Hello and welcome to Episode 17 of the What China Wants podcast.

It is a sombre week for most people in the United Kingdom, the 14 countries where the late Queen Elizabeth II was Head of State, and the wider Commonwealth. But the impact of the monarch will be felt in other nations around the world too, not least the United States, whose embassies and military bases will fly their flags at half-mast by order of the President until after the royal funeral.

China may be a century-old republic, and a communist one at that, but that doesn’t mean its rulers can ignore the sad passing of perhaps the most famous woman on the planet. In today’s episode, Stewart and Sam pay tribute to the effect the Queen had on Sino-British ties, and look at how her position played into the wider historical narrative of what was, until 1911, one of the world’s oldest monarchies.

Some highlights from our discussion:

The Queen’s 1986 trip to China was a tipping point in Sino-British relations

But the 2015 visit by Xi Jinping, hosted by Her Majesty, revealed some of the cracks in the so-called Golden Age between the countries

Modern China’s relationship with monarchy is complicated, but still relevant

King Charles III’s more forthright views on China may be notable, but it is probably the new Prime Minister Liz Truss who will prove to be more pivotal in future relations between the countries

You can also listen to the podcast on Apple, Amazon, or Spotify.

As always please do share, comment, and subscribe. We’ll be back next week with more What China Wants.

Many thanks for listening.

***

Here is the transcript:

Sam Olsen: Welcome to What China Wants in this very important, and for many people, sad week, with the passing of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. Stewart and I thought it would be appropriate to talk about the life of Queen Elizabeth and her relationship with China. As some of you will know, the relationship between the monarch and the People's Republic has been incredibly important in building up relations between the entire United Kingdom and with China over the last 40 or so years. And so, it's entirely fitting for us to discuss that relationship, but also to look perhaps more widely at China's relationship with its own monarchy, and to see what that means for China's position and China's posturing today in the global world.

It is fair to say that the death of the Queen has not gone unnoticed by China. In fact, very soon after the official announcement of her death, President Xi Jinping sent a message of condolence to Charles III, over the passing of his mother, which said, "On behalf of the Chinese government, and people, as well as in his own name, Xi Jinping expressed deep condolences of the passing of Queen Elizabeth II, and extended sincere sympathy to the British Royal Family, government, and people."

And Stewart, who joins me as always, this is quite an important time in international relations with the death of the Queen and moving into a new era in the UK, but also probably can be thought of as an important moment in international relations full stop, including with China, wouldn't you agree?

Stewart Paterson: Very much so indeed, and I suppose my question to you, as someone who follows Chinese society closely, is what did the Queen mean, if anything, to the Chinese people en masse, as it were, and what has been their reaction as far as you can glean from the Internet and other sources, to her passing?

SO: Well, I think it's fair to say that the majority of people in China won't have any feelings for the Queen one way or the other simply because most of them don't really have much of an international viewpoint, given China's history. And I think that those that do have thoughts on the Queen, especially those who are quite patriotic, many of them will look at the Queen in a very positive light, given the impact that she had in her first visit in 1986, which was a couple of years after the British signed back Hong Kong to the mainland. The reason for the visit was to cement ties and to bring ties a bit warmer than they had been because of the break since 1949. And in that, she succeeded fantastically.

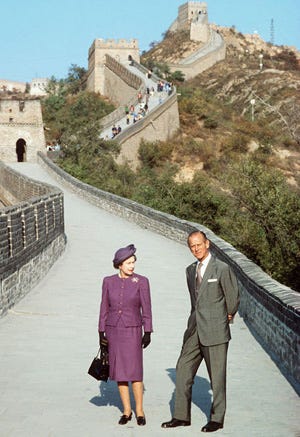

I have met Chinese people who were around for the visit. In fact, I had a long drink once with Deng Xiaoping's official translator, who was in the room with the Queen and others during that visit. It was very clear from his point of view that the visit had been a massive success, Deng thought very warmly of her, so he said, and thought that everything had gone swimmingly in terms of boosting both British and Chinese ties, but also adding a bit of stardust to China, which, bear in mind, was still coming out of the doldrums from the Cultural Revolution. For the Queen to go, I think it meant a lot to people. And there are lots of funny stories about trying to find the right accommodation in Guangzhou because there were not any hotels in the city at the time. Apart from Guangzhou, she went to a number of the cities including Xi'an, Shanghai and Beijing, etc. In Xi'an, there's that famous photo of her - my favourite photo of the tour - which was of her meeting the Terracotta Warriors, looking quite faintly amused by being surrounded by such amazing artefacts. But the most important parts of the set was the fact that she was able to really invigorate Sino-British ties, and to show that Britain's establishment did want to have a relationship with the PRC.

