Hello and welcome back to What China Wants. There has been a lot of noise in the last few years about China’s use of its tech industry to spy on the West, as demonstrated US attempts to get Huawei banned.

Today we discuss another potential technological vulnerability, something that is really not well known, but which has the potential to be far more widespread than Huawei ever could. Cellular Internet of Things (IoT) components are ubiquitous in devices in the home, in the car, and at work - and China makes most of them.

To discuss the threat, Sam and Stewart are joined by eminent China watcher and former diplomat Charlie Parton to discuss a paper he has written on this very topic.

A summary of our discussion:

Cellular IoT modules are small pieces, only a couple of centimetres squared, but very powerful and embedded with sensors, software, antennae, and geolocation capability. They connect to the internet, rather like your cellular phone does.

They pass data to and from each other, and they have the potential of passing the data back to the people that manufacture them.

Chinese companies like Quectel or Fibocom have an almost monopoly on their manufacture. Thus cellular IoT modules, when installed in Western devices, can send data back to China.

Much of this data can be very sensitive, for example spotting where a car is parked (thus potentially unmasking MI6 or CIA agents if they are parked at Vauxhall or Langley). It is likely that the component the British authorities just removed from a Ministerial car was a cellular IoT module made in China.

Western companies do manufacture these components, but are often restricted in their success by unfair Chinese subsidies.

The West needs to take this threat seriously and find a way to marginalise China’s presence in the cellular IoT market.

You can also listen to the podcast on Apple, Amazon, or Spotify.

As always please do share, comment, and subscribe. We’ll be back soon with more What China Wants.

Many thanks for listening.

***

Here is the transcript:

Sam Olsen: Hello, and welcome back to What China Wants with me, Sam Olsen and of course, Stewart Paterson. Today we are talking about technology again, but specifically around a bit of technology that not many people even know exists, but which is completely vital to our day to day lives - and increasingly so - and that is the Internet of Things (IoT).

To do so, Stewart and I are joined by Charlie Parton, who many of you that listen to this podcast will already know given his commentary on what China is up to around the world. He is officially a Senior Associate Fellow at RUSI, the Royal United Services Institute here in the UK. Charlie spent 22 years of his 37-year diplomatic career working in or on China, Hong Kong and Taiwan, and was actually chosen as the UK Parliament's Foreign Affairs Committee's Special Advisor on China. The reason we have got Charlie on today is to talk about a new paper he has written about the Internet of Things. So welcome, Charlie.

Charlie Parton: Thank you for having me.

SO: Charlie, in a nutshell, tell us about your paper and about the risks it highlights?

CP: Well, it all stemmed from the past when I was looking at the Huawei business, and several of us were deeply opposed to what the British government's policies seemed to be at the time. Eventually, the British government, I think, made a wise decision on that. But then looking around, we could see that governments would tend to play Whack a Mole and say, "we don't like Hikvision", or "we don't like Dahua", or whatever it is, when there are many more serious threats, that perhaps should be counteracted in a more generic fashion.

The most obvious one of those was cellular Internet of Things modules, not a phrase that I have to say I was that familiar with a year ago, but I have certainly become so, and it is not an item that most of our politicians on either side of the Atlantic have ever heard about or ever really considered. And yet, as you said in your introduction, these are increasingly important. They are in so many different uses, whether that is industrialisation, energy, transport, security, point of sale terminals, smart meters, and when you start getting into the home, cars, doorbell cameras, you name it. I mean, they are just enormously important. Perhaps, I should just start by explaining what exactly one of these cellular modules is, that might be helpful, I suspect.

SO: I think so, yes.

CP: In essence, it is a very small piece, only a couple of centimetres squared probably, but very powerful and embedded with sensors, software, antennae, geolocation capability, processors, and it connects to the internet, rather, like your cellular phone does. But it is very useful because when you have systems that you really cannot afford to drop out, like the Wi-Fi dropped out. These do not connect through Wi-Fi, so if you have a multi-million-pound industrial line, which cannot afford a break in production, it will cost you a lot of money, you want to connect through these things.

