Hello and welcome back to What China Wants with Sam Olsen and Stewart Paterson.

Today the Evenstar Institute launches its latest research, measuring and understanding China’s influence in one of the world’s most strategically important regions, Southeast Asia. (A summary of the report can be found here.)

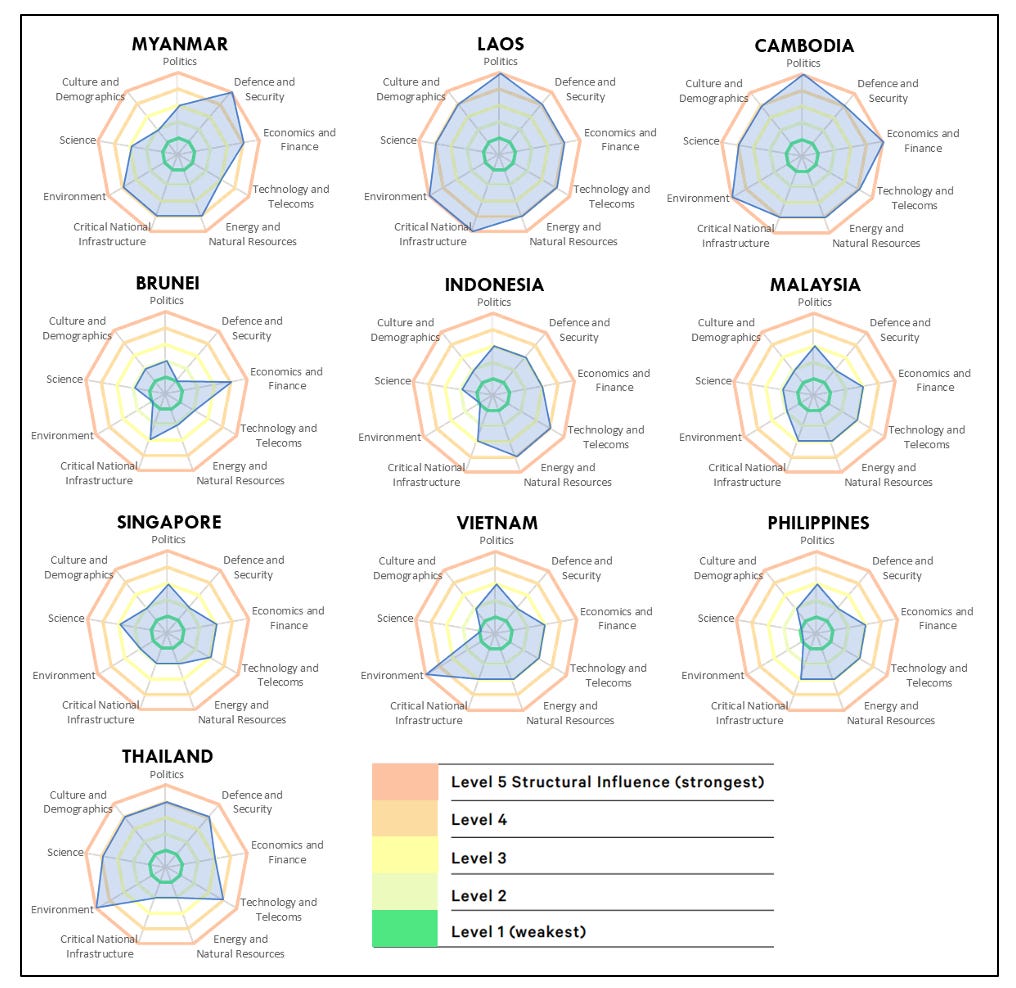

The culmination of six months of research, it is titled Southeast Asia’s Emerging Geopolitical Order: China’s Structural Influence and The Evolving Regional Balance Of Power and looks at the way China’s influence has evolved in the region over the last decade, across multiple domains (including Economics and Finance, Politics, Critical National Infrastructure, and Defence and Security).

