Hello and welcome back to What China Wants.

Earlier this week we announced the launch of our new think tank, the Evenstar Institute. Dedicated to measuring and understanding evolving national influence, our current programmes are the China Influence Index and Macro Supply Chain Risk.

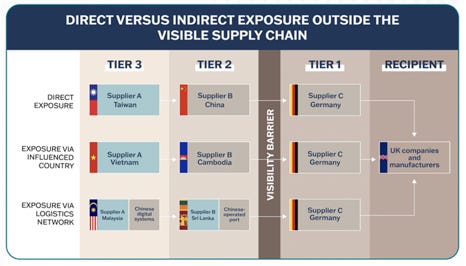

In today’s episode Stewart and Sam speak to the Evenstar Institute’s Director of Research, former LSE academic Dr William Matthews, about the paper that Evenstar just published. “An Overlooked Risk: China’s Indirect Influence Over the United Kingdom’s National Security Supply Chain” shows how the UK’s national security supply chain is heavily exposed to China in three separate ways: directly, indirectly (through third party countries that may be heavily influenced by Beijing), and through China’s strong position in the global logistics network.

Here is the Executive Summary of the report, which we discuss below:

The United Kingdom’s national security supply chain is exposed to China in three ways: directly, indirectly (through third countries), and through China’s strong position in the global logistics chain.

Beijing has repeatedly used its influence in trade and its control over certain raw materials to achieve its own strategic and political aims, for example through cutting off supply to countries which it disagrees with.

There is every reason to suspect that Beijing would employ similar tactics to achieve its strategic aims if relations with the UK were to significantly deteriorate.

Although effort has gone into de-risking the UK’s direct exposure to China, more work is needed to reduce the indirect and logistics risks.

Using Southeast Asia – a key source of goods and materials for the UK – as a regional case study, we show how the UK’s national security could be readily compromised by China in the event of a downturn in relations.

You can also listen to the podcast on Apple, Amazon, or Spotify.

As always please do share, comment, and subscribe. We’ll be back soon with more What China Wants.

Many thanks for listening. In the meantime, if you would like more information about the Evenstar Institute and our research, then please email me sam.olsen@evenstarglobal.com

***

Here is the transcript:

Sam Olsen: Hello, and welcome back to What China Wants with me, Sam Olsen, and as always, Stewart Paterson. Today we have got some very exciting news. For a number of years now, we have been running What China Wants as a newsletter, and in podcast form. We are now launching today a mothership What China Wants, which is called the Evenstar Institute, a non-partisan, not-for-profit think tank focused on measuring and understanding the evolving nature of national influence in the 21st century.

What does that mean? Well, the first thing we are looking at, and the relevance to What China Wants is we are looking at Chinese influence across the world. To do so we have developed a very detailed methodology, using quantitative and qualitative data; using tens of thousands of quantitative data points and looking at interviews with people from around the world to help us to put the qualitative side in as well. Stewart and I have been working hard on this for a while now, along with the rest of the team from Evenstar. Today, we are going to be talking about the first piece of research that The Evenstar Institute is launching. To do so, Stewart is going to be interviewing myself and our colleague, William Matthews, who is our Director of Research, about exactly what is in this new paper. So, Stewart, back to you,

Stewart Paterson: Thank you, Sam, and welcome, William. William is a fluent Mandarin speaker and a specialist in Chinese Comparative Social Science and International Relations. He has 10 years’ experience researching and teaching on China, drawing on a range of disciplines including political science, history and anthropology. Before joining the Evenstar Institute, William was an academic at the London School of Economics, and he received his PhD from University College London.

So William, well, congratulations on this new piece of research. It is entitled 'An overlooked risk: China's indirect influence on the UK's national security supply chain'. So, William, for those who perhaps do not follow issues of national security closely, perhaps we could just kick off by asking you how exactly do you define the national security supply chain? And in layman's terms, what does that actually mean to people?

William Matthews: We have taken a broad approach to national security, and we have gone into this through the lens that national security is not just about bombs and bullets, it is about much more than just purely defensive capacity in the defence supply chains. Our approach is to understand national security, fundamentally in terms of a country's ability to act autonomously, without having to align itself with the influence of other actors.

