Hello and welcome to Episode 20 of the What China Wants podcast.

The FT and others reported a few days ago that American banks would exit China if Beijing launched an attack on Taiwan. “Heads of BofA, Citi and JPMorgan say they will follow Washington’s orders in the event of conflict” warned the pink’un. The paper went on to quote JP Morgan’s Jamie Dimon as patriotically claiming that “We would absolutely salute and follow whatever the American government said” when it came to divesting from the PRC.

What’s perhaps strange about these statements is that these institutions know the risks - and Taiwan is only one of them - but still US financial firms plough money into China. To ask why, and to what end, we are joined by Anna Macdonald, a British investment manager with the firm Amati and a seasoned media commentator on the markets.

Some highlights from our discussion:

Up until about two years ago there was plenty of Western enthusiasm for investing in China, thanks to belief in the opportunities there.

There have always been concerns about investing in China - for example, the challenge of getting cash out of the country.

Now there is more investor anxiety, driven in part by the ESG trend; ESG though can be a blunt tool unless properly used.

Unfortunately being on the ground to check investments is not possible at the moment, making the risks higher.

You can also listen to the podcast on Apple, Amazon, or Spotify.

As always please do share, comment, and subscribe. We’ll be back next week with more What China Wants, analysing what the forthcoming Party Congress has in store for the world.

Many thanks for listening.

***

Here is the transcript:

Sam Olsen: Hello, and welcome to What China Wants with Sam Olsen and Stewart Paterson. I am going to read you a few quotes here that I've taken from newspaper articles over the last few months about the attitudes of banks, looking at investing in China:

23 June 2022, JP Morgan thinks the darkest days with China have passed.

9 June 2022, investment banks say it is time to get back into China, says CNBC.

31 January 2022, Goldman Sachs unveiled big plans for China.

So, Stewart, these quotes obviously show that there is still a lot of interest in investing in China. But as you have pointed out quite a lot in the podcast so far, and the newsletter before that, perhaps there are increasing risks to investing in China.

Today, we're going to be joined by someone who knows a lot about market sentiment about investing, not just in China, but in investing all over the world, Anna Macdonald. Anna works for Amati Global Investors, an independent specialist fund management business based in Edinburgh. Many of you, especially if you are an early bird like me, will know her as a market commentator for BBC Radio Four's Today, and Radio Five's Wake up to Money programs as well. Welcome, Anna.

Anna Macdonald: Thank you. And it's lovely to be here.

SO: So, I suppose Stewart, you are going to ask a lot of the questions here as this is much more up your street than mine. I thought I would just start off, if this is this okay, by asking you what's happened over the last couple of years, because I remember two years ago, when Alibaba was trading at USD 300 a share, there was still a lot of optimism about putting money into the mainland. But why was there that attitude? Why was there so much optimism about investing in China?

AM: Well, I look at this through the lens of the UK companies in which we invest in but from a broader point of view, I would say that alongside Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan, there was this tide of enthusiasm about riding a wave of this burgeoning middle class in China that were not only demanding goods from overseas and from Western companies that could provide them and perhaps build up supply chains in China to supply them, but also they were on a significant effort to try and boost their own domestic demand. And this is something that we thought that globally allocating investors got into that and kind of overcame any kind of issues that they had from an ESG point of view.

I always think it's quite interesting when you listen to Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan's podcasts about their general thoughts on the market, that they really do tread very carefully around discussions around China. That's probably because, as you say, they've invested a lot in their footprint there and they've tried to make investing in China, as kosher as investing in many other economies that we might perhaps know a little bit better or have more boots on the ground in.

Stewart Paterson: I was reading the other day that UBS, for example, have actually hired special editors for their China product to ensure that the verbiage that analysts use around sensitive issues is not deemed offensive to the authorities. So there's clearly quite a lot of self-censorship going on at the financial institutions, and obviously, there is a fine line between the way one couches and articulates an investment thesis and disinformation. Because at some point, you actually have to shy away from telling the truth to avoid offending the Chinese authorities, I would guess.

