Hello and welcome back to What China Wants. Today we are talking about China’s overseas development aid, and what this means for both Beijing’s influence and the world in general.

A lot of print is dedicated to discussing China’s overseas aid, some very anti (“they’re creating debt traps”), some very pro (“China is just giving the world what it needs”). What is often lacking from these conversations is any data - until now.

In today’s episode we interview Rebecca Ray, a Senior Academic Researcher at the Boston University Global Development Policy Center, which has published a fascinating dataset outlining what China is doing with its aid programme.

Here is a summary of our discussion:

China’s overseas development financing has fallen off a cliff in recent years, down to $10 bn. This coincides with COVID.

Overseas aid is now really a small part of China’s international balance sheet, with the majority of foreign spending being bank lending and FDI.

An interesting finding from the research is that most countries that receive aid from China also receive aid from the World Bank, but the funds received go to different types of project. World Bank and Chinese lending is not so far apart.

World Bank projects tend to take longer to approve, and so the speed of China’s aid decision making is an advantage for countries that want quick investment wins.

Its pattern of overseas financing has changed too, with bilateral mass loans (e.g. giving a bucket of money to Country X for them to do with as they please) has been replaced with small, direct projects (such as a certain bridge or road).

As China reopens to the world, and their economy gets back on track, are they going to prioritise domestic spending or overseas aid?

If Rebecca was going to advise President Biden on how the US can be more successful in pushing back on the influence Chinese aid brings, she would tell him to be more aware of what these countries actually want: need infrastructure, they need connectivity, and they need investment.

You can also listen to the podcast on Apple, Amazon, or Spotify.

As always please do share, comment, and subscribe. We’ll be back soon with more What China Wants.

Many thanks for listening.

(In the meantime, if you would like more information about the Evenstar Institute and our research, then please email me sam.olsen@evenstarglobal.com)

***

Here is the transcript:

Sam Olsen: Hello, and welcome back to What China Wants with Stewart Paterson and me, Sam Olsen. You will have seen if you have any interest in China whatsoever, that over the last few years, there have been accusations and promulgations of China's largesse around the world in terms of investments, sure, but also in giving lots of loans to countries, especially in the developing world. And that has led to accusations, again especially amongst Western commentators, of phenomenon like debt trap diplomacy. But on the other side, people who are more fond of what China is doing, say that this is delivering a public good through the loans, which are not provided by other organisations. And so the question is, is what China is doing in terms of these loans good for the world? Or is there actually another side that needs to be explored?

But before we have any of those conclusions, it is really important to get the data. Thankfully, we do have the data now, and that has been produced by a unit of Boston University called the China Overseas Development Database. We are lucky enough today to be joined by the person who produces that database. Rebecca Ray, welcome, Rebecca.

Rebecca Ray: Well, thank you so much for having me. Great to talk to all of you.

SO: So Becky, you hold a PhD in economics, and you are the Senior Academic Researcher at the Boston University Global Development Policy Centre? That's right, yes?

RR: Yes, that is correct.

Sam Olsen: And how long have you been doing that for?

RR: I have been focusing on China, and specifically to give you a little background on myself, focusing on China's role in Latin America, in particular, for about 10 years now, at BU at what we call the GDP centre. It really sprang out of our Global Economic Governance Initiative that focuses on multilateral efforts for our global goals that we have all agreed to; whether it is mitigating climate change, whether it is the Sustainable Development Goals, financial stability, how are our multilateral and international cooperation efforts getting us towards those goals?

So about 10 years ago, we realised China is the story in development, finance in the world. And at that point, I was just a Latin America expert. And so China was the story, specifically in South America. So we spun off our own separate initiative, the Global China Initiative within the GDP centre, just to focus on how China changes the landscape of what is available in development finance, in investment and trade, and how that changes the prospects for global development in general. So that is where I am coming from, as someone who cares deeply about our consensus goals, whether it is climate change mitigation, and adaptation, whether it is ending food insecurity, or having a better-connected world, and interested in how the global development finance landscape has changed or altered for the better or the worse, or both, by China.

