking the empire with Southeast Asia, India, Arabia, and even the Byzantium Empire, which despatched embassies as the Romans proper had done so before. Overland trade was trickier, in part because the Silk Road that went westwards through today’s Xinjiang province had been captured by foreigners at the fall of the Tang.

Yet, for all their economic strength, the Song were militarily weak. They did have a good navy, designed to protect their trade, and which was armed with inventions like bomb-launching catapults that made use of gunpowder for the first time. On land it was a different matter, and this was to prove their downfall.

To the northeast of China, in and around today’s Manchuria, lived the Jurchen peoples, more closely related to Mongols than the Han. The Song had long used these horse-backed warriors to fight other nomadic peoples - a strategy that backfired when the Jurchen came to understand why they were being used. The Song armies, they realised, were weak and ineffective, and what’s more, had proven themselves unable to deal with massed ranks of steppe cavalry.

From the year 1125 the Jurchen turned on their allies and invaded Chinese lands, capturing huge swathes of territory. Their conquests stretched from the border of Korea to the Central Plains, which, humiliatingly enough, were the cradle of Chinese civilisation. Much of the later Song poetry is obsessed with the sadness of having lost the Han’s heartland.

However, not all the Song lands were taken by the Jurchen. The Dynasty continued (under the banner of the “Southern Song”) for another century or so, until another army from the steppe invaded and finished them off. This group of tribes wiped out the Jurchen too, and thus reunited China for the first time in generations under yet another dynasty, the Yuan. Or, as they are better known today, the Mongols.