Yu the Engineer and the Great Chinese Flood

Chinese history 1: Taming China's rivers four thousand years ago

Before we get going on this week’s cultural and historical post, I had some interesting feedback from a reader on my Jack Ma disappearance piece: apparently, Jack knew the Ant IPO was going to be cancelled - and that’s why he gave his now infamous speech. An interesting one to ponder.

As for my Saturday posts, over the coming weeks I’m going to take you on a whistle-stop tour of China’s history, looking especially at some of the extraordinary people that have made the country what it is today. It can’t be exaggerated how important it is to understand China’s past if you want to know its present.

Finally, thanks to everyone who shares my posts (and a lot of you do) - please continue to do so, and if you really want to be kind, get them to subscribe as well!

***

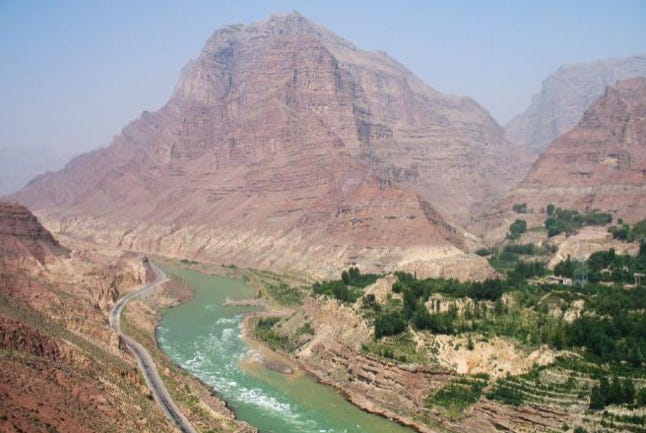

China is geographically and historically intertwined with its rivers. It was the Yellow River, in the north, that cradled the nascent Chinese civilisation. The Yangtse, to the south, and with Shanghai at its mouth, has been the aorta of national trade for centuries.

The rivers have a dark side too, namely their habit of rising up and killing people. The 1931 Yangstse floods drowned 140,000 men, women, and children, and up to four million more through the resulting disease and famine. The 1887 floods killed perhaps two million, the 1935 floods accounted for 145,000, and the 1911 inundation left 100,000 dead.

If this is the toll in just the last century and a half, and after thousands of years of river management, it is little wonder that whoever was able to come up with a way of taming the water in ancient times would have been feted. Yu the Great, or Yu the Engineer as he is sometimes called, was that man.

The story of Noah has an echo in Chinese prehistory, namely “The Great Chinese Flood”, which is said to have happened about 2000 BC. “Like endless boiling water, the flood is pouring forth destruction” is how the mythical ruler of the time, the Emperor Yao, described it. “Boundless and overwhelming, it overtops hills and mountains. Rising and ever rising, it threatens the very heavens. How the people must be groaning and suffering!”

In the wake of the tragedy, a man called Yu was tasked with controlling the floods. The story goes that he learned how to do so by dredging the rivers and establishing irrigation canals into which the water could flow – or, alternatively he did so with the help of a turtle, a dragon, and a divine axe. Whatever he did seemed to work, because Yu became one of the only kings to possess the epithet “the Great”, and he went on to establish one of the foremost dynasties in Chinese prehistory, the Xia.

Yu is still spoken of today. When the Three Gorges Dam looked like it might be in danger of collapse in August last year – which, as the only thing standing between 39.3 billion cubic meters of water and 500 million people downstream, would have been catastrophic to say the least - President Xi visited the site. Inspecting the flood defences, he praised China’s long fight against natural disasters, including “Yu’s treatment of water.”

In China, the division between history and myth is often blurred into deeply entrenched stories that are passed down the generations to the extent that they become an essential part of what it is to be Chinese.

Just because a person or an event in the distant past can’t be fully proven by the historical sources doesn’t mean that they can’t become history. Take Yu’s own dynasty, the Xia. Long considered by scholars to be mythical, a 1996 report commission by the Chinese Government not only concluded the Xia were real, but even gave them definitive dates, from 2070 BC and 1600 BC.

There is also evidence that suggests that The Great Chinese Flood may have happened after all.

According to a 2016 paper in Science, a massive landslide deposited rock and sediment into the Yellow River, creating a dam half a mile long and some 660 feet tall. The river was cut off for months, the water building up and up behind the earthen wall. When the dam finally burst, nine months of rainfall was released in a matter of hours, creating a flood up to a hundred and thirty feet high that devastated the land.

Yu the Great may or not have existed; it doesn’t matter. What is important is that his legacy continues today, and is used by the Communist Party to invoke lessons from the past and thereby to stimulate the people. As The Three Gorges Dam shows, there’s nothing quite like a huge nature-taming project to tell the public who’s in charge.