Hello and welcome to the fourth episode of the What China Wants podcast.

Southeast Asia - an area of 680 million people, countless raw materials, and located in a strategically important corner of the world - has long been fought over by foreign powers. In this week’s episode, Sam and Stewart ask if it is still true today: is the region being contested by China and America, and if so, why? And what does this mean for the superpowers’ wider struggle?

You can also listen to the podcast on Apple, Amazon, or Spotify.

As always please do share, comment, and subscribe. We’ll be back next week to discuss the impending Great Split between China and the US.

Many thanks for listening.

***

Here is the transcript for the podcast:

Stewart Paterson: "The China ASEAN relationship has grown into the most successful and vibrant model for cooperation in the Asia Pacific, and an exemplary effort in building a community with a shared future for mankind."

Those are the words of Xi Jinping, and welcome to What China Wants. My name is Stewart Paterson, and I'm joined by Sam Olsen. Hello, Sam.

Sam Olsen: Hello Stewart.

SP: The subject today is Southeast Asia and the relationship with China and other great powers and the role that Southeast Asia might play in great power competition going forward. In terms of Southeast Asia, what people tend to mean by that is ASEAN - the Association of Southeast Asian Nations - with 10 Member States, there is, of course, also East Timor, which is not yet a member of ASEAN.

Sam, China and Southeast Asia, they have a long history, don't they of interaction engagement, whatever you wish to call it?

SO: Yes, China and Southeast Asia have been entwined for thousands of years now. And the first interplay, so to speak was definitely around trade. If anyone's been to Singapore, they might have seen the amazing Tang Dynasty boat that sank near there in about 830 AD, full of amazing porcelain and gold and silver objects, and intricate workmanship, which just shows the level of sophistication of trade at that time between Southeast Asia and China.

Politically, it's a bit more difficult. The first big sort of large scale interaction was an invasion by the Chinese under the Mongols in 1292 into Java, when the Javanese leader stopped paying tribute. There's been a sort of bumpy ride politically ever since in many ways. What's also interesting apart from the political side and the trading side is the cultural exchange. Confucianism, Buddhism have all come down over the millennia down into Southeast Asia from China. But there's been massive emigration from China too, starting off from the sort of 1400's and 1500's and particularly reaching a height, bizarrely enough, under European colonial rule when, as one historian put it, Chinese immigrants followed the imperial flags of Europe, and you saw huge amounts of Chinese leave, especially from the coastal provinces, into Southeast Asia, to the extent that now 10% of Southeast Asia's population is ethnically Chinese.

SP: And Sam, would you describe the relationship as being symmetrical? Or was it very much an asymmetric relationship between China and Southeast Asia?

SO: Well, good question. It was very much China looking at Southeast Asia as a source of trade, and for the individual Chinese person coming out of China, a place to live and to work. There was never really much input into China from Southeast Asia. But if you if you look at America, America is very similar as well that the relationship historically between Southeast Asia and America is quite asymmetric too, although the Americans, first of all, looked to Southeast Asia as a conduit into China.

Then, in 1899, when they conquered the Philippines from the Spanish, they became a colonial power, and that led them eventually into conflict with Japan. In the Cold War, Southeast Asia was considered to be a major area of dispute over communism or capitalism. America certainly went in hard with many countries like Vietnam and Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines as they tried to stop the domino effect. So yes, for both America and China, it's been very much asymmetric, but that doesn't mean that Southeast Asia hasn't been an important place for both powers to express their political and military power.

SP: Okay, so Sam, the asymmetry of the relationship with between China and Southeast Asia, this must be linked, is it, to China's view of itself as the Middle Kingdom and the history of the sort of tribute system? Can you explain that a bit?

SO: Yes, the tribute system, which people talk about, is where countries pay China tribute, whether it's in money or goods; often it was just in exchange for the ability to trade with China actually. And that has lasted for quite a long time.

There are people, especially Chinese scholars, who will dispute there was ever such a thing as the tributary system. But I think most people think that there was some kind of system in place, and the most famous countries were Korea, which was obviously fought over with the Japanese in the 20th century, but the Southeast Asian Nations definitely were on the front line of that too, if you take the tributary system as existing in the first place. But that raises an economic point for you Stewart. What is the current economic relationship between Southeast Asia and China; is it very equal because I know they're meant to be very important trading partners for each other. But what's the relationship like?