The research was carried out using Evenstar’s proprietary data models, analysing hundreds of thousands of data points, together with AI-powered data enrichment from our technology partner Adarga.

In today’s episode Stewart discusses the paper with Sam, the report’s co-author, and Evenstar’s Director of Research Dr William Matthews.

Here is a summary of the main findings:

Southeast Asia is strategically important to the West and its allies, in terms of its commodities, political and defence ties, and location at the heart of the Indo-Pacific.

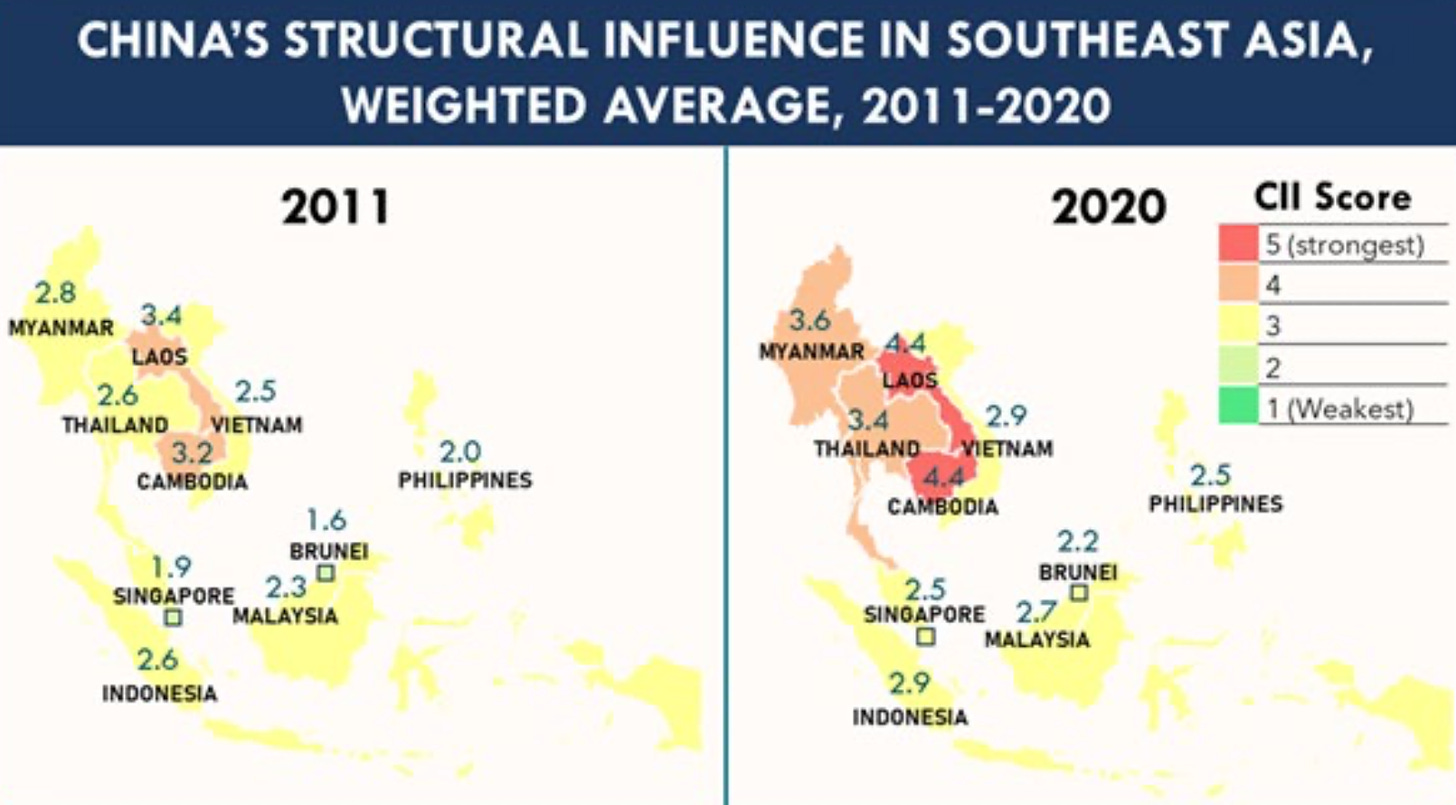

However, China’s influence has increased rapidly over the last decade in every Southeast Asian country assessed. The greatest increases were in Technology and Telecoms, Defence and Security, and Economics and Finance.