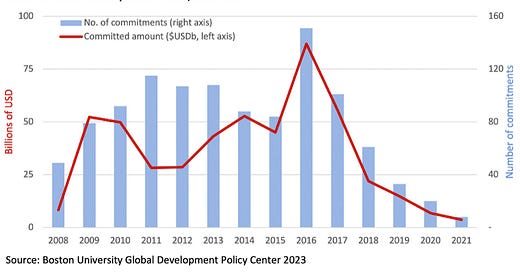

SO: Good. Okay, so you just released your latest iteration of research. But could you just set the scene for the listeners in terms of the size of Chinese overseas development finance, and especially its trajectory in the years covered, the last 13 or 14 years, because I think there are some quite surprising findings in terms of its trajectory, right?

RR: Sure. So, our database covers starting from the last global business cycle peak in 2008, our first edition of it came out covering through 2019. When we put that out, we did not realise that 2019 was also going to be a business cycle peak, and that was our first edition of it. And now we have been able to update it through 2021. To give you an overview of the whole time period, in that time, China's two development finance institutions, the China Development Bank, and the Export Import Bank of China, these two banks, have issued about USD 500 billion in sovereign finance commitments. And to put that in context, that is about 83% of what the World Bank has committed to governments around the world in the same time period. So here we have one country that is doing the same amount, almost, at least in the same echelon as the preeminent global development finance institution that we are all members of. So it absolutely merits understanding what gaps it is filling, what particular risks and cautions need to be applied, and how best it can help us get to our goals.

Stewart Paterson: Maybe I could just come in there because clearly those are the two leading Chinese development banks, but there has been considerable overseas lending obviously by other state-owned Chinese banks or state-controlled banks, such as the Big Four commercial banks, for example. So, your database specifically only covers the two leading banks, is that correct?

RR: Exactly. Our goal is to be comparable to World Bank data or regional MDB data like the African Development Bank, the Asian Development Bank, or the EBRD, or national development banks in Europe, right, KFW or AFD. How does it compare? How does it contrast? How does it add to what is globally available in development finance?

While there are state-owned commercial banks, ICBC for example, they are hugely important but they are not development finance, they do not lend for policy aims. We do not look to them for the climate finance that the world needs, we do not look to them to lay the groundwork for investment that is necessary, but that cannot happen until a certain level of infrastructure or a connectivity is established.

Development Finance are first movers, before private industry has an incentive to move into a place. They are first movers for necessary investments that are cost-prohibitive for that first mover like green energy often has a high cost upfront, but pays for itself in the long term. Development finance steps in when there are projects that are absolutely necessary, but that one company cannot capture all the benefits of and so the private sector does not have an incentive to be active in that area. Here I am thinking of public infrastructure projects that need to be accessible to everyone, like water and wastewater projects. The private sector does not step up to fill those spaces, because one company is not going to capture all the benefits.

So, development finance serves this purpose of creating public goods that serve broader public goals. Where one firm is not going to capture all the benefits, we all agree that we need these things and so let's publicly finance them. That is what development finance does, and so we create this database to compare how China approaches that space, in comparison to all of the many other DFI's that exist in the world. Now, these DFI's are members of the International Development Finance Club, which is a group of DFI's around the world; they meet every year for the Finance and Common Summit, and they have goals for green lending, for example. So it is important to understand what everybody is doing in this space.

We do not think about all of Chinese overseas economic engagement through this particular dataset. It is meant for comparison to other DFI's. But we have other data sets that serve other purposes. We have a Chinese Loans to Africa dataset that looks at those commercial loans, as well. We have a Global Power database that also includes direct investment. But this database is just to think, "how does this change our understanding of what is out there for development finance?"

SP: And when people think of development finance, they usually think that there is a concessional dimension to the development finance, that it is not a sort of commercial transaction, or at least not a purely commercial transaction. And some of the multilateral organisations actually sort of weight their lending according to the concessionality that is embedded in it. Is that possible with the Chinese development banks or are they slightly different in that regard?

