Hello and welcome to Episode 22 of What China Wants.

We are in the middle of the National Party Congress as we record this, and Xi’s speech aside (which we covered here) there is little to report as of yet. So we thought we would take the opportunity to talk to Stefan Aust, the co-author of a magnificent new book called Xi Jinping: The Most Powerful Man in the World.

(Stefan Aust was for many years the editor-in-chief of the political weekly Der Spiegel, Germany's most influential news magazine. He also wrote the book The Baader-Meinhof Complex, which was turned into the 2008 film of the same name.)

Some highlights from our discussion:

The authors had pushback on the book by certain quarters in China, who felt that Xi Jinping was too revered to be discussed like this.

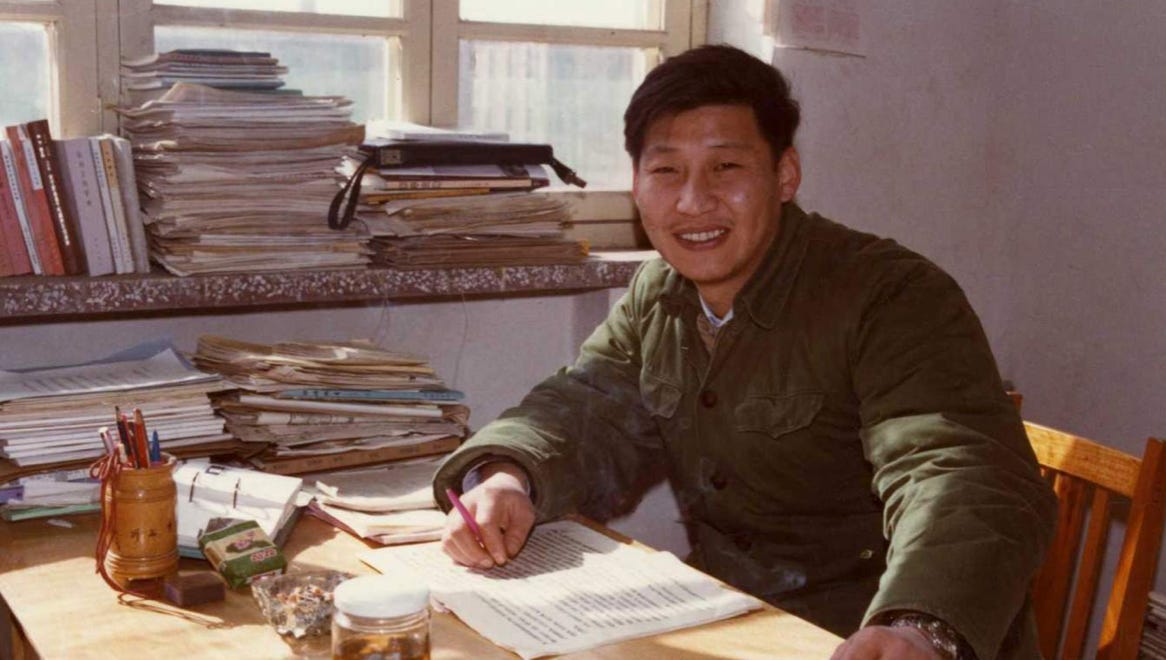

The authors believe, as many commentators do, that Xi is a product of his hard upbringing during the Cultural Revolution.

"Under Xi, China has turned inward, and Stalinism is back with a vengeance, grievance-fuelled nationalism”.

The general belief that Xi wants to be the new Chairman Mao is perhaps a reflection on the thoughts of others rather than what he wants; instead, Aust believes he behaves more like a monarch of old.

Xi’s centralisation of power and his recent related policies are likely to be a mistake.

You can also listen to the podcast on Apple, Amazon, or Spotify.

As always please do share, comment, and subscribe. We’ll be back next week with more What China Wants, reporting on the actual Congress itself.

Many thanks for listening.

***

Here is the transcript:

Sam Olsen: "At the institutes in Leipzig and Freiburg, we encountered no problems at all. But a few days before an online event hosted by the institutes in Hanover and Duisburg-Essen, the managing directors rang us. The head of the Chinese mission in Dusseldorf had intervened personally to prevent the event from taking place. The issue was not the content of our book, we were told, rather, according to the objections from the Chinese side, "you can no longer talk about Xi Jinping, the way you talk about any ordinary person, he is meant to be untouchable, and non-negotiable from now on"."