We look at this not only in terms of defensive capacity, but also aspects like human security. So, the ability of a country to provide for its people in terms of food, health, environment, and so on, of economic prosperity, and of government function. In our view, compromising a country's autonomy over any of these areas would constitute a threat to national security. So that is the lens with which we have then gone on to look at what we are calling the 'national security supply chain' in this research. So we do not just mean the defence supply chain here, we are looking at anywhere in the global supply chain feeding into UK national security, that could represent a vulnerability to any of those core areas.

SP: That is fascinating, William, and in the report, you talk a little bit about the various domains or 'sectors' as you call them, in which China can create influence, and you also have the 'enablers' of influence. Could you just briefly explain what you mean by that, and talk us through the sort of process by which the influence is built?

WM: Sure. So, we have looked at this using a model which is designed to trace the kind of causal chain of influence building. We do this across different sectors, all of which constitute, if you like 'a domain of' a country's key activities. These are things like defence and security, politics and governance, economics and finance and so on. And essentially, we look at influence, so for example, the influence of China in another country would be the degree to which China is able to dominate one of those sectors in a way that constitutes some kind of constraint on the autonomy of that country to act.

When we are looking at 'enablers' of influence, this is the specific means by which that influence is built up. So that could be, for example, through things like diplomatic means, it could be through ownership of key companies or stakes in key companies. In the case of China, it could also be through things like the activity of the United Front Work Group, as a means of building up influence on the ground. Then we look at these, again, through that ultimate lens of national security as a potential target.

SP: Brilliant William. Well, I am sure we could probably do a podcast on each and every one of the enablers, and each and every one of the domains, but not now. So, I would just like to move on, and ask you Sam, why do you say China is a risk to our national security supply chain?

SO: Well, Stewart if you go back to the early days of What China Wants, we have always been very centrist in our approach. We are all Sinophiles, but we also recognise that China i.e. the Communist Party does want to change the world order, and that might not be to the benefit of the UK and its Western allies. This is always the lens through which we look at things, and I think that with regard to the UK's national supply chain, there are vulnerabilities. For a start, 30% or so of the world's manufacturing is in China, and not just directly impactful for the UK, but so many of the components, raw materials, etc, that we get from third countries comes originally from China.

One of the examples we give is looking at British military uniforms, where many of them were made in Cambodia, and we show that two thirds of the inputs into Cambodia's garment industry come from China itself. So China could literally turn off Cambodia's exports of garments in one day, and that would be a problem for us if we were waiting for uniforms.

SP: Presumably, that is not the most serious of the threats is it?

SO: No, it is not. But it is an indication of how one can imagine threats materialising from China putting pressure not only directly on withholding things from the UK, but also indirectly from the UK, as well. And the thing is, is that China does have a lot of form in using trade and its control of aspects of the supply chain as a weapon to achieve its strategic goals. There are so many examples, whether it is imports of salmon being cut off from Norway, because they were angry about the award of the Nobel Prize to Liu Xiaobo, or whether it was banning bananas from the Philippines over an argument about the South China Sea, or rare earth materials being exported to Japan in 2010, because they did not like what Japan had done about a fishing incident. There are many, many examples of where China has used that, and I think that it is incumbent upon us to prepare for a situation where China does want to achieve strategic goals with the UK, where it uses that demand to force Britain to acquiesce on things by withholding, either directly or forcing other people to indirectly withhold things from the UK national supply chain.

A really good potential example is something we talk about in the paper, which is that there are 800,000 people in the UK who have jobs related to the motor industry. If China decided to cut off parts, many of which are made in China, let alone all the semiconductors that are made in Taiwan that could be cut off by Chinese action against Taiwan, then the impact on the UK would be very severe indeed, not only economically because of slow production, but also socially, because so many of those people would potentially lose their jobs or at least see a downturn in their working week, which would have an impact on their families. So, as William says, the lens of national security has to be looked at much broader than just bombs and bullets. To that degree, we have created this paper where we look at the potential risk, directly and indirectly from China.