RR: That is not possible for most national development banks, Chinese or others, actually. So that is an OECD definition, and the OECD members will use that definition in their own development banks and in their own reporting. And that is great for OECD members, but it is not a broadly-held definition beyond the OECD. And so, when we look at other countries' development lending, it might use instead simply which institution is this going through, and that is the way that works with Chinese development finance.

So there are three major Chinese development finance institutions. The third one that we do not cover is the Agricultural Bank of China, which does not really operate overseas, and so we do not include it. These three have development mandates: Export Import Bank of China, or 'Chexim' as we kind of casually referred to it, is where all the concessional lending goes through. Notably, however, the China Development Bank is a member of the International Development Finance Club and calls itself the world's largest development finance institution. They both have mandates to further development policy or to lend for projects that further development policy, and so we include all lending that comes through these two institutions, in the same way that the World Bank, for example, counts all of its lending as development finance, whether it is going through the IBRD or the IDA. The IDA concessional finance for low-income countries, the IBRD, non-concessional finance for middle-income countries, it is all development finance through the World Bank.

The OECD has its rules about concessionality, and that is wonderful and we would love to have that kind of transparency for national development banks around the world. But it does not exist, and so we use this World Bank-centric approach, that we are all members of the World Bank, so we can rely on those definitions and say, "You know what we can do? We can very clearly say these two institutions exist for development goals. Let's see what they're doing and how well they are doing compared to their peers."

SO: Can I just ask, if this is all about development financing, then surely, the last few years would have been very good for development financing opportunities, since we have all had such a big shock from COVID and the Ukrainian war etc. But your data seems to show that there has been a massive slump in Chinese outward-bound development financing. So what is going on? Why has China not taken advantage of this international situation to push its development finance, and obviously its influence thereby?

RR: Sure, so here is one of the situations in which multilateral development banks have a big advantage, because they do not have a domestic economy to worry about. So here we see multilateral development banks like the World Bank continuing to increase the finance that they can make available, because the need was so great. China, on the other hand, faces its own internal issues as well, of course, and here, I want to talk about maybe a supply side and maybe a demand side, if we can think about it that way.

On the supply side, where do those dollars come from that China lends out? One of the main places that those dollars come from is their current account surplus. Those are the dollars flowing into China's economy from exports, minus imports, as well as remissions and other forms of flows that are similar. That fell by 90% between 2015 and 2018. It went from about USD 300 billion a year to about USD 28 billion dollars a year in that time period. So, the flow of dollars with which China could work really dried up. And during those same years, of course, these were the years when US President Trump and Xi Jinping had that trade dispute, and you really see trade beginning to have those frictions, fewer export dollars flowing into China, less that they can mobilise.

Of course, during those peak years, China is also sitting on a mountain of US Treasury bonds that are earning historically low interest rates, essentially collecting dust. Why not leverage those reserves, and lend them out during a time when global interest rates are so low that from a borrowing country's perspective, it makes sense to borrow? That has not been the case in the last few years, especially in 2021 and 2022, we start seeing currency market fluctuations, rising global interest rates, it does not make as much sense to borrow.

At the same time, China's supply of dollars really is not what it used to be. Now, China's current account surplus has rebounded significantly just in the last year or two. But of course, that has coincided with COVID, and they have their own domestic spending priorities right now. We will have to see if those things align as China reopens. And that is what I will be looking at, to see as China reopens, do they have an interest in pushing that money out the door? Or are they still needing to use it to help smooth out the reopening and their property sector, for example, domestically?

SP: That is really interesting, Becky, because you are absolutely right about the shrinkage in the current account. But 2018 was quite an abnormally low level at the USD 28 billion, and it bounced back to sort of USD 1 trillion dollars in 2019, and the best part of USD 2.5 trillion in 2020. And so, we are left with this situation where and of course, those numbers are augmented by capital inflows, right. So as the domestic capital markets opened up in China a bit more. China was able to induce foreigners to invest, which augmented the dollar availability for the Chinese to recycle out.