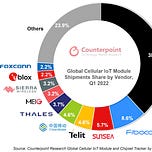

They link up with each other, they pass data to and from so that you can improve your systems, and they have the potential of passing the data back to the people that manufacture them. And therein lies a really big danger. Because increasingly, what the Chinese are doing is trying to ensure that the three companies which produce these cellular modules, the Chinese ones; there are plenty of European American and Japanese and Korean companies that also produce them. But what they want to do is establish, you might say a triopoly, or monopoly on the market. They currently have 54% by sales, 75% by connectivity. And I dare say, very few of your listeners would have heard of the likes of Quectel or Fibocom. They may have heard of China Mobile, which is actually the smallest of three, whereas almost everyone would have heard of Huawei. And yet, I think in the longer term, these cellular modules by these companies are probably as great, if not a greater, threat to our systems and societies.

So again, just if I may very briefly say why it is such a threat. First of all, if you create a dependency by holding a monopoly, and these companies like so many Chinese champions are given very advantageous financing and subsidies and various other methods to ensure that they try to achieve this. But if you achieve that, then we in our countries become dependent upon them. And we have seen what Chinese companies, or the Chinese Communist Party will do when you get a dependency. Just look at what happened during COVID with PPE and other equipment, they will use it for political ends. And so that is one danger, the dependency danger.

Another is the fact that vast amounts of data are going back to China, and you can make some very interesting one might say 'tools' or 'instruments' out of data, and we can discuss how that might be. And thirdly, of course, because the whole point of these things is that data goes in and out and you update the software to improve system or whatever, you could put into them some software, which, again, allows you in effect to do some really disruptive things like mess up a country's grid or bring its traffic to a halt. Again, we can discuss instances of how this might happen. So from those three areas we have got, I think, to be very careful not to allow this quiet plan to proceed unimpeded.

Stewart Paterson: So, Charlie, we have been here before, haven't we, in terms of China cultivating dependencies on new technologies and seeking to establish monopolistic positions. In your view, at the moment with regards to the Internet of Things, is the biggest barrier to concerted action, an economic one in terms of corralling the necessary support to push back against this attempt at creating a dependency? Or is it still a political one in the sense that there is not yet a realisation amongst Western policymakers that China is capable of a sort of malign intent in using this sort of geoeconomic policy to create influence?

CP: Well, much of it, I think, is what you say at the end there. First of all, I think governments - 'free and open countries', if you like, it is a better expression than 'Western' - are beginning to realise that China really is a threat, it really is hostile power, and therefore, we should not allow these dependencies to be created. That is still not necessarily so embedded in our government's mind that it achieves a higher priority than sometimes some of the more immediate gains of let's say a cheaper alternative, and it is cheaper for a reason precisely so that they can get these monopolies. So that is one thing. The other thing is that, as I have gone around talking to governments on both sides of the Atlantic, and indeed, in Brussels, people simply do not know what a cellular IoT module is, they have not heard of it. And again, I will be quite honest and say that back at the start of last year, I did not either. So it is a learning process.

There are other differences. I think that the sorts of instruments that the Americans in particular have been drawing up and using, do not quite apply in the sense that much of what America is doing, if you take the CHIPS Act and semiconductors, is stopping the export of technology to China. But these things, these modules are not actually that high tech for a start. Furthermore, it is not a question of exports, it is the imports of these into our countries that that is the problem. And so, we need to devise ways of ensuring that individuals, companies, governments, defence contractors, whatever, do not put these devices in whatever equipment or processes they have got, because of the dangers that I have outlined.

SO: Okay, Charlie, so what are these dangers? Let's drill down to that, because if we had someone from one of these companies here today, I am sure that they were do exactly what Huawei did when that whole Huawei issue kicked off a few years ago, and say the dangers that you are saying could happen just simply are not true. We are an honourable company with no links to the Chinese Communist Party, and what you are saying in terms of the actual specificities of the backdoors and stuff just is not correct. So tell us, looking at it from a slightly cynical point of view, how would you argue back or push back on someone from these companies, if they challenged you, on your view that there is a danger? And how do you qualify that danger in the first place?

CP: Well as a sort of general comment of course, these companies, I mean, Huawei is a particular one, I think they probably love discussing its ownership, and they say "we are a private company" or whatever. It is entirely irrelevant, in a sense, even the security laws that China has, which oblige companies and individuals to hand over any data requested by the security organisations, you do not need to say, "Oh, well, let's point to those". Because anyone who has spent any time in China knows that if the Chinese Communist Party says to anybody, company or individual "Jump", the only answer is "Certainly, how high?" And so, of course, Huawei and others, if I asked would have to pass over this data. And of course, when you think about Huawei and TikTok and others who solemnly said, whether it is to the American Congress or to our parliament, "no, no, we don't repatriate as it were the data back to China", and then have been caught lying, they do.