SP: Yes, so it is interesting, you mentioned rare earths because, of course, we have just had the Section 232 report in the United States into their dependency on permanent magnets, which is a crucial part of the defence supply chain, and I am quite sure that we are at least as dependent, if not more so, than the United States on China for those. But I suppose, William, a lot of the report is about the indirect risks from China. Perhaps some of the more direct risks and routes of influence such as Confucius Institutes, for example, and the threat that Huawei posed potentially, and Hikvision with their surveillance equipment, these are sort of relatively direct risks in the realms of technology and media, but can you elaborate a bit more on the indirect risks, perhaps stemming from the enormous influence that China has created in third countries?

WM: Sure, so one of the key points of this research is precisely that, that indirect risk or indirect exposure to China is as significant an issue as those kinds of direct exposure that you mentioned. Now, indirect risk can take a few different forms. It could be the knock-on effects into a country further along the supply chain, so something like the example Sam mentioned about uniform manufacturers in Cambodia relying on Chinese inputs. But it can also be the result of China executing influence over intermediary countries, or suppliers where it has established influence. Again, we have precedent for China doing this. For example, in 2021, after Lithuania opened a Taiwan Representative Office, China attempted to use direct targeting against Lithuania, which had little effect. But what China then did was target firms which themselves source products from Lithuania, an example being Continental, a German automotive manufacturer. Their products were prevented from clearing customs in China, and this kind of action ultimately led to increased political pressure on Lithuania from Germany. What we have got there as an example of China using its influence over a third country to pressure another country.

Now, what we have found looking at our regional case study of Southeast Asia is that in this region - this is a region crucial to the UK supply chains - it is also a region where China has a very high degree of influence. We find that there is a particular risk in terms of countries from which the UK imports high volumes of goods and components and so on, Vietnam and Thailand are good examples. Now, these have relatively a moderate degree of Chinese influence compared to a country like Cambodia, but nonetheless, that moderate influence combined with that volume of imports to the UK, constitutes a high level of indirect exposure to Chinese influence. This is a level of influence which has increased significantly over the last 10 years. We should, I think, expect, as China has shown willingness to use indirect methods to impact supply chains, we should be prepared in the event of any kind of downturn in relations with China or something like this, to see similar targeting of UK supply chains going through regions with high levels of Chinese influence like Southeast Asia.

SP: So, Sam, a lot of our listeners will have heard of and be familiar with the Belt and Road Initiative. We have recently had this situation where there has been a healthy, rigorous debate in Germany about the Chinese acquisition of a stake in the port of Hamburg. Some years ago now, the Chinese took over the port of Piraeus, which is obviously a fairly iconic Greek economic asset, as it were. China is the biggest trading nation in the world, it spends a lot of money on logistics, on shipping, it has huge capacity in shipbuilding. How important do you think the global footprint of China's logistics companies is as a vehicle, a channel of influence? And would you worry that this enables them to disrupt global supply chains in a in a significant fashion?

SO: First of all, it is important to note that there is very strong historical precedent for a country dominating trade, dominating logistics to have a cutting and winning edge in war, the UK being a prime example of that. In the First and Second World Wars the UK dominated the world’s maritime fleets, and its ability to shift products, food, etc. munitions around the world was such that the Germans and the Japanese simply could not match it. For normal peacetime, there is absolutely no problem with China being able to have a dominance over global trade and to be able to have that strong position in the logistics industry. But, if and when we get to conflict with China in whatever guise, whether it is kinetic or merely economic sanctions, then we can expect China to do what we did and what other countries in the past have done with their logistics control, and to use that to their advantage.

There are a few things you mentioned there about China and the ports. Well, they now own 93 ports in 40-50 countries and have one of the world's largest shipping container companies COSCO, but perhaps more importantly, they are increasingly using their control of ports and their exposure to the global logistics industry to put their own digital infrastructure in. The most prominent of that is a system called LOGINK, which is actually a really good idea in many ways, because it brings together lots and lots of different aspects of logistics software into one closed system, which makes things far more effective, far more efficient, and you can ship something from A to Z through different ports, different lines, and make it much easier to track where it is going.

The problem is that, for the West, that system LOGINK is owned and run by the Chinese, which means that the Chinese not only have access to understand where all supplies for the West are going - whether that is uniforms or whether it is bombs, bullets, or whether it is much more prosaic things like for example, batteries, which are also needed for the UK's and Western supply chains - it can see where they are going, but also, if it is feeling mischievous, can actually divert those shipments, and it gives China huge amount of control over what can and is shipped around the world. So I think that is an important aspect to look at with regard to the Chinese control over the UK national supply chain and one that really has not been spoken about much.

