Hello and welcome back to What China Wants.

Today we return to one of our audience’s favourite topics, the economy of China. Sam interviews Stewart on the latest figures and what this means for the rest of the world.

Here are some highlights of our discussion:

Economic figures for the last year show that China’s state sector outperformed the private sector. The problem is that the private sector is much more efficient than the state, and so as the former struggles it will impact negatively on the wider economy.

We will likely see solid growth return soon. A key driver of domestic growth in China post-Covid is likely to be domestic tourism.

But China’s investment to GDP ration has been running very high for many years, leaving China with a capital stock that is much higher than other countries. This is the same situation that Japan found itself in before its 1990s economic bust.

In the long term there is a question as to what role foreign capital plays in China. For instance, by default the parts of the economy that Beijing wants to drive forward are important to the state, and so foreign capital may not be wanted there.

The trouble is, no country can offer what China can when it comes to its manufacturing scale, so not many countries can eat China’s lunch there.

China’s economy is likely to be less commodity intensive moving forward, and so this may be bad news for countries like Australia.

Decoupling between China and the West continues.

Because of the headwinds facing it, there is a good chance that the Chinese economy won’t be that much bigger in ten years than it is now.

You can also listen to the podcast on Apple, Amazon, or Spotify.

As always please do share, comment, and subscribe. We’ll be back soon with more What China Wants.

Many thanks for listening.

***

Here is the transcript:

Sam Olsen: Hello, and welcome back to What China Wants with me, Sam Olsen. Today I am going to be interviewing not a guest, but my co-host, Stewart Paterson, on the state of China's economy. Now, obviously, a lot of people listening to this podcast have a stake in what China's economy is doing around the world and they might have exposure to the Chinese economy directly itself. But one of the things that everyone has in common is that no one really knows what is going on, other than perhaps Stewart.

Stewart, we are going to be talking today about its state and about how things have gone right or wrong for it in the last year or so and what you expect moving forward. But could you just sum up in one sentence, is the Chinese economy doing well or doing badly at this present second?

Stewart Paterson: Oh, well, I am an economist so I cannot give you a one word answer, Sam. It is doing very badly relative to what people are used to out of China. But clearly, the relaxation of the COVID restrictions are giving China a fillip at the moment. So, let me just put that in a little bit of context for you. In 2022, the year that just finished, according to the official data, China's GDP grew by 3%, which sounds pretty good in comparison to our own growth rates. But for context, with the exception of 2020 - the big Covid down year as it were, in which according to official numbers, China's economy grew by a little over 2%, although, obviously, that is highly questionable - the 3% growth in 2022 would be the worst year of economic growth in China since 1976. So, it does actually represent a very poor performance for China. There are reasons for that, obviously, with the lockdown, but it is an indication I think of where the new normal will be.

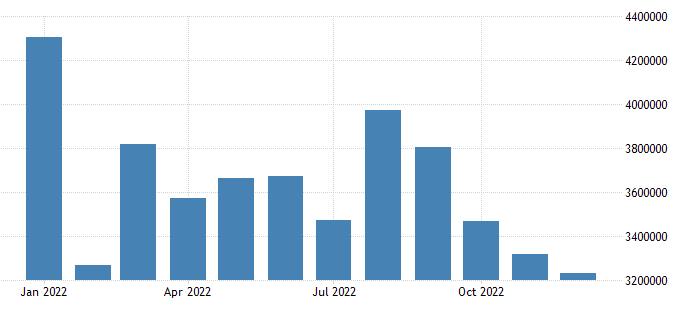

What is quite interesting, I think, is if you drill into the numbers for last year, because there are a couple of trends that are apparent. The rural economy did better than the urban economy. So, household consumption amongst the rural population was significantly stronger than amongst the urban population, where actually consumption expenditure and urban population in real terms actually shrank a little bit. The other issue is state versus private, and there is quite a stark dichotomy there. For example, if you looked at fixed asset investment, that made by state-owned enterprises (SOEs) grew by 10%, whereas the private sector grew by just 1%. Those are nominal numbers, so private sector fixed asset investment in real terms probably shrank.

There is a slight dichotomy there between foreign and domestic as well. So, the foreign shrank by 5%, whereas domestic-funded fixed asset investment grew 5%. What we have been saying for a long time - and I think most people would agree with us - is that the most efficient use of investment expenditure has, broadly-speaking, been the private sector in China. And although the gap has narrowed between foreign and domestic, the foreign investment is also a sort of productivity-enhancing element to that fixed asset investment. Both those areas are in retreat and that is a big cause for concern going forward.