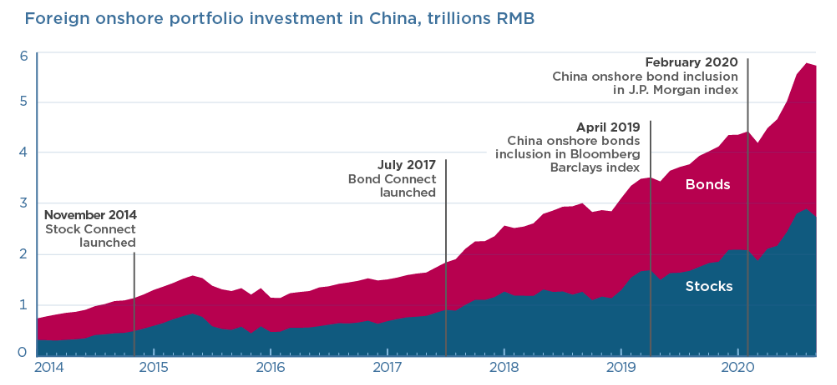

But I would say, Sam, I would just add that I think two years ago, there was a lot of optimism about the liberalisation of Chinese capital markets, that there were steps to induce foreign investment into the bond market directly, for example. And that prompted a huge swathe of reports and opinions from pension fund consultants, as well as big fund managers, pointing out the obvious that China is a large part of the global economy and a very small part of global capital markets, and that foreign investors were dramatically underrepresented in those capital markets. And therefore, you know, over time, there would be structural growth in those capital markets and investors had to get into it.

Anna, how would you describe the journey for those investors over the last two years? Because subsequent to that first wave of euphoria, we've seen some policy measures out of China - I'm thinking here of the sort of clamp down on the big tech and the Three Red Lines policy, which impacted the property companies - that have not exactly been investor friendly.

AM: Yes, I think you only have to look actually at how entrepreneurs - we talk about Alibaba, we have to think about how Jack Ma and others - are being treated to really reflect that even for homegrown entrepreneurs, there's been a complete change of attitude. I think that when you think about investments, you've got to think about the cost of capital of your investment. I would say that cost of capital has gone up, the risk has gone up of investing in China.

I think that it has become increasingly clear that as an overseas investor, you're almost a secondary investor. You become lower down the pecking order, should something go wrong, and actually, I think some companies have come to question how easy it is actually, for them to extract themselves for investment.

We invested in a company that had a cash balance in China, and when you actually talk about how you get that cash out of China, it is not nearly as simple as you might have thought; they can pay themselves a dividend out of China, but they can't actually just take everything out that they want. So, we cannot look upon that cash as being true cash, it's not freely available cash in the truest sense of the word. So those kinds of things have started to make people realize how much of a different environment it is, how authoritarian it is, and who the main person in control is, which is often not who you might think.

That has been overlaid by the crackdown on COVID that they have had, and the slower economic growth that they've been delivering - I think the World Bank this week reduced their expectations for GDP growth from 5% to 2.8%. That's also made it clear that perhaps things aren't going quite as swimmingly as the numbers might suggest. And I'm sure, Stewart, you would always think that you take those GDP expectations that China give you with a massive pinch of salt anyway?

SP: Yes, it's interesting because clearly, one of the things that differentiates China from any other investment - just purely looking at it from the economic side, rather than any ESG side - is the opacity and the lack of information, which you have alluded to. This has been known for a very long time, and when the focus in the tech companies suddenly re-emerged on variable interest entities as an example, and the fact that, foreign shareholders didn't actually own shares in the operating companies – they own shares in a company that had a series of contracts with the underlying company was a work around to, to basically break Chinese law.

That's been known, but of course, there's nothing like a cyclical downturn, to focus people's attention on the negatives, however well-known they were before. I suppose, wearing your ESG hat - which I know that you're very passionate about - when we look at this sort of sea change that is taking place amongst portfolio investors in China, as they've sort of metaphorically have had their heads handed to them, in terms of the financial losses that they've taken, is it possible to disentangle the two drivers of this change of opinion?

On the one hand, you have the pure economic loss that they've taken, which no one ever likes. But on the other hand, my sense is that people have become more aware and more alert to the ESG implications of investing in China. I'm thinking here of the UN reporting on Xinjiang, for example, where it's getting harder and harder now to ignore that and just dismiss it as rumour and hearsay.