Ultimately, it comes down to a matter of trust because these devices are updated on a very frequent basis. That is the whole point, you improve the processes, not just their own functioning, but the processes they control. And so, to devise a piece of software that you could then put in would be a matter of a day's work probably, and trying to find it would be very, very difficult. You can actually egress the data, or you can switch the device off remotely. And I just think that given the nature of the Chinese Communist Party, its control over its companies and individuals, it would be irresponsible of government to allow such weapons to be placed in their hands.

SP: And presumably Charlie, one of the issues here is that the United Kingdom tends to import a lot of these things indirectly, in the sense that they are already embedded in hardware that we import. And so, in a way, it is not our decision, it is further down the supply chain where a decision has to be made to change supplier, cut the Chinese supplier out, and that requires quite a high degree of sort of multilateral cooperation, I would imagine.

CP: Well, and decisions by individual companies. You may have seen on 6 January a report in The i newspaper about the British security authorities worried about data emanating from a government car. They did not give the full details, but it was not just one car, it was many cars, and it was from some quite important people. The car company will have not thought very hard about it, the cellular module will be part of a larger computer component that would have been slotted into the car, and they will be looking at price and performance and not really worrying that it was from China. What we do not know is what exactly turned the British authorities' attention to that particular car, whether it was routine, or whatever. But the point is that, yes, your car has one of these things, and if it is a Quectel module or Fibocom module, then indeed your data can be accessed remotely from China.

I think cars are quite a good example to take, because as you have seen in the papers, some of the comments about this issue in recent days, there has been a lot of sort of jokes "ho ho well my fridge is informing on me, or my doorbell - and isn't that funny?" Well, it is not really very funny. Cars are a good example. If every day your car is registering through its computer, and the cellular module too, that it is parked in, let's say, in a certain place in Cheltenham. Well, yes, you work at NSA. Or if you parked every day in Langley, Virginia, yes, you work for the CIA. And then you start following those cars and being shown exactly where they have gone, et cetera. It is not just individuals, of course, governments buy fleets of cars, and then you have problems there. So now I think we have got to be a lot more knowledgeable, and security conscious. And that, I am afraid, means not having these Chinese said in the modules, but buying from the plenty of other countries, which would be trusted suppliers, because of the risk.

SO: So you say that, but one of the things that we came up with in our recent reports on 1 December on the UK's direct and indirect exposure of its supply chain to China was just how difficult British companies especially, but European companies, more broadly, were finding it to deal with the onshoring and friend-shoring team that has now sort of taken hold of a lot of the industries; in other words, moving manufacturing out of China, and giving the contract to a German company or British company.

First of all, they have not got the supply line capacity, they have not got the people who are properly trained. But also, they have not got actually a lot of the inputs that they need, because those inputs themselves come from China. So my question is, it is all very well us highlighting this as a threat, and the report is very credible in its analysis, but it is the 'what to do' that kind of stumps me, because if China is making huge amounts of the components that are needed for the cellular IoT modules, then how do we actually remove a whole supply chain of those parts out of China? Is there a plan? And if there is not a plan, which country, which government, which department can come up with one to reduce our dependency on China?

CP: Well, yes, I can see that this is of course a really big problem. But first of all, there are plenty of other companies that produce these things, and of course, they have probably been held back by the unfair competition they are receiving. Secondly, and again, this is something that governments, one hopes that GCHQ, or NSA are really taking these things apart, and looking at it, but it is not necessarily the hardware within them that is the problem. It is the software, and I think you have to make sure that it is not software that is coming from these companies - Quectel or Fibocom or China Mobile - but is actually put in by a supplier that you trust.

Of course, if you are saying, "Well, ultimately, if the Chinese really want to mess around, they could withhold some of the other components of these modules." Well, that is true of just about anything in a sense, that is not a problem that is specific to these cellular modules. But if they start doing that, or you fear that they are doing that, then you have to start manufacturing them yourself. But as I say, these are not particularly complex pieces of kit.