SO: Stewart, that is interesting that you say about the private sector shrinking. Well, we have known for the last few years that the private sector has been attacked by the government, whether it is the property sector, or technology. We also know that the private sector has been a massive generator of jobs and productivity for many years now. So, my question to you is, if we continue to see a political attack on parts of the of the domestic private sector, doesn't that mean that we are looking at a brake on growth over the next few years, even with the fillip provided by the freeing up of the economy?

SP: I think the short answer is yes, it does. So, the fundamental problem that China faces with its economic model is excess investment, and malinvestment, low-yielding investment. China's investment to GDP ratio has been running at extremely high levels, in excess of 40% of GDP now for many, many years. That, over time, builds up a capital stock that is much larger than other countries in proportion to its GDP. This excess investment has been far greater than we saw in Japan, for example, in the run up to its sort of economic bust in the late 1980s, early 1990s.

The incremental capital output ratio - the amount of GDP growth that you get for a unit of investment - has been declining very sharply in China, reflecting the inefficiency of that investment. If what we are seeing in China is actually an increase in the proportion of investment that is inefficient, and a shrinkage in the small amount of investment that has actually been driving growth, then that is very bad news indeed, because the incremental capital output ratio will continue to deteriorate, leading to less efficiency. In our report that we put out for the Evenstar Institute a couple of years ago, it was entitled "China's bloated capital stock and the lost decade", what we were arguing there was that China's economy would struggle to grow at all, if they did not address the inefficiency of investment. What this data seems to suggest is that they are not addressing that inefficiency of investment. In fact, it is getting worse.

SO: Okay, so where are the bright spots for the Chinese economy moving forward? If you were sitting there as a foreign investor into China, what sectors would you be most excited about?

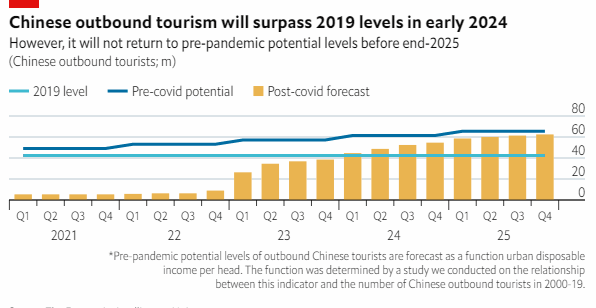

SP: Well, I think there is a difference to be drawn here between the short-term, by which I mean the next couple of years, and the longer-term outlook. If we start with the obvious sectors that were impacted heavily by the COVID restrictions, domestic tourism fell from about a RMB 7 trillion business and then fell about 80% as a result of Covid. Obviously, when you come off such a low base, you get very spectacular growth numbers coming through. The addition of RMB 3 trillion to RMB 4 trillion to GDP from that sector recovering over the next couple of years will provide a fillip to the Chinese economy that means that it might well be able to beat the 3% growth of last year, this year and the year after potentially. That is the sort of main short-term driver of better growth, although obviously that is contingent upon the parts of the economy that performed last year not deteriorating substantially. We can talk about that but there are question marks over some of it.

Longer-term, looking forward, I think the jury is still out as to what role foreign capital actually has to play in China. Remember, China has plenty of excess savings of its own, and at the moment, the politics behind foreign involvement in the economy seem to be decidedly unfavourable. So, looking at it from an investor's point of view, you have to consider the jurisdictional risks that you're going to be taking there. Obviously, the parts of the economy that the Party-State are trying to drive forward, are almost by definition, very sensitive to the Party-State, and therefore foreign participation in them is either limited or tightly scrutinised, and potentially not even welcome. And so that puts foreign investors in a big conundrum; they do not have good visibility as to what kind of operating environment they will be facing over the medium-term in China.

SO: Stewart, so in terms of foreign investors into China, that is all very well, but what about foreign investors outside of China reliant on the Chinese economy, for example, commodity producers in Australia? How do you think that they are going to fare in the next few years with the Chinese economy, in terms of what the Chinese economy needs from the rest of the world?

SP: Well, I think Sam, in that particular case, there are two very strong headwinds. The first is that China's economy is going to become less commodity intensive, as we move forward, and the mix of commodities that it uses, are going to change very dramatically, as steel production goes into decline, for example, but electric vehicles rise. And so, that is going to lead to a sort of geographical shift, and the shift in who benefits from that commodity importation. The second thing is that under dual circulation strategy, looking at China's imports through the prism of national power and great power competition, clearly there is a move by China to diversify supply, with preferred supply coming from countries over which it maintains substantial levels of structural influence in order to guarantee the solidity of that supply.