SP: So obviously, there was that official visit to China. But in terms of public reaction to her death, I think here particularly maybe in Hong Kong rather than mainland China, is there any significance to what we're seeing, what are we seeing, and how does that sit with Chinese officialdom, given the frequent accusations of foreign meddling in Hong Kong, and the supposedly separatist movement that emerged in Hong Kong in recent years, and the democratic movement that emerged in Hong Kong? Is there a sense that there's a sort of misplaced allegiance amongst some segments of Hong Kong society to the United Kingdom, and that the Queen was in any way emblematic of that?

SO: I think you hit the nail on the head. There will certainly be people within the Communist Party within the senior Chinese officialdom, who look at the outpouring of support and memory for the Queen in Hong Kong as being perhaps troubling in an anti-patriotic type of way. And there certainly has been a lot of thought about the Queen. My friends on the ground were telling me that the line to sign condolences at the British Consulate in Hong Kong was at least a kilometre long for much of the last few days.

And there are a lot of people there who look at the Queen as being emblematic of better days. Whether you agree with that or not, there are still many people in Hong Kong, who think that the colony was the height of Hong Kong's life rather than what happened post-1997. Although perhaps many of those are living in the UK considering the success of the BNO passport scheme. Still, there are people in Hong Kong who have a favourable view of Britain and the Queen awfully embodies what Britain stands for.

That perhaps is the dividing line, because there will be people in China who also perhaps don't like to think about the Queen, because they also think that she embodies Britain, and with relations cooling significantly because of Hong Kong because of British discussion around the treatment of the Uyghurs, perhaps also because of Huawei, Britain is not massively popular amongst some segments of society in China. And of course, those people won't be particularly happy about anyone in the country celebrating something that they think, is a foreign ruler, and a foreign ruler from not a friendly country.

But Stewart, I suppose that's all very well, but it's not just talking about the past, we're also talking about the present and the future, we have a new King. And there are perhaps issues in King Charles' past around his views on China, that perhaps won't sit too easily on the shoulders of those people that we just mentioned, that aren't particularly fond of the UK and the British Royal Family standing for what we stand for, what's your thoughts about Charles’ future there?

SP: Well, of course, having spent so much of his adult life as Prince of Wales, and in doing so enjoying a relatively high degree of freedom to express views on issues, and Prince Charles has not been shy about doing so, we know more about his personal opinions on a number of subjects than we did about the late Queen. Two of them spring to mind. King Charles is obviously a man of deep faith, and has over the years struck up a meaningful friendship with the Dalai Lama. That, obviously, must be a cause for concern for China in the sense that the Chinese see the Dalai Lama as a separatist threat, and the whole issue of Tibet, and their occupation of the ‘country’ is clearly a thorny issue for them. The other issue, of course, is King Charles' deep concern for the environment. More recently, Charles has made it abundantly clear that in his view, a global solution to the climate issue is unobtainable without the cooperation of China. Therefore, China has to be an integral part of that solution.

We also know from the handover and the privacy court case that stemmed from the leaking of his private diaries of around that time - we're going back now to the 2006 privacy case against the Mail on Sunday - that the then Prince Charles had some fairly forthright things to say about the Chinese regime. The two things that spring to my mind was his comparison of their behaviour to the Soviets. I'm referencing here, the shadowing of the royal yacht, Britannia, in the South China Sea, and protocols in the run up to the handover. And so, I think it is fair to say that from what is publicly available, the new King has, in the past at least expressed severe reservations about the Chinese regime. And clearly his respect and understanding of Islam will not sit well, I suppose, with the accusations against the Chinese regime and their treatment of the Uyghurs, which obviously have been boosted by the recent United Nations report, which seemed to verify a significant number of the accusations that have been levied at them, even if perhaps if it came up a slightly lighter on detail than some of the other investigations that have gone on to look at events in Xinjiang.