China has been able to dominate digital infrastructure in many ASEAN states, allowing it to lock in long-term influence. This extends China’s influence to other areas reliant on digital platforms, such as Defence and Security, and excludes foreign competitors.

China has developed economic ties which allow it to rapidly scale up its influence via investment, elite capture, and dominance of digital infrastructure and critical national infrastructure projects.

China’s highly asymmetric economic relationships with many ASEAN nations enables a high degree of influence across sectors.

China has used the opportunities created by the distancing of the USA following the 2014 coup to rapidly increase its influence in Thailand, and attempt to “flip” a US treaty ally. The diplomatic isolation of Myanmar similarly means it is now highly dependent on China.

Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Vietnam have proven more resilient to China’s influence due to their diverse economic relations, allowing them to better balance engagement with China and the US.

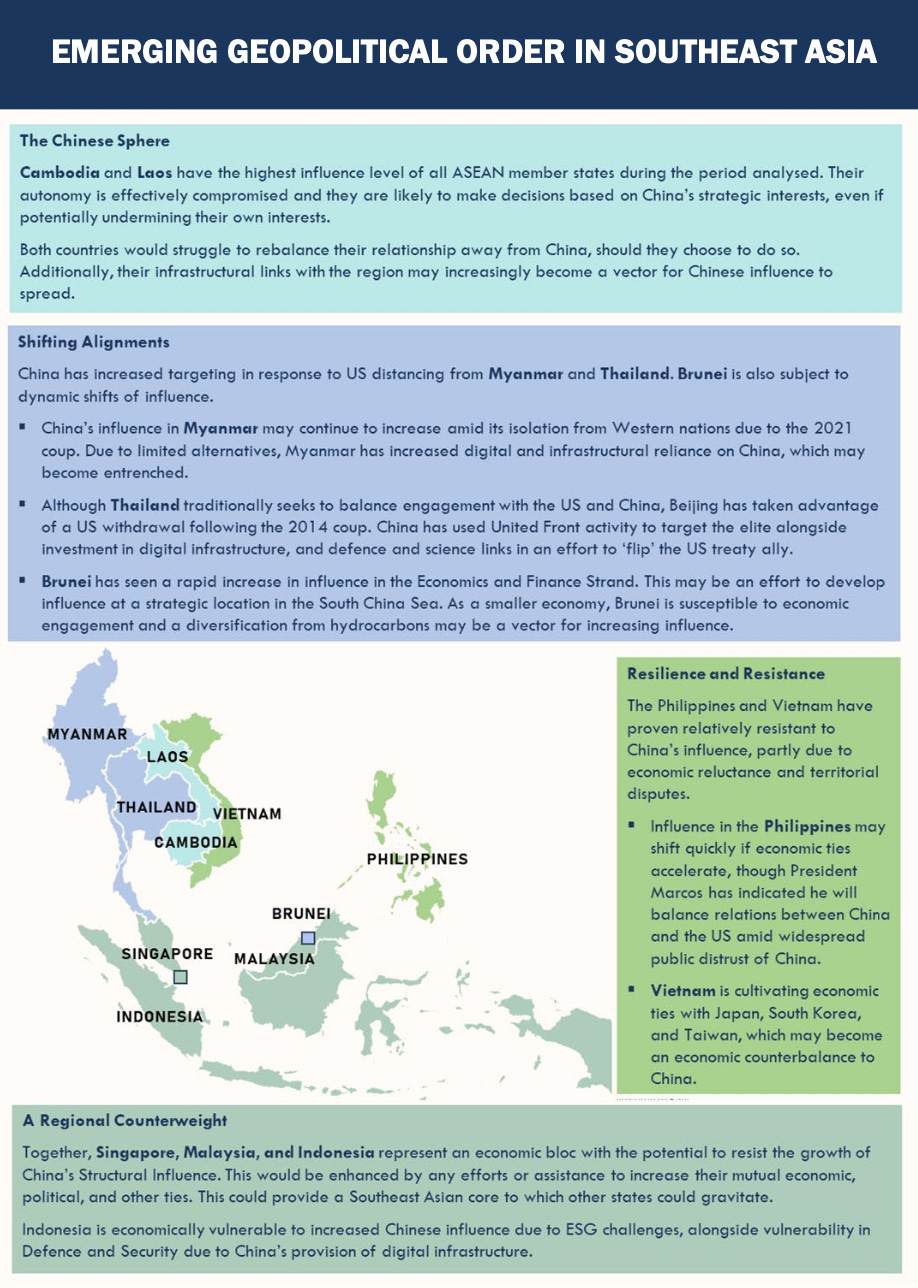

China’s evolving influence is driving the emergence of a new geopolitical order in Southeast Asia, with Cambodia and Laos effectively client states; Brunei, Myanmar, and Thailand susceptible to realignment; the Philippines and Vietnam remaining resistant to China’s influence; and Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore having the potential to act as a regional economic counterweight.

You can also listen to the podcast on Apple, Amazon, or Spotify.

As always please do share, comment, and subscribe. We’ll be back soon with more What China Wants.

Many thanks for listening.

(Note that a summary of the report can be found here. If you would like to receive the full report please email Nick Zambellas nz@evenstarglobal.com)

***

Here is the transcript:

Stewart Paterson: Hello, and welcome to What China Wants, my name is Stewart Paterson. Today, I am joined by two co-founders of the Evenstar Institute think tank, my normal podcast partner Sam Olsen, and Dr. William Matthews, the Director of Research.

We are going to be talking today about China's structural influence in Southeast Asia. Sam, let me come to you first, the Evenstar Institute has this wonderful report out on Chinese structural influence in Southeast Asia. What is structural influence? And why is Southeast Asia important?