And what is quite noticeable, I think is, clearly, China's international balance sheet shape has changed very dramatically. Foreign exchange reserves are no longer predominant, international bank lending has taken a large share of it, along with FDI. But the overseas development finance side of it seems to have shrunk to a very, very small proportion. I think one of your key findings is that we are looking at about USD 10 billion of overseas financing. I cannot remember which two years that was for?

RR: 2020, and 2021 - so the two most intensive COVID years really bottomed out to these very low levels, as you said.

SP: But also, those were years of big capital inflows from markets and large current account surpluses. So you know, in fact, the best part of maybe USD 2 trillion was available to them to dispense. One of the things you seem to be saying, is that it is too soon to say?

RR: I do think it is too soon to say. There is another element too though that we have not mentioned, and that is part of development finance lays the groundwork for the private sector to have the incentive to invest. Right, a certain amount of infrastructure connectivity has to be there in order for it to make sense to invest. And we are now seeing Chinese firms having the experience in a variety of host countries to be able to invest directly more easily. I will give you an example. The East African crude oil pipeline, major investor is CNOOC, the China National overseas oil firm. It is I think, a 35% owner in that project. Now this is an oil pipeline project akin to the ones that China has financed for sovereign governments around the world. But at this point, CNOOC has been in Africa long enough it can just invest directly. There is no need for sovereign finance to go along with it. There is no need for countries to take on the debt. There is no need for concerns about corruption, about what is happening to the money, it can simply be an FDI project, because China has been there long enough to have that experience.

So, it does not necessarily signal an end to Chinese overseas engagement, but rather a maturing of the economic relationship, which is not really surprising. I, as an economist would expect to see sovereign finance for particular contracts, turn into mergers and acquisitions, or minority stakes and joint ventures where a Chinese firm may take on some of the business risk in the long term, but does not really need to have the understanding necessary to establish a company from the start, and then eventually mature into greenfield investment where the Chinese firm needs to understand the regulatory environment etc. to start something from scratch. So it is not surprising to me to see this transition of JV's with minority stakes from Chinese companies, as they are willing to take that risk. It might be less risky financially to have that equity stake, than to have debt, which a country may or may not be able to pay back, depending on what happens to currency markets, interest rates, etc.

SP: Yes, I mean that all makes perfect sense in terms of a sort of debt-for-equity swap going on with China's capital. But your specific database is obviously very much focused on the environmental impact, isn't it? And perhaps you would just like to tell our listeners a little bit about how you are measuring that, and what your observations are about Chinese development finance, when juxtaposed alongside Western institutions development finance, into how it is impacting the key areas that concern you?

RR: Sure, well because we have a precisely geo-located dataset, users can use it for all kinds of things. They can look at corruption, where the money is going; they can look at potential impacts with conflicts. What we look at it with is environmentally and socially sensitive territory globally, certain risk factors that have global definitions, so they mean exactly the same thing in Ecuador, as they do in Angola. There are three of those that are pretty widely used by analysts to look at general environmental and social risk factors. They do not cover all kinds of risks. But like I said, they are globally harmonised, so they mean the same thing everywhere and we can compare across contexts.

Those three are 'national protected areas', that is pretty straightforward; 'indigenous and tribal peoples' lands'; and 'critical habitats for biodiversity conservation'. These vary dramatically in the amount of kind of legal protection that host countries give them, but they occupy about the same percentage of the world's land. It is really interesting that Chinese money is going much more into the lands that are not legally protected - critical habitats - much more into critical habitats, than they are into protected areas, which of course, have host country regulations on them.

So, what does this tell us? This tells us that host countries do not need to be afraid of putting on their own environmental and social regulations scaring off any foreign capital. Sometimes the Western media has an idea that environmental and social protections will scare off foreign investors. But we do not really see that here, we see China money simply going into areas that are where the host country prioritises it. If the host country protects an area, the money is less likely to go into that area. If it is critical habitats, but it is not legally protected, it is more likely to get that Chinese money. So, it is up to host countries to set their own standards and to enforce their own standards, because that is how development finance works. Countries develop an idea, they develop a proposal, and then they take it to the bank, they shop around, they say "who wants to finance this project?" China is not imposing ideas on countries; they are taking applications, just like any other development finance outfit.