And so, those factors combined mean that again, the outlook is very unclear for people and probably disappointing relative to the way it has performed in the past. And so I think, you know, there is a general recognition that less growth in China and more strategic thinking from China in terms of where its imports come from, in terms of looking at the geoeconomic potentiality of imports, mean that it is a less attractive market from a pure profit maximisation standpoint.

SO: And how does this impact the relationship between China and the West? Now, we have spoken many times before about the decoupling that is happening between China and America, and China and other countries in the Western alliance. But how do you think things are going to change in the next few years, with all the things you have just said, coming to fruition?

SP: There are indications of decoupling. I think the most obvious one is in the foreign investment flows, both into China and the wave of capital flowing out of China is being orientated towards the global south and away from the large Western economies - the EU, the United States, etc. So, there is evidence there. The United States remains China's largest export market, so China has not managed to diversify away its exports as substantially from politically sensitive countries as it perhaps might have liked. But on the import side, China has moved substantially away from the EU, and the US, of course, was never a great source of Chinese imports anyway.

So, I think the decoupling is there. I do not see any evidence that it is going to slow down, I would suggest it will increase. And the reason for that is that multinationals are becoming more aware of the jurisdictional risk. They have suffered, obviously, during COVID, and from the sort of geoeconomic policies of both sides in terms of piling on costs of doing business in both jurisdictions, both Western jurisdictions and China. And that is starting to sink in, and obviously, these companies cannot reorientate supply chains in very short order. This takes years of planning. Vietnam has enjoyed a substantial success in attracting manufacturing. But it can only grow so fast in terms of accommodating those that shift out of China. And so, this is many years in the making, but I think that psychologically, that break has been made now. And therefore, it is a matter of time before it starts to flow through into data in a more apparent way.

SO: Okay, so Stewart, what relationship do you think that companies in the West should have with China moving forward? Do you think that there should be optimism about investment, into China and also accepting of investment from China outwards? Do you think there should be optimism about that? Or do you think that, given the geopolitics around Taiwan and the perhaps further fall in relations between China and America that looks likely to happen over the coming years as America pushes back on China's rise. Would you advise, rather than being more investment-happy, do you think that companies should be more circumspect on engaging with China economically?

SP: I think very much so. First of all, just looking at a profit maximisation model, and what prospects China holds out for you, this over-investment that we have talked about a lot means that returns on capital decline, because you are getting less GDP out of every unit of capital, and therefore the profitability of investment is massively diminished. So what we have seen, for example, prior to 2021, was a stagnation of corporate profits in China over the preceding seven years. Corporate welfare from the Chinese Party-State to support corporates during COVID led to a rise in in corporate profitability, but that has started to unwind. Last year, for example, corporate profits amongst industrial companies fell, down about 5% year-on-year. Interestingly, state-owned companies saw their profits grow, so the fall amongst private sector companies was larger.

I would not read too much into that one year simply because obviously, the state tends to own a lot of the commodity producing companies such as oil and gas and coal and what have you. And those companies did well, in the particular environment of higher energy prices. And so there is an element of that baked into it. But the core structural decline in returns on capital in China is still very evident, and that does not bode well for the profitability of foreign investment in China. So, even leaving aside the jurisdictional risk, there are good fundamental economic reasons to be very circumspect about the outlook of profitability coming from China. You have got slower top line growth, you have got a shrinking population, and you have got a bloated capital stock. Those are not good ingredients for good returns on investment.

SO: Okay, so would you be looking somewhere else in Asia, for your investment? I mean, is Southeast Asia trying to capture some of China's lunch or are the options for international investors and international businessmen and businesswomen very much restricted? I am thinking perhaps about the garment industry or other manufacturing sectors, because it does not seem to me that, despite there being a big call on divesting away from China, that companies have been divesting away.

So then it makes me think it's not just about the profits, and so on. But it is actually the use of China's manufacturing hub, given its capabilities, and its breadth of experience, that is going to be much harder for people to move away from rather than those people that just want to sell things into China. And obviously, you have explained very well the difficulties there, but from a manufacturing point of view, is there anything that people should be worried about? And why aren't people divesting away from it as quickly as perhaps American government and others would like them to?

SP: Well, there is capacity constraint; there is no single country in the world that can offer China's scale and competitiveness in terms of manufacturing. I mean, that is evident, I think. China has invested a huge amount in its infrastructure around trade, so ports, rails, technology. Countries such as Vietnam, Indonesia, India, Bangladesh, Cambodia, that have been taking lower-end manufacturing from China for a while, do not have the capacity as things stand at the moment to dramatically up the quantum of investment there and therefore take market share any faster than they are doing.