SP: Okay, so William, clearly yes, logistics are a threat, and our supply chains are intertwined with China. So what is the solution? Onshoring and friend-shoring, are the sort of buzzwords of the moment in terms of building supply chain resilience. Perhaps it is ironic to be talking about friend-shoring when at the moment, I think the UK are waiting for a delivery of a particular type of press that we require at Aldermaston from Belgium and the export has been blocked by the Green Party in Belgium, although presumably that is a surmountable problem. Are onshoring and friend-shoring the answer, because clearly autarky would be very expensive, and a lot of these components that we depend upon in the UK, we simply do not have the scale of demand to do everything ourselves?

WM: So onshoring and friend-shoring are solutions, but they are solutions with significant challenges, simply because of the degree of exposure of supply chains to China directly and indirectly. A good example of this would be Apple, a major company that produces 90% of its products in China, it has estimated it would need at least eight years to move just 10% of that capacity out of China. And it's not only under direct exposure through that manufacturing, but also, if we look at its suppliers 150 out of 180 of its suppliers continue to have operations in China. So there is also that huge degree of indirect exposure. So, in thinking about onshoring, and friend-shoring, the UK Government and companies need to be thinking about indirect exposure as a major concern. Where do alternative suppliers source their raw materials? Where are these located? What is China's influence like in those alternative locations?

As part of this report, at Evenstar we researched this in relation to technology and manufacturing companies, and we drew two main conclusions from this. The first one is that a key challenge is that there are relatively few alternatives to Chinese suppliers in Western or Western-friendly countries for a lot of advanced components. The second challenge is that when those alternatives do exist, their production capacity is far lower than that of Chinese competitors, typically. So, this presents significant issues as companies are attempting to shift their supply chains. For instance, one company we looked at had seen a huge upsurge in demand as a result of these processes. While it is able to procure 97% of its components, there is 3% that are in short supply because of supply chain issues. But those 3% are actually essential, so it creates a bottleneck on production output. So, a lot of this is also about what are the particular chains and links in those supply chains? How can these be mapped, and that step of getting that thorough knowledge of direct and indirect exposure at all stages is crucial to making onshoring and friend-shoring a successful solution.

SP: So Sam, maybe I can just come back to you finally, with I suppose two questions. What are your ultimate conclusions from this report? And secondly, where can our listeners expect this research to go in the future, and what capabilities does the Evenstar Institute have that might be of use to them?

SO: Okay, so the most important conclusion is that, like it or not, Rishi Sunak, the British Prime Minister, announced in that speech he gave recently that the 'Golden Era' with China is over, and actually we need to be more pragmatic and understanding and dealing with a strategic competitor like China. That means that we have to be more cognizant of the risks that China poses to our supply chain. And that is not just about a narrow focus on the specifics around warfighting ability, but on much broader national security definition that we have described. That is not just about stopping exposure, but as William pointed out, it is about building up the capacity for the UK to bring the production abilities back onshore, not only to our shores, but also to friend-shores, and to make sure that we have a much more robust supply chain. So I suppose the purpose of this paper is to really kickstart the discussion at government and private sector levels to say, what can we all do together to make the UK national security supply chain more resilient and more fit for purpose, considering the changing relationship with China?

I think in terms of more research, well, our plans are very simple to focus on the China Influence Index, that's one programme and Macro Supply Chain Risk is the second programme. Obviously, this paper brings those two things together, but the next paper will be around China's influence in Southeast Asia, which we hopefully will be launching around Chinese New Year’s time. That obviously brings together some of the issues we just mentioned about supply chains, considering how important that is dangerous to the UK, for a variety of different reasons. We are very excited to see what we can do with the Evenstar Institute. We are looking at influence in the 21st century, and it's not just about China. To be clear, we are looking at other countries as well, and more of that to be released soon.

SP: Sam and William, thank you very much indeed, and we look forward to hearing from you again on What China Wants in due course. Thank you.

SO: Thanks. Goodbye.

WM; Thank you.

Share this post