Sam Olsen: Well, thanks Stewart, it feels a bit weird being interrogated by you on the other side of the desk. As you know, have been putting together a report on Southeast Asia for the last six months, using the influence models that we have created for the Evenstar Institute, which is the think tank that What China Wants fits into.

Those models came about after many years of analysis as to what actually influence is. We started thinking about this a long time ago, because there did not seem to be a proper analysis undertaken about what China was actually doing in the world. There was lots of conjecture, but there was no real data. So we thought we could put something together in a model, which would be a quantitative basis for understanding exactly what China was doing in Country A, B, or C. And on that we have a qualitative layer as well, which I might add, is powered in part by our technology partner Adarga, the AI platform, who we do a lot of work with. So Adarga has helped us to come up with a lot of the insights into this, as well as our huge quantities of databases of what China is doing across a number of things from trade and investment to academia, to critical national infrastructure ownership, to defence and security etc. All of that is brought together into this report on China's influence in Southeast Asia.

And to your question, why did we look at Southeast Asia? Well, that region is just vital for the whole world. It is big in itself; it is about 680 million people, which is about one and a half times the size of the EU, and double the size of America. But it has also got huge amounts of resources, whether it is fish in the South China Sea, or mineral resources - 12% of the rare earths that we need are processed in Malaysia, for example.

But it is geographically vital as well, because it is the gateway to China and it is the home of many alliances with the UK and the US and Australia and other countries in the West. For example, Thailand and the Philippines are treaty allies of America. Brunei is where a lot of British Army soldiers do their training and we have got strong historical connections there through the Commonwealth, and through increased interaction through the ASEAN dialogue partnership that we have done in recent years. So, the region of Southeast Asia is vital, and it is good to be able to see exactly what China's influence is there, for the West to understand where they stand with regard to their own influence in the region.