But there is a lot of evidence I think, that greenfield investment into China and manufacturing has collapsed, that we are moving away from the 'China + 1' sort of supply chain ethos, to a more diversified, friend-shoring or nearshoring model. You are seeing manufacturing investment into Mexico picking up very substantially. The European corporates are looking at Eastern Europe and Africa as alternatives to the Far East that have been driven not only by geopolitics, but by the sort of green agenda and concern about the potential for disruption to supply chains, and therefore, the pure merits of diversification. And so, I think that this is an ongoing thing and it is well underway.

SO: Stewart, in the report you wrote for Evenstar on the property sector a couple of years ago, you said that the sector posed a critical risk to the economy, the financial sector and government finances. So how has that panned out, and can the sector bounce back to drive economic growth again?

SP: It is a good question, Sam, because over and beyond the rebound and economic activity from the opening up from Covid, we require a structural driver for the Chinese economy, and we require at least something that is going to compensate for the drag that is likely to come from real estate. As you rightly point out real estate had become a huge part of China's GDP. So, in 2022, what we saw, really for the first time, was a decline in the level of investment in real estate; it fell 10% year-on-year. But what is interesting about it is that that actually did not result in any deleveraging of China's property companies.

So going into the year, real estate developers had total liabilities of about RMB 91 trillion, which is about 80% of GDP. That is where the systemic threat to the financial system lies. And the rationale behind China's 'Three Red Lines' policy was to encourage a de-leveraging of these property development companies. The problem is that de-leveraging your balance sheet into a declining market is incredibly difficult, which is why China had left it too late. So while overall investment into real estate last year fell 10%, what is interesting is that new starts of property actually fell by 40%. Sales were down 25%. But the inventory of property that is still under development, as it were fell a very modest 7%, and it is still at about 9 billion square metres of property under development, which is seven years of sales.

So, there is not really, in my view, any light at the end of the tunnel in the real estate market. We were in a situation where China was massively over-building. And what we have seen so far is a collapse in the land sales, followed by a collapse in the housing starts, the new housing starts. But what we have to do is shift this level of inventory that amounts to seven years of sales as things currently stand, in order to facilitate a deleveraging of the property developers' balance sheets. And so, the systemic risk remains and I think people holding their breath for a recovery in the real estate market to be a driver of Chinese growth are barking up the wrong tree.

SO: Ok Stewart, so what knock on effects will this structural decline in the property market have on other parts of the Chinese economy?

SP: Well, I think severe ones Sam. Although real estate development was only about 7% of GDP directly, construction is a large part of GDP as well. And obviously, real estate development is a source of demand for steel, for cement, and construction workers. What you are seeing now is a big drag on household income growth, as employment opportunities in China are starting to diminish. So it has been well reported the sort of surplus supply of graduate labour coming into the Chinese labour market. But at the lower end of the spectrum as well, you have substantial numbers of construction workers being laid off, and that is starting to impact household income growth. So we are now starting to see a stagnation in urban household income growth, which is feeding into a stagnation of urban household expenditure as well.

And so, if you like, the big hope of a lot of multinationals was that China's economy would rebalance away from investment towards consumption, driven by households in urban areas. That does not seem to be happening at the moment, which is a big challenge to a lot of the companies that have invested heavily in their businesses in China, revolved around the assumption that consumption would grow very quickly. So we will see how the relaxation of Covid regulations impacts consumption over and beyond domestic tourism, which is the obvious place. But there is a lot to prove here for people who have been arguing that the economy will be rebalanced towards consumption, because there is no evidence of it yet.

SO: Okay. Well, Stewart, thanks very much for that. It is a good place to ask this last question, which is, looking ahead five to 10 years, how do you think China's economy will perform?

SP: Well, I would refer people to this report we wrote about the bloated capital stock. The scenario we paint in that report is one in which 10 years from now, in dollar terms, the Chinese economy might be really only very marginally larger than it is now, if at all. And I think that is based on very sound analysis of the impact of declining working age population, combined with an inefficient and bloated allocation of capital.

SO: Well, that is a slightly pessimistic note to end, but thank you very much Stewart. We will be back next week for more What China Wants, and I think we are going to be looking more at the political side rather than economic side next week, but to be confirmed. Goodbye, everyone, thank you very much.

Episode 40: The Latest Outlook for the Chinese Economy