The question is Stewart, is Xi Jinping really that powerful, that revered, that we can't talk about him anymore? Well, that's what we're going to find out today, by interviewing the co author of the book that that extract came from, Xi Jinping: The Most Powerful Man in the World, Stefan Aust, welcome. Now Stefan, you're a German journalist, and you are the former editor-in-chief of Germany's leading news magazine, Der Spiegel and the author of numerous best-selling books, so I see on your bumph, including one about the Baader Meinhof complex, I believe?

Stefan Aust: Yes, that was actually the biggest success I ever had, but that was a long, long time ago.

SO: Okay, well, I think this is going to be more of a success, because we have heard that the feedback for your book for about Xi Jinping is pretty good. I suppose the first thing I want to ask you is, were the Confucius Institutes really trying to get in the way of you talking about Xi Jinping, as per the extract from your book. What was happening there?

SA: Actually, the interesting thing was, Adrian and I, we did another book about 10 years ago. For context, I had been in Singapore, and talked to a German professor of economics, and he told me how the influence of Confucius is growing in the Chinese world. And when I came back, I talked to Adrian, and we were discussing about that, and we decided to write a book, 'Coming to World Power with Confucius'. And that was interesting for us, especially for him, because he had lived in China for about 10 years, and looking back into the Mao Zedong period Confucius was a no-go. Right now it looks like Xi Jinping is putting together Chinese tradition, Chinese history, Confucianism and the communist ideas, and he is concentrating more on China as a country itself and as a matter of fact, he is trying to keep in power as long as he lives.

And the interesting thing for us was that because we wrote this Confucius book, we were in contact with the Confucius Institutes - at that time (2012), they were starting or at least growing into universities all over the world. So we worked together with them, even with this new book. And what we did not know was that they took parts of the book that they wanted us to read in this online discussion, and sent it to China for approval. Then they get an answer, and they said, "No, there will be no discussion, or whatsoever presentation of the book, with the Confucius Institutes." And you can imagine we had invited a lot of people and a lot of people had registered. Actually, it was not so many because of the pandemic, so we’d made it digital, we made it public.

Then you can imagine the university in Hanover and the University of Duisburg decided 'now we are going to do it ourselves', so then we had I think 450 people in Duisburg and later on, we had a big event at the University in Hannover and there were 600 people. So you can see that decisions of authoritarian or dictator's countries are not always very smart. They really helped us a lot.

Stewart Paterson: So Stefan, that was some welcome publicity, perhaps. But let's start with Xi Jinping and a bit about his background. What is there in his background, do you think, that has shaped the person that he is today?

SA: Well, his father was among the group of less than 10 people who were really important during the revolution and around Mao Zedong. But in fact he was not straight on Party line, he was a little bit more liberal than others. Actually his wife, and the mother of Xi Jinping, was as well. So he really got into trouble, and was imprisoned. Xi Jinping grew up in a very small village under the earth - not really a cavern - but it was a rather hard life.

And then during the Cultural Revolution, he was not on-line as well, and he was put in prison and was isolated. But nevertheless, I think it was because of his family background, and the story of his father being so important on the side of Mao Zedong, that he didn't try to emigrate or try to go somewhere else. This made him believe more into the Party history and the Party ideology, plus that, I think, into the tradition of China, he brought the Communist Party back into the Chinese tradition, and the culmination was Confucius.

SP: So Stefan, a lot has been said about Xi Jinping Thought, and obviously, some of his philosophy has been written into the Constitution almost. But is he a deeply ideological man? What does he actually really deeply believe in, other than the fact that he should be in power? Should we think of him as a communist purist?

SA: No, I wouldn't think so, but he is more on the Communist line than the politicians that have been after Mao's time before. I think the most important thing for the economic rise of China is opening the country and becoming part of the world economy, and for a certain time, be, what we always say, 'the workbench' of the world. The strongest part that China has, is the amount of people, their intelligence and their willingness to work very hard. So in a certain way, after Nixon went in the 1970s, and talked to Deng Xiaoping, and they opened the country, they changed the economy.

When I look back into German history, or the history of the Soviet Union, you could go to Berlin, and look across the wall. And on the east side of the wall, you could see a country with people that were exactly as intelligent as the people in West Germany, but the economy did not work, because it was a communist economy. There was no private enterprise whatsoever, and this just didn't work. So we were always convinced that communism wouldn't work. But when you look to China, you can see that a communist country is able to be very successful in an economic way, if the economy is, in general, a market economy, or if it's a capitalist economy.