SP: Well, they are important trading partners for each other. The modern evolution of the economic relationship really goes back to the Asian financial crisis, I would argue and this is where the asymmetry began to open up. Because back in 1994, the combined GDP of what are now the 10 ASEAN member states was actually larger than China's - about equal size, but the ASEAN countries had a slight edge. You fast forward to today, and China's economy is actually five times larger than ASEAN's, and I think one of the reasons why that gap has opened up has been because, to put it bluntly, China has eaten ASEAN's lunch, in terms of global trade, particularly in manufacturing, so that the industrial policy that China pursued, post its devaluation of the RMB, in 1994, has meant that China has grown its manufacturing capability extremely rapidly, and at least part of that has been to the detriment of ASEAN.

In terms of current trade, what's quite surprising, actually, given the size of China's economy - it's about 16-17% of global GDP - and its proximity to Southeast Asia, is that actually only about 20% of Southeast Asian trade is with China. So it's big, it's very significant. It's in fact, as significant as intra-ASEAN trade, trade between Asian nations. But it's not quite as dominant as one might expect, given the size of China and its proximity.

There are though other dimensions to this, other than trade. There has been recently a very large increase in investment from China into Southeast Asia, and this reflects partly the migration of lower value-added industries from China, out into Southeast Asia, such as textiles, for example.

SO: What about America, the relationship with America? How does that compare economically?

SP: So it's a very different kind of relationship actually. The trade pattern between Southeast Asia and China is really typified by primary commodities leaving ASEAN and going to China. Whereas what ASEAN imports from China, are capital goods and components that go into ASEAN exports, largely speaking.

The relationship with America is really more of America being an end customer for ASEAN-produced goods, and a part of the value of those goods is actually originated in China. So a great example would be mobile phone exports from Vietnam, where Vietnam has grown its telecommunications industry very, very rapidly. But most of the components that go into those phones come from China, and the phones themselves end up all over the world, but Western Europe, and the United States are big end markets. So ASEAN tends to run a trade surplus with the West and a trade deficit with China.

SO: So does this mean that the inputs into ASEAN's, well Southeast Asia's economy, mainly come from China and if China cut off the raw materials or the manufactured goods into Southeast Asia, then Southeast Asia's economy would basically cease to function? Is that how it works?

SP: Up to a point. I think one point we have to make very clearly here is that, although we talk about Southeast Asia as one kind of geopolitical block, it's not a homogeneous grouping of countries at all. The economies are very different from one another, both in size and in structure. And of course, the political regimes are very different from each other.

And so it is true, for example, that if we look at say, Cambodian textile exports, a lot of the inputs into those exports come from China, and I've already mentioned Vietnam in terms of telecommunications equipment. Indonesia, on the other hand, is a trillion-dollar economy in its own right, and it's much more autarkic, by which I mean self-sufficient. And so it's hard to just generalise between Southeast Asian nations, certainly on the economics front, I mean, on the political front, I imagine Sam, you would have something to say about the diversity there.

SO: So yes, you're correct. The countries of Southeast Asia are definitely not united, politically or militarily and ASEAN, which is the regional group in the sort of EU equivalent, in theory, is actually very different to the EU because it has very limited centralised powers unlike the EU, and it is the region is still very much a collection of independent, independent states. So, politically though, the relationship with China is fascinating because some countries are much closer to China than others.

But that said, China is making a real push to be a friend to the region as a whole, to almost every country there. And if you look at the political outreach to Southeast Asia, then you see that proportionately, there's a lot more trips from senior politicians, for example, Wang Yi, the foreign minister, than there are to other parts of the world. And that's not surprising in many ways, because it is on their doorstep, but still, it does show how important the region is.

And a big part of that is economically, of course, but politically, and militarily, Southeast Asia is the gateway into China. And if you're sitting in Beijing, and you don't want to be encircled, then a big part of your worries will be about Southeast Asia being not entirely 100% friendly to China, which does give foreign powers, i.e. America, potentially the Europeans and the British as well, access to strategically important routes in towards China. And the desire to politically and militarily dominate Southeast Asia, for its own purposes, is a big reason behind the seizure of many parts of the South China Seas by China, which over the last 10 years or so, actually started under the nose of the Obama administration.

SP: Can you actually just elaborate on that, Sam, because what our listeners might not be aware of is that quite a large number of ASEAN member states actually have territorial disputes with China don't they? We're all used to hearing about the ambiguity over Taiwan's status. But actually, it's not just Taiwan that has a territorial dispute with China, is it?

SO: No, in fact, I think I’m right in saying that China has more territorial disputes than any other country in the world. And some of them are very long standing, some of them quite recent. But the South China Sea area, Southeast Asia is full of them, and countries like Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, they've all suffered from Chinese encroachment on what those countries believe is their sovereign territory.