AM: Yes, well, I spoke to a very small company in the UK that provides promotional goods and so on to big brands, such as Google or British Airways, and various big brands. And a lot of promotional goods, as you can imagine, are things like the coffee mugs, and the pens are sourced out of China. The primary aspect now when they're signing contracts with these big companies is: “we cannot have a scandal on our hands; these goods must come from proper manufacturers”. And they have invested a lot now at having people on the ground there who are able to check the supply chain, check the first-tier manufacturers, the second-tier manufacturers and that's giving them an absolute competitive advantage against some of their competitors because of the risks that these global brands face.

Brand names want to make sure that they aren't being associated with any contentious areas, whether that's the Uyghur Muslims or poor environmental practices and things like that in China. So, as I say, having people on the ground and being able to investigate those supply chains is seen as a significant advantage.

SO: So, Anna, just picking up on a few things you said in the last few minutes, what is fascinating to me, as someone who's worked in China for a long time, is that many of the things that you've mentioned have been things that needed to be worried about for a long time, for example, getting money out of the country. I've had many clients over the years who've complained about the fact that they've made money in China, but what do they do with the cash? Getting it out and repatriating it has been a challenge for a long, long time.

And then the issue around the Uyghurs and other potential human rights issues within China, whether it's prisoners, or whether it's huge amounts of people that are executed each year, obviously, that's different now than it was a while ago. But the fact is, is that all of the things come together and making it a difficult place to look at from a business point of view, if you want to take into account all of the ethics that the West demands of its own companies. So, my question is, if these things have been an issue for a while, why is it only now that companies are beginning to make a fuss about it, in the sense of actually changing their investment strategy to deal with China?

AM: I think it's because from an investor's point of view, so many more dollars are flowing into ESG style funds. Now, I don't think that the way they screen their investments is altogether the right way, we do it quite differently at Amati we do it very much on an individual basis. We look at the Freedom House score. So basically how free a country is to express the free press and to express their points of view, because it’s inversely correlated with how autocratic a country is. So the freer country is, the higher the Freedom House score, the more likely to be more democratic it is.

So, we think that's a very powerful way of looking at whether the people in that country are actually getting the benefit of the investments, or, for example, for a resource rich country, will those riches likely flow down to all citizens? It's pretty much true that the less democratic a country is, the less this is likely to happen, that the mass will benefit. So, that's just the way we look at ESG investment. But there are many more ESG dollars, there are companies that want to be seen as ESG, they've got to show improving scores and various different metrics. So that so by paying more attention to it, they can show that they're doing that and they will then show often it's the Delta, it's how much are you improving on your ESG score that makes that can drive investors.

The other aspect is that companies are now seeing that there is an economic advantage to be gained to providing alternatives. Whether that's alternatives sourcing of goods and services that's outside China, so that companies can de-risk their supply chains, or it's that they can see - as I mentioned with that company earlier - they can they can show their investment in making sure that their supply chains are clean, that they can therefore have an economic advantage in doing that whether they can charge higher prices and deliver better margins or however it is. So, I think those are the those are the main factors behind that.

SP: One of the interesting things you alluded to there was the difference between your approach and maybe other people's. Some of our listeners, I think, will probably be confused by the fact that there doesn't seem to be any standardisation as to what constitutes an ESG friendly investment. So, who is making up the rules and setting the standards? Is there a framework emerging, a standard setting body that is accrediting a fund, or certifying it and saying, that these people follow best practice in selecting their investments from an ESG perspective?

AM: There are several different screening services that you can subscribe to. Even if you have something like a Bloomberg or Reuters terminal, you can subscribe to these additional layers of screening, and they can give you scores for each aspect.

We very much drive our own process and our own screening because we think different things are important. For example, if I tell you that that shortly after the invasion of Ukraine, Refinitiv said that Rosneft and Gazprom had higher ESG ratings than Serica, which is a UK based company providing about 5% of the UK’s natural gas. Now this makes absolutely zero sense to us, that investing in Gazprom was somehow better from an ESG point of view than investing in something that was going to domestically ensure our own gas supply.

So, there are a lot of contradictions in the way the ESG screens are run and often one ESG provider will give quite a different score from another. But the main factor for not only thinking that we could do it on a more thoughtful basis, but most smaller companies are not really even covered yet by these screening factors. So, it was essential that we developed our own model for it. Bigger asset managers have huge departments doing this, and they will work alongside the analysts on individual stocks, and they will often still use a lot of these screening services.