SP: William, you are in some ways, the brains behind the methodology and the process of analysing influence. So, if I could come to you and ask, could you just talk our listeners through the way that you approach structural influence and how you set about analysing it?

William Matthews: Sure. Our concept of structural influence essentially refers to the capacity of a country - in this case, China - to bend another country to its will based on its ability to compromise that country's autonomous decision-making. The way that we approach this is to think about nine what we call 'strands', which are basically domains of a country's activity in which China is able to establish influence. So those includes things like economics and finance, politics, defence and security, critical national infrastructure, technology and telecoms, and so on.

The way that we look at this is we draw on our huge quantitative database and those qualitative assessments to basically derive a quantitative metric for influence over each strand. So for that, we will be looking at things for example, in terms of politics, things like number of diplomatic engagements, level of United Front activity in the country, and so on, and thinking about what that means for the targeted country's exposure to Chinese influence, and how asymmetrical the relationship is, and the extent to which that country is dependent on China within that strand. Then we derive scores for the country overall, and that is done basically using a weighting system where we think about how influence in each of those strands is able to compromise that country's overall autonomy. That allows us basically to trace the development of China's influence over time, as well as compare it across countries, which is one of the things that we have done in this report.

SP: And so, Sam, when you look at these various strands, are some of them more important than others? Do some of them lead and others lag? And how can you sort of spot a rising trend of influence, be it from China or any other country for that matter?

SO: The most important thing to understand is that some strands are more important than others. The ones that are most important are those that would bake in the longest term, and the most important influence. That, to be honest, is the economy and politics. But there is another one as well, which is really vital to talk about, which is digital infrastructure. One of the things that came out very vividly in this report is that, of course, China is massively important economically... I mean, China's massively important economically around the world, the largest trade partner with 140 countries, 30%, of global manufacturing, and so on. But within Southeast Asia, it is really pushed out to America as the number one trading partner to quite a degree. And although it's FDI does not fit in as much as America's, the overall economic relationship is stronger with China.

What became more interesting was the spread of Chinese digital infrastructure in the region, which obviously are very closely linked to the economic development. What we mean by digital infrastructure is 5G networks for mobiles, undersea cables for broadband connectivity, space - so for example, using Beidou, which is the Chinese GPS equivalent, rather than GPS, which many countries are doing from everything, from transportation, to agriculture, to security, like facial recognition and smart cities and stuff. All of those things come together under the banner of digital infrastructure.

The reason that that is so important for influence is because once you have spent billions and billions putting it in, it is very difficult, both in terms of actually getting it out of the ground, but also in terms of cost and political will, to replace it. And as China builds out the digital infrastructure - 5G, space, etc - then lots of other things in the modern economy and a modern society fit around that, which gives China a long-term ownership or dominance, at least of many of the aspects of the modern economy.

SP: Thanks Sam. William, when you are looking at Southeast Asia, obviously, our listeners will immediately observe there are some idiosyncratic features of the region that lend themselves to Chinese influence: its geography, the fact that it is on China's doorstep, but also, large ethnically Chinese populations in most of the countries, if not all of them, and particularly the business elites in those countries tend to be of Chinese ethnicity. To what extent is Southeast Asia, in your view, a sort of special case in terms of the degree to which Chinese influence is received, or the ease with which China can penetrate?

WM: That is an interesting question. There are two dimensions there that link into that which I think do make Southeast Asia a special case. One is something that is reflected in the patterns of influence that we have noted in the report, is that China's influence tends to be greater on mainland Southeast Asia than maritime Southeast Asia. In part, this is due precisely to issues of geographic proximity, including, for example, China's effective control over the Mekong River through dams. This gives it a high degree of potential influence over the five states downstream - Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Thailand, and Myanmar - simply because China then has the potential, the capacity to influence things like water supply. But this also includes things like, overland access into China and from China and so on.