And then that is the two power parts of the China after Mao Zedong, you have a market economy, the capitalist economy, with a lot of contacts to other countries, they are part of the world economy. And at the same time, you have the one-party system. You can imagine that this one-party system always has problems with the private enterprise sector, because the power is with the Party and the bureaucracy, but the money is with the others. And I think our ideas that we always had was that if you have a market economy that will develop into a democracy. What was seen from our side, as let's say, a hope, for Xi Jinping and his Party, it's a danger. This is why he has been fighting corruption for years, but the question - who is corrupt and who is not? - this is what he decides. So he is staying in power with all these campaigns against corruption, but which is in fact, the way to keep the power in the hands of the Communist Party and in his own hands.

SO: So it's interesting you say that, because one of the things that you explained in your book is - if I just read the quote - "Under Xi, China has turned inward, and Stalinism is back with a vengeance, grievance-fuelled nationalism." You spoke about the corruption campaign, which has obviously been quite prominent since he started. But what you're saying there is that actually, China's changed its ethos, really, way beyond the corruption campaign and the operational side of things. What's your evidence for Stalinism being back with a vengeance and grievance-fuelled nationalism being at the fore?

SA: Well you can see in almost everything he does and everything he says that he is coming back to the ideology of before Deng Xiaoping, more back into the ideology and the ideas that one person has to stay on the top of the power, and that the Party has to control everything. You can see now during the corona pandemic, that he even uses the idea of his zero COVID politics, to keep control over the people, which in the end, is not very successful, if you look at the economic development of the country. It's not good for the economy, and in the end, I don't believe that it really functions, but that's another question.

But you can see that the main reason for the success of the Chinese economy was opening the borders and to have contacts to all the other countries in the world, to build for them, to sell computers full of things to Hamburg, to New York and everywhere, and at the same time to import things. So that means having an open society at the same time, because nobody was living like in East Germany; if you wanted to leave the country, they could leave the country, they didn't build a wall. But you can see that Xi is concentrating more on the Chinese economy, and the Chinese tradition, and the Chinese history, and the Chinese borders. It's very hard now to get a visa to China, the good reason is always Corona, but in fact, he is trying to close the country, at least in part, again.

I'm not quite sure if he will be very successful with that, because when you can see that business partners they have from Germany or from America or whatsoever, when they have to go into quarantine, before they can start working or don't get a visa at all, they think 'maybe we can invest in Vietnam as well, and we can invest in Indonesia, or in or in India'. I had a discussion with the head of the Economic Chamber, the German one in Beijing just today, and he said that the economic actions of German companies go or start to go to other countries excepting China because they don't like to be regulated from dusk to dawn.

SP: So Stefan, those are interesting points you make there, because one of the observations that has been made in a lot of democratic countries looking at China and its economic relationships with the rest of world, has been that German industry has had a very symbiotic, or apparently symbiotic, relationship with China compared to other countries, that companies like BASF, and the big auto companies have dominated European FDI into China. And that actually, the trade relationship between Germany and China has been relatively symmetric, relative to most other countries, which have had very asymmetric relationships with China. And that this has led to a kind of fairly soft stance from German policymakers towards China.

Do you think that Germany's attitude broadly outside of the business community towards China has changed very dramatically in the last few years? And if so, to what would you ascribe that change?

SA: Actually, I don't think that, that this has been changing over multiple years, because most of the people don't realise that it's hard to get a visa. The discussions about this became bigger after the Ukraine war, after the attack of Russia against Ukraine, and that obviously, China is on Putin's side, or Xi Jinping is on Putin's side. And now we've had an experience that we didn't have before that. We imported almost 50% of our natural gas from Russia. When the war started, there were discussions here, we cannot take the Russian gas anymore, and then they more or less shut it down. So in fact, we were in an economic way, very dependent on Russian gas. This is a real problem.

I don't think that the dependence on exporting cars or whatsoever to China, or importing from China, makes us so dependent on China. If we couldn't sell our cars anymore to China, Volkswagen and Mercedes would have big problems, and the German industry as well. But I don't think that it is as dangerous as being dependent on energy from another country. I can repeat all these numbers, that economic experts said in this conference today, but I was quite surprised that we are not so dependent if you compare it to energy. We are not investing so much in China, they are more investing here. And we are investing I think eight times more than in Switzerland than in China. Actually, I am not quite sure whether we are more dependent on China than the United States. I mean, imagine who builds all these computers and all these technical things that they sell under American labels, it comes mainly from China.

I think it's not bad, if I may add that. I don't think it would be good for us, and I don't think it would be good for the world, if we would have a division into two parts, again, like during the time of the Cold War, that you have a socialist bloc on one side, and the capitalist bloc on the other side, and they don't talk to each other, they just see that their nuclear bombs are strong enough to be able to attack the other. I think the fall of the wall, and the opening of the countries was not bad for the world. And if you see that a population of 1.4 billion in China is not that poor anymore, this is quite good. We couldn't send enough humanitarian help to China to other countries otherwise, so I think it's good that these countries develop themselves, and make business and I think it's good to make business with them.