SO: So one of the things that you say in your findings is that there has been a change in the sector focus, and it is moving from extraction and pipelines towards transport and power. And so, one of the things setting the agenda for what we are trying to find out in What China Wants generally is looking at China's influence around the world. If you take that change in sectoral focus, first of all, why is that happening? And secondly, how does that impact China's influence, are the two things connected?

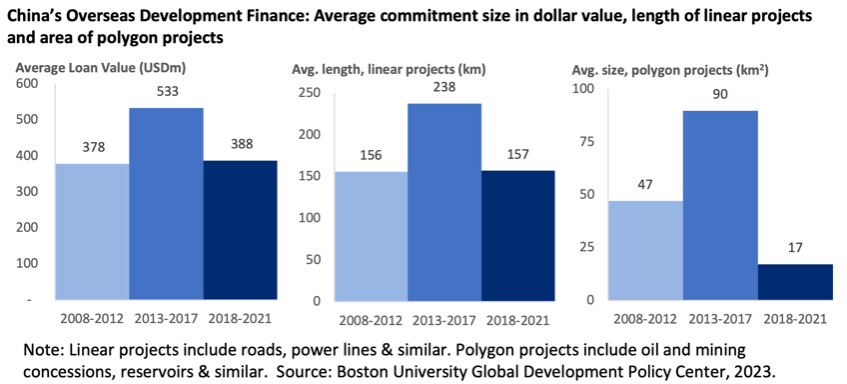

RR: So, let me start with the first point. As China's supply of dollars dwindled dramatically and their overseas development finance shrank so dramatically in those years between 2015 and 2018, after which it has basically stayed low. During those years, we see Chinese development finance really start to prioritise particular projects that they want to support, not just giving general purpose support. And so, if you think of the world's top five state-owned oil and gas companies that used to borrow from China; we are talking about Russia's Rosneft for example, Angola's Sonangol, and three state-owned oil companies in South America - in Brazil, Venezuela, Ecuador. These five companies together would be the top borrower from these development finance institutions in China if they were one country. So if these five firms were a country, they would borrow more than anybody else. But they have not had general purpose support from China since those boom years.

So, China is moving away from this kind of general purpose support for other state-owned enterprises, state to state financing this way. They do not do that anymore. Now they are funding target-specific projects, maybe a road, a railway, a dam, rather than "Venezuela, here's USD 5 billion, do with it as you will". And so this prioritisation of smaller, more targeted support for particular projects is part of what we hear from China analysts and from Western analysts who study China, they call it a "small is beautiful" framework, that we are going to pick out specific projects that we think are most likely to succeed, where our money is going to get the most utility, and stop pouring money into countries like Venezuela where they are not getting paid back., and the money is not going to anything particularly tangible.

As someone who thinks about sustainable development in the global development finance world, this is a good thing when it comes to better targeting the money towards projects that are actually building up public assets, public goods. However, of course, as the world faces climate change, we are going to need large projects that are also well-targeted. So the question in my mind is, "can China keep the beautiful part?" If it is someday not small, can it keep the beautiful part? Can it stay targeted towards environmentally and socially well-targeted projects, if it scales back up, again? Because regardless of where the money is coming from, the world is facing climate change and we are going to need big projects done well, in order to have just and inclusive and sustainable energy transitions around the world.

SO: Stewart, can I just bring you in on this because we are obviously fascinated on Chinese influence, and climate change is incredibly important. But it is difficult to see how China would want to break the habit of a lifetime and invest in climate change projects or any type of project without some kind of payback. But Stewart, just listening to what Becky is saying there, do you think that there is a change in mindset about the use of this development finance in the way that they try and spread their influence? Is there anything in the data that springs out to you as effective of a change in mindset? Or do you think it is the reasons that Becky is saying about the fact that they want to get the money back for a start as being more important?