In terms of the region's ethnic Chinese population, this is absolutely something that Beijing targets through the activity of its United Front Working Group. What the United Front Working Group attempts to do is essentially target ethnic Chinese business elites in the region, with a view to trying to get them to reorient more in line with their interests than in the interests of their own countries. Now this is not always successful, it is much more successful in cases where you have ethnically Chinese business elites who are relatively recent migrants from the People's Republic of China. Beijing has been less successful in cultivating it where you have sort of older ethnic Chinese populations who do not necessarily feel particularly sort of warmly towards the People's Republic.

But in some countries, this has been particularly effective. Thailand is an interesting case where there is a United Front sort of penetration at very high levels of the economic and political elite in the country, to a point where that is having an impact on the internal debate in Thailand as to where the country should be orienting itself between China and the West. However, you know, it is important to note that also, we see other countries like Vietnam, which have taken a very active stance against allowing any kind of activity like that to operate in the country. So it can be a very important vector for China's influence, but it depends a lot on the sort of response of the country being targeted.

SP: That is really interesting, and let's come on to Thailand in a moment, because obviously, clearly, it is a very important sort of 'swing state' in the region. But Sam, one of the conclusions of the report is that Laos and Cambodia are effectively client states, although you do not go quite that far necessarily in labelling them as such. But perhaps you could just talk us through how that has happened and how deep China's influence over those two countries is?

SO: Yes, so Laos and Cambodia have over the last 10 years, gone from being autonomous in their decision-making for the majority to being very heavily dependent on China. China's influence is economic, so huge amounts of the FDI and trade that both countries have with the rest of the world is actually with China. For example, in Cambodia, a large part of the roads and the infrastructure has been built by China and in Laos too, the high-speed railway has been built by China, and the dams that now provide 80% of the export earnings for Laos through the electricity they generate, that was all built by China as well. Not only economically is China dominant, but militarily, they provide a lot of the weaponry now. Politically, there are huge connections between Laos and Cambodia and China. And of course, as William said, there is a reliance on the Mekong River, which China can now basically cut off because of its 11 upstream dams.

For those two countries, their autonomy is determined by China. A good example of that would be in 2019, when Cambodia was asked, or in fact ordered, by China to stop online gambling, which huge numbers - about 700,000 we think - of Chinese people had moved into Cambodia in recent years to indulge in. That was providing an enormous amount of tax take to the Cambodian government, which is one of the poorest countries in Asia. China told them to switch off their online gambling, which they did, obviously depriving them of quite a lot of tax revenue. But we know that Cambodia really does not have a leg to stand on when it wants to stand up to China, simply because of the economic impact that China can have on the country. And just a final stat on that is that two thirds of Cambodia's exports come from garments, but two thirds of the inputs into the garment industry come from China. So, just like Laos is dependent on the water from China for its exports, Cambodia is dependent on China for the inputs into its main export as well.

But I want to just build on something that William was saying a second ago about the United Front. The United Front are also very active in those two countries. We know this because the United Front actually publicise an awful lot of what they are doing online in Chinese, which we read and monitor. And another country which we will talk about in a second for sure, is Brunei, where the United Front have been very active too.

SP: So William, our listeners probably thinking, "Well, hold on, isn't it quite natural that China should have a significant amount of influence in these countries, given its size, and the relative size of itself vis-a-vis the Southeast Asian nations?" I suppose the question is really, to what extent is structural influence something that just 'happens' naturally through international relations between two countries? And to what extent is it cultivated? And to what extent can these Southeast Asians countries enjoy some sort of agency themselves over the level of influence that outside powers gather in their societies?

WM: Sure. So obviously, part of it naturally occurs. China is a huge economic power right next to Southeast Asia, so of course, it is going to have, you know, one would expect it to have major influence in the countries of Southeast Asia. To a significant extent that is inevitable, if you like. There are other dimensions like we have been talking about with the United Front activity, which are sort of wholly targeted and deliberate cultivation. I think, even though in terms of things like China's economic relationship with the region, we do see though, that there are patterns of activity there where China is clearly seeking to - it is hard to know whether or not the deliberate intent is to create structural influence, or however they sort of conceive of it.