But they are businessmen, and I think it's important that we will be or stay to be businessmen as well, and say to them, that the conditions from one side to the other side must be the same as the other way around. Think of the situation like that of a junction in Beijing. If you stand in the street, and you see how people cross the street, they are fighting for the way to cross the street - you probably saw that a couple of times - I was always quite amazed by that. But you can see they look at their own interest, and I think the best way to fight that is to look after your own interests as well, and then try to find a solution. The solution will not be to say that we are educating them and telling them in which way they have to organise their country, they wouldn't do it anyway. So I think it's good to say ‘this is our interest, and if you don't agree to these conditions, then we talk to other countries and other parts of the world’. But I think globalisation is not bad, and I don't think it will be over.

SO: So Stefan, it might be ironic to some that we're talking about a communist 'Great Man', given the left's view of 'Great Man' history. But to what degree do you think that the China of 2022 and beyond has been shaped by Xi Jinping himself? Or was it always going to look like this anyway?

SA: I think the influence of single persons can be very strong, but they make only a career when the situation is in a way that they can make a career. If he would have positions that are completely different from the interests of big parts of the population, and big parts of the political world there, he would not be able to make a career. You can see at this party event, there are 2,200-and something people who act like in a big show, and obey whatever they have to say. This is not the world I would like to live in, I'm a child of the Western world, and I'm in favour of democracy and the liberal world and travelling everywhere.

When I see it, I know this is not the world I would like to live in. But on the other hand, we cannot tell them all how they can behave. The German Kaiser had this wonderful phrase, that translated as 'the German ideas should save the world', which is complete nonsense. We have to see that other countries develop in their own way. We can say what we think about it, but I think nevertheless it is good to have connections, and if there are conflicts, we should try not to bring them into situations where they then start a war.

SP: So Stefan, obviously not everyone in China believes in Xi Jinping's programme of national rejuvenation, and certainly not everyone within the Party approves of his style of leadership, or even the content of his leadership. So if we look at the next five years, assuming that the Congress results are as we expect, with his consolidation of power being complete, what does he have to do over the next five years, do you think, in order to ensure that he is still around in five years' time? What are the challenges that he must rise to, in order to ensure survival?

SA: I think that he’s made a big mistake. I think one of the most important things in a democratic state, but even in a non-democratic state, is that you have a certain way to change the people and the group who is in power. I think one of the best things in the American Constitution is that after World War Two, it was written in the Constitution, which was not in the Constitution before, that the President can only be president for two terms. I think that is very good.

Actually, the Russians copied that after the fall of the Soviet Union, and after Russia became a state itself, that it was put in the constitution that the President is only allowed to be in power for two terms. And the first one who changed that was Putin, first in the way that he made Medvedev the President and he became the Prime Minister, and then he changed it again. I think the best thing in a democracy is not to vote, but to be able to vote somebody out of power. This you see in democracies, when politicians are too long in power, the rest of the time, they use to stay in power, because it's not only one person who is on the top, but it's always a group of other people.

So I think it was a very good idea when Deng Xiaoping, after Mao, wrote into the I think the constitution of the Party and of the state as well, that somebody has to is only allowed to stay on top for two periods. And I think that was a very good decision. Because Xi Jinping is changing that, he's trying to secure his power. But that in the end, is not very good for the country, and I'm not sure whether it is good for him, himself at the same time. I think that's a big mistake. Most of the time, when the king or a dictator, or even a democrat is too long in power, the rest of the time after eight or 10 years, there is nothing else for him to do than to try to stay in power, and sometimes to start a war to stay in power.

SO: Many people are saying that Xi wants to be the new Mao, and I know you talk about this in your book, but what do you think is the reality, that he does actually want to be considered on a par with Mao? Or is that just people projecting their thoughts onto him?

SA: I think that is what people project now because Mao is the big person in the Communist party, and of the Communist revolution, but I think Xi Jinping, if you really read what he says and what he has written once more, he wants to be in the tradition of the monarchy. He is not only, let's say a convinced communist, but he thinks in bigger perspectives.

SP: Well, Stefan, thank you so much for joining us, and to our listeners who wish to buy the book, the English translation is available, it came out a couple of weeks ago, Xi Jinping: The Most Powerful Man in the World,.

SO: Thank you Stefan, and good luck.

SA: Thank you. It was interesting to talk to you, thank you very much.

Episode 22: Xi Jinping, The Most Powerful Man in the World