SP: Well, I wonder if Becky hasn't hit the nail on the head when she was talking about the decline in development finance overall coming from China, and its shrinking proportion of overall capital exports from China, and the diminution in the amount of money going to state-owned oil companies and hydrocarbon projects generally, from the overseas development finance portion. What would be interesting to know is how much of that shortfall or fall in investment has been offset by FDI, or commercial bank lending to equally sensitive, potentially detrimental to the environment, projects, and so the funding has just come from other sources, for example. Because of course, what Becky's database here is tracking is very much just the development finance portion, which, as we have already ascertained, is a very small part of the capital outflows.

But I think when we look at the country breakdown, Becky has got some very interesting observations about that in terms of the bifurcation or not of the global economy along political alignment. Because I think I am right in saying, Becky, that one of your findings is actually that the vast majority of countries by number, actually are taking development financing, both from Western multilateral organisations, and from China in relatively equal portions. Is that correct?

RR: Absolutely. This is a story about finance ministries around the world with a portfolio of projects saying, "Who do we want to take each of these projects to?" World Bank, you are a shoo-in to say yes to a health or education project. You are going to say yes quickly, we are going to get that money quickly. Let's give you the health and education projects. But the World Bank may take two years to say yes to this road project, and we may have a change in government within the next two years, and our whole project portfolio is going to get thrown up in the air. Let's take that to China, because they will say yes next week.

To borrow a phrase from my friend and colleague Chris Humphrey in the UK, we see countries essentially "shopping for development", taking their shopping lists to different DFI's for different purposes. So while Western observers like to sometimes couch this in terms of a competition, I see no evidence for that, from the perspective of the borrowing countries who essentially want lending for health education and highways. And so, they are simply taking each of those projects to whoever will give them the fastest and best deal on those projects. Of course, as I am speaking to colleagues in the UK - of course, you know better than anybody how government spending priorities can shift with shifting executive branch personnel. And so, finance ministries have an incentive to push whoever the head of the executive branch, Prime Minister or President, whatever their priorities are, as quickly as possible through that process.

Now, from a sustainable development perspective, we might say, "You know what, we want this dam to last 100 years, maybe we should give it two years to make sure we are doing it right?" But that is not the political reality of how finance ministries get their infrastructure financed, they need shovels in the ground right away. And this is particularly true, as countries come out of COVID. We all know that infrastructure is one of the fastest ways to get an economy moving again, right? It has that high fiscal multiplier effect, meaning you put money into infrastructure, you get shovels in the ground right away; that turns into jobs, that turns into consumer spending faster and more effectively than just about any other kind of spending. So countries want that to happen quickly. The World Bank can do that very well. But it cannot do that very quickly. China can do that quickly. So we see countries saying yes to both just for different reasons.

SP: But is there also an element here of Chinese construction companies, largely state-owned enterprises, such as China Communication Construction, being able to take some of the value-added at least that the Chinese financing is creating, and extracting that because they are not having to operate under the same sort of restrictive practices that a Western engineering company would have to operate under, if they were to be financed or engaged in a project that was financed by a multilateral development bank. So there is this sort of asymmetry of requirements faced by Western engineering companies vis-a-vis Chinese ones, which means the Chinese package is very attractive to China, and that is why they are prepared to undertake it at a great speed, if you like.

RR: So national development banks in general, have an outbound financing strategy that involves boosting their own firms overseas. That is one of the main reasons they do what they do, right? We have export credit agencies like the US Export-Import bank, which exists specifically for that purpose. So yes, of course, that is a very important purpose of any bilateral development finance.

And here I am going to put on my Latin Americanist hat on for a moment and say, we have a recent book project called "Development Banks and Sustainability in the Andean Amazon", where we compare the Chinese DFI's to other DFI's, who finance infrastructure in the region, we really look at their environmental and social governance, and how it works out in the end. And what we found was before China showed up, Brazil's national development bank was the major lender to its neighbours for its neighbours to build infrastructure using Brazilian firms, so a very similar model to China. And well now every living and one now dead, Peruvian former president is either in jail or under investigation for a massive corruption scandal from that era. So national development, lending is really prone to corruption because it is meant to push the origin countries firms overseas, that is what it does.