WM: But there is definite deliberate targeting of certain areas and sectors with a view to advancing China's interests. This includes, for example, investing in things like critical strategic resource production, things like that, and things like digital infrastructure. Digital infrastructure does seem to be part of something which is a much more sort of deliberate attempt to cultivate influence. That relates to things like China's pushing of a setting of Chinese technical standards and using those as a basis for things like digital infrastructure, critical national infrastructure development. And those are things which have the potential to lock-in China's influence through things like the need for continued maintenance, upgrades, and so on - like Sam talked about earlier, the difficulty in switching to alternatives.

But of course, these countries all have agency themselves. We have identified in in the report sort of various ways in which countries do push back or are able to resist China's influence. In some cases, these come from sort of just the country's existing sort of economic situation. Indonesia, for example, as the largest economy in Southeast Asia, is also the sort of the country in Southeast Asia which really has a very diverse economy, and relies on a very wide range of trade partners and so on. That that kind of diversification of economic ties correlates with a lower degree of China's ability to cultivate influence. Vietnam is another good example in that Vietnam has cultivated closer economic ties with Japan and South Korea. That also means that it is then inevitably less dependent on China.

SO: William, can I just come in there, because I think it is important to talk about this agency. Some of the critics of China's influence and some of their critics of America's influence in the region and in fact, the world, say that by discussing things from a point of view of China or America, you are removing agency from the countries affected. I think that it is really important to note that in our research for Southeast Asia, one of the things that comes across very well, is the fact that these countries do have agency, massive agency in fact, and right up until the point where they end up in China's orbit, in which case their autonomy is somewhat reduced.

That is especially the case for Laos and Cambodia. But how did Laos and Cambodia get there? Well, they made decisions, which were either for the best of the country, or because of elite capture, which ended up resulting in those two countries having such great ties to China that they cannot really operate without them. The United Front does help to encourage the decision-making which might not necessarily be in the best interests of that country. But it is a decision made, and that is a reflection of the agency.

And just getting back to Brunei, I think one of the things that we have noticed is that whilst Brunei retains a very strong close connection with the UK and the West over its military side - as I mentioned, the British have got a base there. One of the things that has become clear in the last few years is that the economic side of Brunei's relationship with the outside world has been completely dominated by China. They have built a new refinery there, PNB refinery, which is absolutely massive, to the extent that our analysis shows it is likely this will completely change the pattern of Brunei's economic engagement with the rest of the world simply because China now dominates the natural resources, which in turn dominates the exports of Brunei. And the United Front actually publicise the fact that the United Front people working on that refinery, the ones that helped to get it built, were given a public award by the United Front to reflect their service to China. So yes, there is agency but this agency within these countries is being helped along by Chinese efforts, at the obvious level and at the perhaps less obvious level as well.

SP: And Sam actually, maybe that is a point we ought to mention here. Is there a big difference in the level of Chinese influence between the democratic states within the ASEAN bloc, and the non-democratic states within the ASEAN bloc?

SO: Great question, Stewart, William what are your thoughts on this?

WM: I think we do see some differences there, but I would also caution against thinking that there is necessarily a clear-cut line. So, for example, two countries that we focus on in the report as being notably resilient to China's influence are the Philippines on the one hand, and Vietnam on the other. Now in the case of Vietnam, a lot of that resistance to China's influence comes from a long-standing history of difficult relations between the two countries.

In the case of the Philippines though, the Philippines being democratic has had an impact. We see across many countries in Southeast Asia, not necessarily a particularly favourable public opinion of China, and its actions in Southeast Asia. Now in a country like the Philippines, where there is a high level of civic engagement, that has an effect, because it means even when the Philippines was under Duterte, for example, Duterte tried to cultivate most closer ties with China. But in a context where you also have high levels of popular political engagement and an unfavourable opinion of China's activities, that is inevitably something that elected leaders are going to have to take into account, and which will therefore impact on the capacity of that country to counter China's influence and potentially hinder the ability of China to establish that influence in the first place.

