Dear all

Today in the History of China we discuss the end of the Han Dynasty (202 BC – AD 220), the first long-lived dynasty to rule over a united China.

As we explored last time, the Han and the Roman Empire had more in common than just existing at the same time. They were both powerful civilisations with substantial populations and a high level of urban civilisation, and there was a degree of trade between them too. What they also shared was that they were both brought down in part by the same nomad-inspired pressures, which we will cover today.

In the meantime, if you missed any of the History of China series then here are some links to where we’ve got to so far:

Introduction to 5,000 years of Chinese history

The first Dynasty, the Xia (2070 BC – 1600 BC) – they who tamed the rivers

The second Dynasty, the Shang (1600 BC – 1046 BC) – they who developed writing

The third Dynasty, the Zhou (1046 BC – 221 BC) – they who started the Mandate of Heaven

The Warring States Period (475 BC – 221 BC) – seven states and the bloody struggle for hegemony

The First Emperor and the Qin Dynasty (221 BC to 207 BC) – he who unified China for the first time

The Han Dynasty, Rome's Equals in the East – they who established China as an international power

As part of the historical series I’ve also done a beginner’s primer on Confucianism, which covers a bit of Legalism too.

I hope you enjoy below, and please remember to comment, like, share, and subscribe.

Many thanks for reading.

***

In his book “War! What is it Good For?” the historian Ian Morris notes that for both the Han Dynasty and the contemporaneous Roman Empire, the peace they had enjoyed for hundreds of years started to fracture in the early to mid second century AD, and for similar reasons. The peoples of the steppe – that band of grassland running across Eurasia from Mongolia to Hungary – had spent a long time perfecting the use of cavalry, and from the second century started pushing east and west at the same time, possibly because of climate change.

Whatever the reason for this mass movement, the results were devastating. In the West, and from about the year AD 166, the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelias found himself fighting hordes of Germanic invaders, who in turn had been pushed off their lands by steppe tribes like the Sarmatians. Although the Western Roman Empire held the barbarians off for another two centuries, the invaders from the steppe would be a critical reason for its eventual downfall.

In the East a similar story was unfolding. The Steppe-living Xiongnu people had long been a thorn in the northern frontiers of the Han, but by the early AD 100s their pressure reached a point where the Dynasty lost control of its borders. As Morris notes, a Chinese official lamented that “even women bear halberds and wield spears, clasp bows in their hands and carry arrows on their backs”.

(As an aside, there is a long-standing, but disputed, hypothesis that the Xiongnu went on to become the Huns, those other steppe warriors who brought to much pain to the Romans in the fifth century under their leader Attila.)

This instability was the beginning of the end for the Han. The second century had started badly, but got worse with a major earthquake in AD 133 and a drought the following year. The Emperors were unable to provide any stability thanks to intrigues at court, often centred around the senior eunuchs who by this time had become a ruling class almost unto themselves. The last nine Han rulers all had suspiciously short lives, and not one of them was an adult at the time of his accession.

To add to the Empire’s woes, revolts broke out across the country from the latter part of the second century onwards. In AD 184 the Yellow Turban Rebellion started, triggered by crop shortages and high taxation, and led by fanciful characters like “Ox-horn Zhang” and “Zuo of the Eighty-Foot Moustache”. The Rebellion took over two decades to be suppressed, giving more succour to the feeling across the land that the Mandate of Heaven was starting to shift away from the Han.

By now the process of dynastic coming and going was well established, as recorded in the opening lines of one of the most famous of China’s books, The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, by Luo Guanzhong: “The empire, long divided, must unite; long united, must divide. Thus it has ever been.” Although The Romance of the Three Kingdoms wasn’t published until the fourteenth century, the majority of the thousand or so characters described in the eight hundred thousand words of the book are broadly historical. The plot starts in AD 169 on the eve of the events that led to the downfall of the Han, as a court riven by rebellion, corruption, and weak Emperors descends into chaos.

The tipping point in the decline of the Han was the assassination in AD 189 of the military Grand Marshall of the empire, He Jin, by a group of court eunuchs in a last-man-standing dash for power. The eunuch-officials in turn were massacred by supporters of the general, and from there events spiralled out of control to consume the whole empire.

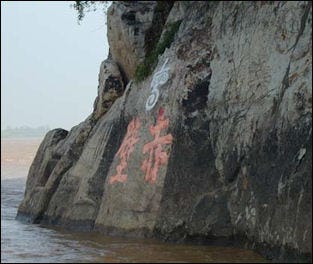

Amidst all the bloodshed that followed, the best-known confrontation was the AD 208 Battle of Red Cliffs, the subject of John Woo’s 2008 eponymous film. As this is probably the most famous battle in Chinese history before the modern day, as well as one of the world’s largest naval battles, it’s worth a fleeting description.

On one side was the warlord and poet Cao Cao, who today is still reviled as a villain and a usurper by the Chinese public. With the Han Dynasty on its knees, Cao Cao saw the opportunity to take power for himself and establish his own dynasty. In order to do so he had to conquer the south, and so assembled an army of perhaps 800,000. Facing him over the Yangtse River were the southern generals Sun Quan and Liu Bei, who could only muster an army of 50-80,000. Their key advantage, however, was that half this small force was trained in naval warfare, whereas most of the northerners were callow recruits.

Cao Cao built an invasion fleet to cross the river, and so as to stop his young soldiers from being seasick, chained the boats together. The southern generals saw this and dispatched fire ships along the river, which destroyed Cao Cao’s fleet because they couldn’t escape their chains. Those soldiers and sailors that weren’t killed on the river were cut down on the banks by the waiting southern army.

The result of the battle, apart from a ferocious loss of life, was the definitive splitting of China into three kingdoms. Yet these constituent parts didn’t last long, and the coming centuries saw a plethora of successor states rise and fall. As the historian John Key says of the period, it was four hundred years of vicissitude.

Out of change comes opportunity, for some at least. Large numbers of people immigrated into China’s territory, especially from the northern steppe peoples. Such was the inflow of people that the population remained static despite the enormous bloodletting that characterised the period, probably not far off the 60 million recorded in the census of AD 2. This demographic transformation encouraged the establishment of “proper” Chinese culture, like calligraphy and poetry, as a way of differentiating against the newcomers. In a similar vein Taoism, what is the closest the Chinese have to a national religion (assuming Confucianism to be more a way of thought) took deeper root.

Buddhism also continued to grow. The establishment of Buddhist nunneries gave women a new way of life, but it wasn’t the only way that female life evolved. So many men were away fighting that women were forced to adopt roles that had previously been for men only, with some even taking up blades. Many of China’s legendary female characters emanate from this time, like Hua Mulan, the legendary star of two Disney films, who is known for taking her father’s place in the army to fight the invading swarms.

Finally, in the 580s, a man named Yang Jian accumulated enough power to reinstall centralised Han control of China and establish the Sui Dynasty. The Emperor Wen, as he became upon his coronation, was eager to bring back greatness to his lands and so embarked upon an ambitious rebuilding programme. Such was the tax and manpower drain that the Mandate of Heaven barely lasted a quarter of a century before the next Dynasty was ushered in. It was the start of the most famous Dynasty in Chinese history, the Tang, who we will look at next time.