But what you see is that China is carving out of control of the South China Sea, whether or not these countries put up any resistance, and ASEAN has been quite slow to come out against China, as an entity, and individual countries have tried and failed to get China to abide by a 2016 ruling, done by the United Nations, which said that their moves into the South China Sea were unlawful. But it's very difficult, Stewart, because you don't have the homogenous political units and China finds it very easy to divide and conquer.

SP: And so within Southeast Asia, because ASEAN is obviously a very consensus driven organisation, by definition, which of the countries seem to be doing Beijing's bidding the most?

SO: Well, I think, as you'd agree, there's a big overlap into the economic relationships. So, if you look at Cambodia and Laos, I think you'll be happy to say that they are the most economically intertwined countries with China, right?

SP: That's correct. Yep.

SO: Yes, and they also are the countries that are most politically intertwined with China too. But countries like Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, they all have good-ish relationships, and they have their ups and their downs with China. But politically, they try and find ways to work together in areas of commonality, but they're stronger than the countries like Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, etc, which are increasingly dependent, by accident and by design, on China politically, and as you will back me up, I'm sure, economically.

SP: So going forward, what we're painting a picture of here is a region, in the case of ASEAN, of 10 countries, 680 million people, a $3 trillion economy in aggregate, and this area of the world seems to be the front line in the geopolitical rivalry between the US and China, but actually, in many ways, it's broader than just the United States, isn't it? Because the UK has undertaken its sort of pivot to Asia, France is espousing a policy of greater engagement in the Asia Pacific, and obviously, the other Pacific powers such as Japan, Australia, etc, have a very strong interest in the development of Southeast Asia. So Southeast Asia seems to be becoming this sort of front line in the competition between ideologies and great powers. So what could the Western or the democratic sort of Alliance, if you like, do to help increase their influence in the region?

SO: Well, it first of all, it's important to note that during the Cold War, as I've already mentioned, Southeast Asia was on the front line communism and capitalism.

SP: That's why ASEAN came into existence didn't it, it was actually an anti-communist Alliance.

SO: Yes exactly, which is not so much the case anymore, if you look at communism being headed by China. But I think that today, you're seeing very much that every single country in Southeast Asia has got a pro-Western and pro-Chinese faction, and they're both struggling for power and influence within those countries, and they want to push their country towards one side or the other.

The Philippines is a great example where you've seen President Duterte, who's been in power since 2016, pushing his country more towards China. Now, it might be said that that's a rational decision, or some people will say that it's what's so-called elite capture. And his daughter who's the mayor of Davao, a big city in the south. She is following in her father's footsteps by actually creating four twinning arrangements, the four different cities between her city and in places in China. She is now the new vice president of the Philippines, and of course, it's likely that she's going to try and force a continuation of her father's policy towards China.

But I suppose the most important thing that the Western Alliance can do is to show the region more attention. For a long time, I think, people in the West have considered Southeast Asia to be a bit of a backwater. You haven't historically heard much about it in conversation, especially when it comes to businessmen and women sitting in Europe or America, looking east or west as the case may be. But that is beginning to change. And the UK, for example, has put a lot of store, because of its integrated review, into furthering ties with Southeast Asia. And now the UK has become an official dialogue partner with ASEAN, and it's got a trade commissioner in place, Natalie Black, who by all accounts is doing a fantastic job at raising the profile of British investment into the region. Other countries in the West are looking at Southeast Asia to France, Germany, etc.

But there is one country which is already doing so, and that's Japan. It has a rather complicated history with the region because of the war, but over the last few decades, has really been putting a lot of investment into Southeast Asia. And it fiercely competes against China for contracts all over the region, for example in Indonesia, or Vietnam or Thailand, Cambodia, there are a lot of new factories going in from Japanese companies, even though there is a lot of work also being done by the Chinese to extend their influence there.

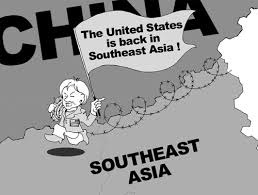

SO: So at the end of the day, parts of the West, especially including the UK, and Japan, are showing a lot more attention, a lot more love to the region, and that should pay dividends. But there is one country which doesn't seem to be doing that much more and that is America. Stewart, did you see the Biden summit, on the 16th of May a few weeks ago, when he brought together the Southeast Asian leaders?

SP: Yes. So this was obviously, Sam, an American attempt to push back against Chinese political influence in Southeast Asia, wasn't it? And you'll have stronger views than I on the on the political side. I haven't seen much commentary that's been very positive about it. Was it the disaster that it's been painted as or was it a constructive first step?

SO: I mean, economically as we've said before, China has replaced America as the leading trade partner in the region, and this has been very much reflected in some countries in the region in political terms. Biden was trying to recalibrate American political power in the region by bringing people together to celebrate 45 years of ASEAN-American ties, which, as you just pointed out was started in the midst of the Cold War.