SP: It strikes me that this is a very clear cut example of "where there is a will there is a way", because as you rightly pointed out at the beginning, the Chinese have not yet been successful in monopolising this part of the supply chain. Therefore, the door is still open for us to push back and support those companies that are competing with the Chinese, and ensure that the products we buy come from a more immediate supplier. So, in that sense, the report is very timely, because it is not too late, we are not having to start from ground zero. But I think the question I have really is on the broader application of this kind of policy, you mentioned 'Whack a Mole' earlier. It appears to be the case that there is constantly another product coming up in which the Chinese are cultivating a dependency, and we must be alert to it. Where does this sort of responsibility lie within government for spotting these ahead of time? Where is the departmental responsibility?

CP: Well, that is a very good question, and in some of the sort of technical matters, I would imagine that GCHQ is the one that, just as it did with Huawei, when it had the cell looking at the Huawei, so GCHQ should be looking at these sorts of data egress threats. But again, it goes to a much wider problem that I have been talking about for some years now, in that China's intent is to dominate the new sciences and technologies and dominate the new industries from them, because from that, you get economic rents and that leads to being a sustainable superpower and having geopolitical power. Yes, it is developing quite a lot itself, it has considerable powers of innovation, etc. But it is also using other methods to get hold of it, either buying our brains i.e. our start-ups, or hiring them in our universities and getting our professors to do what is really at times highly inappropriate research into things that either help the repressive state or China's military.

SP: What is the answer to all this?

CP: What I have been saying for a long time is that we need a sort of SAGE-type committee that gives a quick answer to companies or to academics that says, "I am sorry, cooperating with China in this, or selling your company or taking Chinese investment into your company in this area is simply not permissible. It is either helping the repressive state or the military and it is a threat to our national security or long term prosperity, or our values." In other cases, "Yes, that is fine. Go ahead, work with the Chinese, they are good. We need to maximise cooperation wherever we can" or "this area, it is a bit grey on balance, we say yes" or "on balance, we say no".

Certainly, that sort of committee is needed now, where it lives in government, or who contributes it is, says he ducking the issue, a matter for government. And you can see that there would be security services input - NSA, Ministry of Defence, Foreign Office to give a political angle, BEIS (Business, Enterprise, Innovation, Science Department) etc. But the expertise would come from those who really understand the technology, giving advice to government in that sort of SAGE-type committee way.

SO: So Charlie, in the last few months, we have seen America really up the ante against China with its announcement of the banning of exporting advanced chips to China. There is obviously a lot of people in America who actively want to curtail and push back on China's influence globally. But we are speaking now in the in the aftermath of the balloon issue, what do you think was going on there? And how is that going to impact China-American relations? Because I am thinking that what you are saying here is just yet another part of the relationship to be sorted out. How much can America rely on China, and if stunts like the balloon thing keep happening, is that just going to increase the antagonism between the two countries and make it even more difficult for America and China to cooperate on anything, let alone on advanced technologies?

CP: Well, I am sad to say, I mean it would be nice if everyone could act in a very mature way and say look we have to differ, and in these areas, we are going to work separately. I always quote the American poet, Robert Frost, "good fences make good neighbours". Indeed, we need those fences, and from those, with those, we can then go out and cooperate with China in areas which are not sensitive. But I do not think we should get too distracted by balloons, it is just one incident. But the underlying truth is, and if you, as you do, read what the Chinese say, I think it is a fair characterisation to say that China's entire foreign policy is based on a deep anti-Americanism, on a systemic competition between their version of systems and ideologies and what they perceive basically to be an American, and then they lump us all in with that.

So I think there are going to be increasingly these incidents. The balloon one, well, it does not seem on the surface from what the Pentagon and others have been saying, that the actual technological threat was that great. But we will see other things. It may well be that in the next year or two, in the Taiwan Straits, an aeroplane will tip another aeroplane as it did in 2001, and then we have an incident there. So I am afraid we are destined for a world in which the 'D word' dominates, whether that is decoupling, de-risking diverging, take your pick. And we would be unwise not to prepare for that, just as the Chinese are. I mean, if you look at their policies of dual-circulation self-sufficiency wherever you can, et cetera. They see it quite clearly, I think we sadly have to recognise it too.

SP: Charlie, thank you very much indeed for joining us today. Quite clearly, I think the Internet of Things, and China's penetration of our communication networks and its ability to harvest data is something that our policymakers need to get on top of as soon as possible, especially since there is a viable alternative at the moment that needs protecting and nurturing. So thank you very much for a very timely report and for joining us on this episode of What China Wants.

CP: Thank you for the opportunity of contributing.

Share this post