So, what does that actually mean, though. for Sino-UK relations going forward, and I think it's probably fair to say that it's a bit of a sideshow, in the sense that, Sino-UK relations, as they stand at the moment, are on a very different footing from the time when, under David Cameron, Xi Jinping made his state visit to the United Kingdom. So, I'm not sure that the change in monarch is going to make a significant difference to Sino-British relations.

SO: What probably will make more of a difference is the fact that you have got Liz Truss, who is much more of a China hawk than previous Prime Ministers that have held the position. But I think that one of the things that's worth noting is that it's not just about what China thinks of the UK when it comes to the monarch, but also how we view China through the lens of the monarch. That 1986 visit, I think, was really instrumental, I remember it quite well. I've always been interested in China and the fact that there was the monarch going there did enliven my interest.

But when in 2015, Xi Jinping came, sort of at the height of the so-called golden era, I think, it was very interesting to see how there was actually quite a lot of pushback against some of the behaviours of the Chinese officials, those organising it, who were apparently incredibly obnoxious to their British counterparts, including threatening to walk away and cancel the visit if they didn't get exactly their own way. Secondly, the security officials who undermined and even bullied some of their British counterparts, especially if you remember the men running alongside Xi Jinping's car during the visit. The Queen made clear that she wasn't happy when she was overheard saying that Chinese officials had been very rude. And for me, watching that, I remember thinking, 'Okay, so the Queen generally is one of the most secret and dependable of guests and of hosts. For her to say something, it means that she must have been really ticked off with what was happening.' And I thought, does this golden age that Cameron and Osborne want to have really exist in depth in the Establishment and across Britain? If you see the Queen, who's obviously incredibly loved, pushing back and saying that the Chinese have been rude, that didn't necessarily bode well for Sino-British relations.

So, you are right, I don't think it's the be-all and end-all having a new King in seeing how we're going to live with China in the coming years. But I think it is still interesting as a reflection on general ties between the countries.

SP: And I suppose you could say, Sam, that in a way, those sorts of complaints, be they relatively minor in the big scale of things, could be interpreted as indicating that the Chinese behaviour is being interpreted as a not a meeting of equals, that when their own leader was coming to the United Kingdom, that there was a sort of Sinocentric approach to the trip, and that it was our privilege to have him as it were, as a guest, as a sort of a lower ranking tributary state. Not quite, but that sort of cultural superiority, perhaps impacting the behaviour.

SO: Yeah, it could be. So that begs the question, Stewart, when you' have a monarchy in China, that goes back to well, actually, the mythical first Emperor of about 2500 BC, which is approximately when Stonehenge was being built. That's a long time and the first official Emperor of China, Qin Shi Huangdi, who ruled from 221 BC, that's a long time to have a monarchy, and the monarchy eventually went, officially in 1911 with the revolution then, as told in that film 'The Last Emperor of China', as many of you will have seen

But Stewart, going back to your comments there about perhaps China using that trip to look at us as a bit of a tributary state, does Xi Jinping himself come across as an emperor? Is he in fact, a new emperor or an emperor in new clothing?

SP: I suppose the argument for that is the centralisation of power. And of course, our own monarchy has been massively diminished in its power and its authority and is really a mere figurehead with a sort of formulaic constitutional role to play. In China, of course, they are sort of slightly going the opposite way in terms of the concentration of power, and with that power, of course, comes responsibility. And the whole centralization of the decision-making process, the ideology behind it, and in Xi's case sort of Marxist-Leninist ideology does not necessarily produce good decisions.

I think we're seeing, for example, in China, something I was reading today about the employment prospects for people who've studied Marxism in China are improving substantially, to the detriment of those people who've studied mathematics or science. So what we're seeing is a kind elevation of ideological purity in China to the detriment of the technocratic brilliance, which many people ascribed China's success to, the emphasis on technocratic competence in the administration.