SP: Sam, let's talk about Thailand, because obviously Thailand was a democracy, then we had the military coup, and in many ways, it is kind of pivotal to the region, isn't it? Which way Thailand goes or what balance Thailand chooses to strike, will have quite a broad ramification for the whole of ASEAN won't it?

SO: Yes, Thailand is one of the most important countries in Southeast Asia and Asia as a whole. It has got a large population, it has got a thriving economy, which is vital to the international supply chain for its factories, and its components, etc. And geographically, it is very importantly situated at the heart of Southeast Asia mainland. And so whatever Thailand does is going to have an impact on the region and on the continents as a whole.

Since basically, the Cold War, America and Thailand have been very close. Thailand is one of the few treaty allies of America, and it is a country that has received huge amounts of international Western support and investment. But in 2014 there was a coup, a military junta took over. Because of that, the Americans decided to pull some of their support for Thailand, which included stopping for example, the young officers going to West Point Military Academy in America. There was an awful lot of anger by the military junta, and they felt betrayed by the Americans, and since then, China and Thailand have become a lot closer.

We see that in a number of ways. First of all, trade continues to increase. China is building Thailand's digital infrastructure. China and Thailand are creating a very strong scientific relationship. For example, China recently gave Thailand one of its own nuclear fusion reactors as an experiment, and set up a think tank there on science and technology. But also they have become very close in terms of military engagement. Thailand is one of the only countries in Southeast Asia, which has actively increased at a significant level its arms from China. It has also done an awful lot of joint exercises with China too. That is not to say that they are not still doing joint exercises with America, they are. But the fact that they do them with China as well is problematic for Washington.

What this means is that China's influence in Thailand is increasing rapidly, and has done over the last sort of nine years. Now, if China does manage to get Thailand to flip away from being an ally of America to be an ally of China, then that would cause a very big headache for America in Southeast Asia.

SP: Sam, obviously, there is a huge amount of detail in this report, and we have only really scratched the surface in this discussion. If our listeners want to get a hold of the report, where can they get a hold of it?

SO: Well, it is going to be published on our website, which is evenstarinstitute.com. But, if you are a member of the What China Wants community, we will also send you a copy in the newsletter there very soon. But in summary, I think this is just a fantastic opportunity to show off our influence models and to show how powerful they are, and how broad ranging they are as well. And so, you will be looking forward to talking to us soon about some other research we are doing in different parts of the world on China's influence and how that compares to the influence of other countries like America, the UK, and potentially India as well.

SP: William Matthews and Sam Olsen, thanks very much indeed.

SO: Thanks Stewart.

WM: Thanks

***

About The Evenstar Institute

The Evenstar Institute is a non-partisan, not-for-profit think tank focused on measuring and understanding the evolving nature of national influence in the twenty first century.

Our current core programmes are the China Influence Index, and Macro Supply Chain: Risks, Challenges, and Opportunities.

For more information on our research, methodology, and proprietary models, please contact Sam Olsen, CEO and Co-Founder, at sam.olsen@evenstarglobal.com

About Adarga

Adarga is an AI software company that specialises in information intelligence. Adarga’s AI platform is used by the Evenstar Institute’s specialist team to enrich their research and enable better, faster and more robust analysis from deeper, wider and broader sources.

Adarga is helping organisations in defence, national security and the commercial sector to more rapidly identify threat and opportunity signals buried within huge volumes of information. By leveraging the power of Adarga’s Knowledge Platform users can accelerate and enrich reporting, rapidly understand intricate networks and perform complex situational analysis in order to mitigate risk, act at speed and gain a competitive edge.

To find out how your organisation can augment its information analysis capabilities and more effectively derive critical insight from in-house and open-source data, please contact

Mike Hepburn at hello@adarga.ai

Share this post