But I think the reality is, is that it was a damp squib. And reading the local press in the various countries of Southeast Asia, there's really no one that's been very enthusiastic about what was said. I mean, other than the fact that it shows willing. But the actual measures, the very poor amount of money being promised, are far less than what China has been pumping into the region, and also far less than what Japan has been pumping into the region as well. Because don't forget, Japan looks at the region, as a strategically important part of its overseas engagement, too. But America under Biden just doesn't seem to be really grasping the nettle. And I don't know whether that's because they don't have the capacity or the willpower to be able to really step up to the plate, or whether they just have misread the room and think that they can give a little bit and everyone will fawn over them.

In reality, it was a nice thing to have done, but it really didn't hit the mark in terms of trying to reinforce the thought that America is back in the region after many, many years of decline. In fact Stewart, America hasn't even appointed an ASEAN ambassador, that post has been vacant for a long time now. And that, I think, just shows the importance that America places in Southeast Asia compared to other places in the world.

SP: So if America is not stepping up to the plate, as it were, to counter China in the region, aggressively, I suppose the other sort of factor that might keep a balance of influence in the region is if China's importance to the region actually slightly diminishes, particularly from the economic side. And here, I would point to a couple of factors.

I mean, clearly, in Southeast Asian economies generally, tourism is an important industry, right? And a lot of the growth in tourism in Southeast Asia in the last 10 years or so, has been driven by China's outbound travellers. And obviously, since COVID, that's completely disappeared. And with China continuing to pursue a zero COVID policy, there's no indication that those Chinese tourists will return anytime soon. And so that has obviously had a very debilitating impact on some economies, Thailand, in particular, but I would throw Cambodia in there as well as a country that was very dependent on Chinese tourists and Chinese visitors. And so that will diminish the importance of China somewhat.

The other issue, I think, is quite interesting here is that a lot of China's perceived economic influence, I think comes from the narrative that China creates around its economy, that in the future, it will be X, Y, or Z, and that your economic future as a third country is tied to China's future success. So it's all about jam tomorrow, rather than actually delivering today. And I think that's certainly been ASEAN's experience in terms of exports to China over and beyond just primary commodities.

So there must be a sense, I would think, that the current economic malaise that China finds itself in with a shrinking economy, as we discussed a couple of weeks ago, and really quite an ambiguous long term outlook for economic growth, that this change in dynamics, which is new, might well have quite a big impact on perceptions of China in ASEAN going forward over the next few years.

SO: You raise a very good point there about the perceptions of China, because the polling continues to show that across the region, with a few exceptions, but for the majority of countries in Southeast Asia, the populations there would prefer to be more allied to America than they would be to China. It is the elites that are driving the closeness; as I mentioned, there are elites within each country which are choosing the pro-China path. If the economic carrot is not there for closer integration then you're right Stewart, I think that China does not necessarily have set in stone a rosy future in Southeast Asia if the economic relations degrade.

SP: So that's an interesting point. Perhaps one of the issues this raises is that China's trade necessities are changing as their economy changes. So as China's alternative energy, for example, generation picks up, as it becomes more energy efficient, maybe the Straits of Malacca, or, the transfer of hydrocarbons through the Straits of Malacca become less important. Obviously, China has tried to circumvent the Straits of Malacca, through pipelines across Myanmar, for example, in the pipelines into Central Asia and from Russia.

And obviously, commodities such as lithium and cobalt, out of Africa, have become more important to China. So it could be that China's trade patterns are evolving in a way that puts a greater emphasis or a greater importance on other areas of the world. And it's noticeable that BRI, the Belt and Road Initiative, which is China's Great overseas, push in development infrastructure, seems to be being concentrated in Central Asia and in Africa, up to a reasonable point. And perhaps what this suggests is that we should do a podcast on the way Belt and Road is spreading out across across the world into other areas beyond Southeast Asia.

SO: Yes, I completely agree. The developing world is certainly in the political and military sights of China, and it's worth exploring that more. But, just wrapping up Southeast Asia, it's obvious that China puts a huge amount of emphasis onto developing relationships - political military, and by the sounds of economic relationships - there. The question is, I suppose what we're asking is, how long is that going to be successful if their economy starts to splutter? But also the other thing is true, which is that, does America have the interest or the capacity to really push away Chinese influence? And I suppose time will tell on that.

But in the meantime, thanks very much for listening. And we'll be back next week with one of the many podcasts that we've been suggesting over the last few weeks Stewart.

SP: Thanks very much to our listeners, and thanks, Sam, good to chat.

Episode 4: Is Southeast Asia the Frontier of Great Power Competition?