So no, there's no definitive approach to it. And I think that's probably the right thing, because it means that you do have to consider each company on its on its own basis. I am sure that there probably are index funds that just overlay an index with an ESG score. But I would argue that this probably isn't going to drive the best forms of allocation in a thoughtful ESG-focused way - or "ESG H" we call it, with H meaning human capital. They won’t drive quite the right outcomes.

That was seen in earlier this year, when I received an email from Jeffries asking if I wanted to join a call listening to their experts talking about whether defence stocks were now the new ESG holding. Most investors had shied away from defence stocks and then realised that perhaps it was quite sensible to be able to protect your own country first. So, it's a tremendously complicated area. And it's got lots of different views in it. There have been huge developments in it, huge strides forward, and you can understand the motivation of a lot of the ESG funds. But at the same time, we know that there's been quite a lot of what we call “greenwashing” with companies or funds saying that they are very much focused on ESG. It is sometimes just seen as a way to charge slightly more on your fund management charge because you say you've got an ESG overlay. We've seen quite recently that Morningstar has slashed the number of funds that they describe as properly sustainable, and that's, that's quite interesting in itself.

SP: So Anna, that's very interesting about the ESG standards and what have you, but when you're looking at potential investments and looking at companies to potentially buy stakes in, are you seeing an increased amount of evidence to support the What China Wants view that the global economy is bifurcating along ideological lines between China and the West? Is that something that's a concern for corporates and are you seeing action on that?

AM: Yes, we are actually. There is a company that floated on the UK stock market about 18 months ago. It is based really out of Toronto, but they felt that a UK listing would be of benefit, get them good visibility. They license IP for chip design. And we all know how important the market is for semiconductor chips, and the demand for smaller and smaller chips is growing ever greater. And this company is right at the front end of designing the smallest three/four nanometre chip designs.

They had a joint venture in China, as well as having their Toronto base. And they felt this gave them a foot in both camps really, that they would be able to grow their business in the US and Europe, as well as benefiting from China, where we all know that they've really wanted to be able to grow their own semiconductor capacity on the mainland. However, Alphawave raised quite a lot of capital, on flotation for acquisitions, and they found a good acquisition in the US called OpenFive. Now, this meant it had to go to approval. CFIUS is the US regulator for that, and they have approved the deal. But it means ultimately that as part of the approval their JV in China will have to somehow be extricated from. And this really is something that has their view in terms of the opportunity that they would have in China, they will fully admit since flotation has meaningfully changed. And they would also say that it's interesting for them that Chinese companies in return do not want to be so reliant on Western companies.

So actually, it is something that's coming to a kind of natural conclusion in a way, but something that very much has changed over the last 18 months. I think that companies really are assessing their exposures in all sorts of different ways. Another example, I suppose I could give us a is a small company listed in the UK. It makes spectacles and lenses, and it kind of wants to become the next Essilor Luxottica. Most spectacles, I think it's around 90% of components come from China. So, it's a hugely, hugely efficient supply chain. And so, what this company is doing is urged by its customers such as Specsavers, and Boots, and Grandvision in the US, they are really ramping up capacity in Vietnam, and actually now in Portugal to try and diversify away from those supply chains. And it's being given really high priority by those, those big opticians, those big chains.

SO: So, one of the things that I would ask is - looking at our research on the complexities of global supply chains - it is all very well just set up new facilities in Portugal, but where do they get their inputs from? Are all those inputs coming from China? So therefore, an effect you haven't really diversified away from issues that could occur on the mainland?

AM: Absolutely. I mean, that is still some of the main issues is that the components do still come from China. So, they need to start thinking about not just the final steps of the manufacturing process, but then thinking about the components that are going into that. So yes, it is a big issue. The problem is that China has built up hugely efficient supply chains. Okay, they may have been a bit logjammed over the last 24 months, but those supply chains are very difficult to replicate. So, this is not an easy fix. Whilst we might think that nearshoring or “friendshoring” is going to provide the answers, I would say, we've hardly begun the process.

SP: Anna, thank you very much indeed for joining us today and giving us your insights. It's particularly useful, I think, for our audience and ourselves to hear the anecdotes from the front line as it were, as to (you know) what corporates are facing in their struggle to diversify away from China. So, thank you very much, and that's all from What China Wants and we'll be back next week. Thanks very much.

Episode 20: An Investor's Perspective on China