And so, for countries that have really serious histories of corruption in this area, and here, again, I am thinking of Peru where I believe five or six former presidents are either in jail under investigation, and one having killed himself as authorities were closing in on him to arrest him because of the scandal, countries like that may want to look to co-finance projects between China and multilaterals, where there is an open bidding process, but they are really being able to harness China's interest in building up infrastructure and working together. So that is one of the reasons why it is useful to see where are the gaps from the World Bank? Where can Chinese financing fill in? And how can we best raise those standards so that it is not undercutting either on corruption or environment or social standards, the way national development finance, Chinese or otherwise, can do?

SO: Okay, Becky, just one last question, looking at the clock. You are sitting in America, obviously, but you have been giving a worldwide analysis of this. But if you were called in to see President Biden tomorrow, and he said to you, "Well, Becky, with your data, what would be your suggestion to us to basically push back on Chinese influence that they are gaining through this? How could we make a difference to American influence?" What would you say?

RR: Well, as Janet Yellen is in Africa right now, my Twitter feed is full of African analysts saying "Every time China visits, we get a railway. Every time America visits, we get a lecture." And unfortunately, we are seeing that pattern play out again. It is very clear from our data that developing countries don't want to choose between partners, but they have needs that are not being filled by existing development finance institutions. So that is where you need to be relevant. It is very clear why countries are going to China; they are going to China because they need infrastructure, they need connectivity, and they need investment.

So if you want the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) to be real, if you want it to be meaningful in your bilateral relations around the world, that is the space you need to be active in is coordinating policy investment and infrastructure in the way that the PGII hopefully promises to do. I hope that our work shows where there is a void that traditional Western development finance has not filled. A few episodes ago, you had on Eric Olander of the China Global South project, and I just want to underline something that he said. Countries are going to China for something they are not getting anywhere else. And if you want to be relevant, it is very clear that that is the gap, that there is more demand than supply right now, so step into that gap.

SO: Yes, I must say, some people disagree with Eric and because he has been slightly more problematic with America than others. But I am sure I speak for Stewart as well, we completely agree. We have said this many times on What China Wants. If we in the West want to push back on China's influence, then you have got to take into consideration what the world actually wants. And the world wants infrastructure, the world wants to be given connectivity, etc. And so it is very hard to see how that is a wrong message to be given. And if China is willing to do that, then that is something that's going to make China quite popular and spread its influence. It's as simple as that.

RR: Simple as that. Also, one more thing I'd like to add, if Joe Biden were listening, one more thing I would like to say is, we have just finished an era in which we had an unprecedented US Representative at the Head of the Inter-American Development Bank. That is the development bank that has always been led by a Latin American until the Donald Trump administration when he pushed through a US leader, and he pushed through a US leader with a very specific agenda of isolating China in a region that did not want to be asked to choose between China and the West.

I would say do the opposite of that, crowd-in Chinese money to multilaterals. Why? Because there is open bidding in multilaterals. What percentage of bids US firms win if they are not going through multilaterals, and they are just going through China - 0%. Of course, you do not win anything you cannot bid on. So why not have that money flow through multilaterals where you have a chance of bidding at it. And it has got to reach those environmental, social and transparency standards. Why not increase cooperation at those multilateral fora where you have a voice, your firms get to bid, there is harmonised agreed-upon standards. Chasing them out of multilateral fora is not going to reduce their influence; it is simply going to push it into bilateral directions, which is the opposite of what Western leaders say they want.

SO: Wise words. That is brilliant, Becky, very well said. Well, thank you so much for your time, that has been very illuminating indeed. And hopefully people, maybe not President Biden, but we know that a lot of policymakers listen to the podcast. And so hopefully, some of your wise words will be thought or ruminated on by those policymakers if we want to actually see a world where China's influence is not left unfettered through the development finance channel. So, thank you so much, and we will be back next week with some more What China Wants.

RR: Thank you so much, everyone. What a delightful conversation.

Share this post