So is Xi an emperor? Well, he's certainly, in some people's view at least, is behaving more and more like one. But Sam, as you know, from the history of China, the mandate from heaven can be removed. And the usual reason for that in history, of course, has been flood or famine. But the modern-day equivalent of that, I guess, is economic failure. And clearly at the moment, things in China are not looking brilliant on the economic front. Of course, there are many other challenges as well, environmental challenges, demographic challenges, etc, which are structural in their nature.

SO: And droughts, as we recorded last week! That's a significant issue, I think, in the minds of the bureaucrats in China as well, the fact that they have got this huge drought, which, as you said, has been historically very much linked to the decline of dynasties.

SP: Well, that's what I was going to ask you, Sam was, if you look at the sort of history of regime change in China, which I know you know, a lot about, am I right in saying that economic failure, be it through natural disasters, or through manmade bad policy-making has been a crucial part in bringing about the fall of emperors?

SO: Yes, it definitely has been. There are between 13 and 26 dynasties since the first emperor, depending on how you count a dynasty, and the death of almost all of them have been accompanied by some kind of natural disaster, but often through foreign invasion as well, for example, the Manchu for the Qing Empire, and so on.

But there is something quite ironic about what you just said about the concentration of power because, one of the successes of the British monarchy and European constitutional monarchies across the board has been the fact that they have allowed over the last couple of 100 years, their powers to be taken away and concentrated in elected representatives, who at the end of the day, carry the can for mis-steps. And there is something slightly problematic, I think, if you want the success of the Chinese Communist Party to continue for a long time, in Xi Jinping, bringing lots more powers and responsibilities into his own grasp, because obviously, if and when things go wrong, and things always do go wrong, then it becomes easier to blame him.

It is slightly worrying when you look at China through that lens because no one wants China to experience sort of some of the upheavals of dynastic change that they have suffered from in the past, where literally millions and millions and millions of people have died. Obviously, no one wants that. But Xi Jinping, I suppose at the moment, as we have spoken about many times in this podcast, is looking at how to keep political primacy rather than economic primacy because the CCP after all is a political, not an economic, organisation.

But if we look at where things can go falling short of dynastic change, the Cultural Revolution from 1966 to the mid 70s. And that was exemplified by the Red Guards going around and causing huge problems getting rid of the olds, destroying artefacts, and one of the things that they destroyed, which is kind of ironic, considering we're talking about Queen Elizabeth II, was the tomb of the Emperor Wanli, who died at about 1620. He and his Empresses were dragged out by the Red Guards and burned.

Now the interesting thing is from a historical point of view is that when Queen Elizabeth II went to China, in 1986, as I mentioned she gave the following speech, which obviously showed off her humour, but also a sense of history at the same time. It went like this: "Some 390 years ago, my forbear Queen Elizabeth I wrote to the Wanli Emperor, expressing the hope that trade might be developed between England and China. The messenger met with misfortune, and that letter never arrived. Fortunately, postal services have improved, and your message inviting us here arrived safely. And it has given me great pleasure to accept it."

I'm not sure who wrote that speech for the Queen, but whoever it was recognised the importance of the Wanli Emperor having been cut out of his grave, just 12 years before that speech, and burned by the Red Guards. I'm pretty sure that they would have known that had taken place, so what the message they were trying to get over is interesting.

I think at the end of the day, Xi Jinping doesn't want to be called an emperor, but his position at the top will be considered by many to be that of an emperor. And the fate of Chinese emperors was good for as long as the good times lasted, and he knows that better than anyone else.

SP: I believe, Sam that one of the trending posts on Chinese social media was something along the lines of 'he who should have died didn't'.

SO: That's not going to go down well with the censors at all, but I think a lot of the other posts on social media, as our colleagues have told us, have been very positive. In fact, isn't The Crown trending again, I think on one of their media databases or Netflix streaming-type equivalents? So obviously, there was a lot of thought about the Queen from the public at large, but the political ramifications and the political imagery surrounding the Queen are certainly things that will be noticed by the Communist Party and not ignored.

SP: Thanks, Sam, that's very interesting. And Sam and I will be back next week with more What China Wants. Thanks very much. Bye.

Thanks for reading What China Wants by Sam Olsen! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Episode 17: The Queen, China, and Imperial Monarchy