Hello and welcome to Episode 15 of the What China Wants podcast.

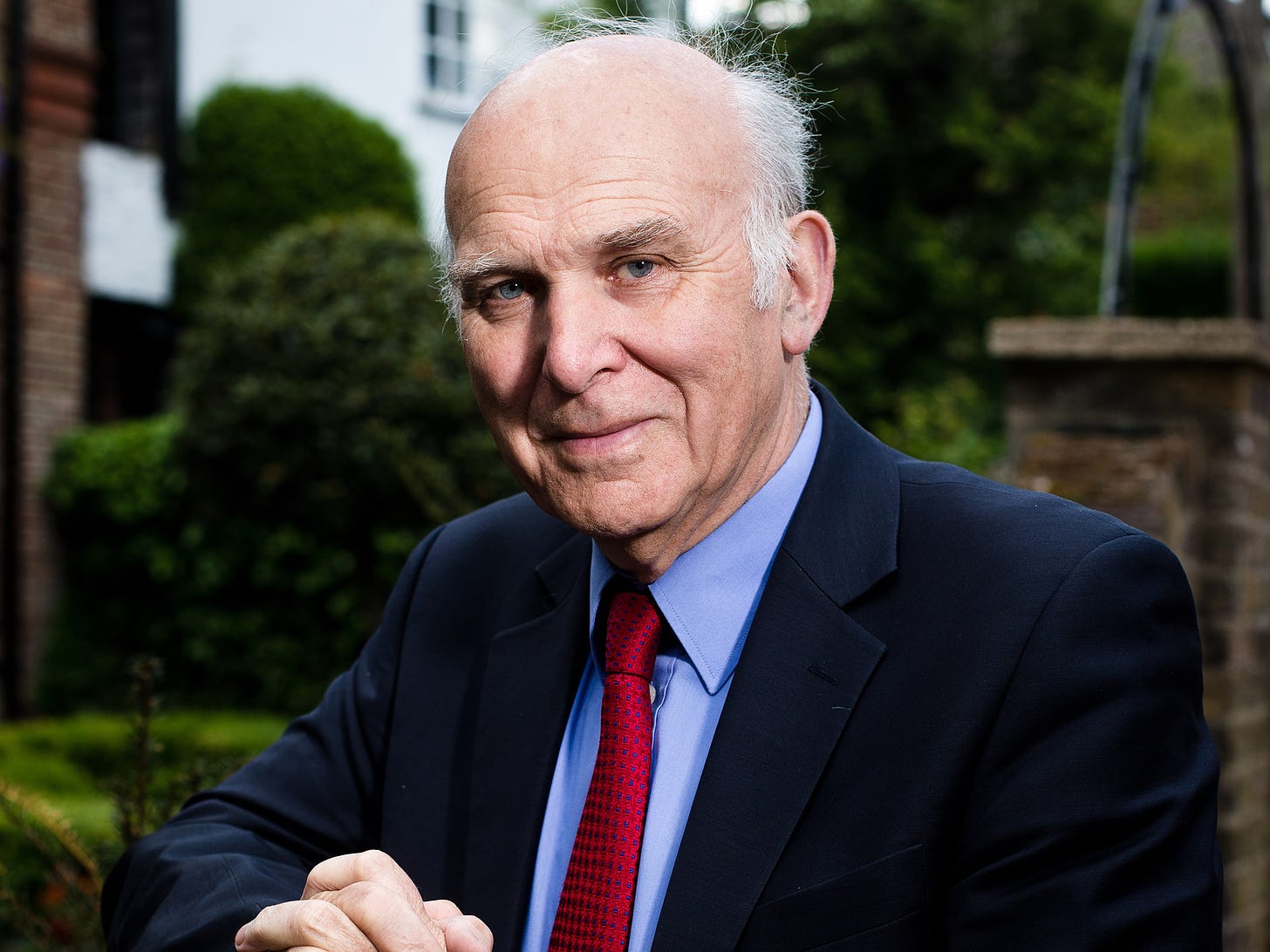

Western liberalism is not the force it once was. The question is, to what extent is the authoritarian model espoused by China and Russia pressuring and ultimately dimming liberalism’s star? To answer this we are joined by Sir Vince Cable, former leader of the UK’s Liberal Democrats and a senior minister in the 2010-2015 Coalition government.

Some highlights from our discussion:

The West used to hope that China would liberalise, but these hopes came to naught

There is a question as to whether China’s economic rise has been good for the West (and therefore potentially liberalism) in any case

There are a number of reasons why liberalism in the West is under strain, including the 2008 financial crisis and the failure to export democracy

The future is not necessarily one of conflict between the systems of China and the West, but to stop this potential conflict a lot of effort needs to be put in

You can also listen to the podcast on Apple, Amazon, or Spotify.

As always please do share, comment, and subscribe. We’ll be back next week with more What China Wants, discussing China’s chronic water shortage and what this might mean for the country and the world.

Many thanks for listening.

***

Here is the transcript:

Stewart Paterson: "By joining the World Trade Organisation, China is not simply agreeing to import more of our products. It is agreeing to import one of democracy's most cherished values, economic freedom. The more China liberalises its economy, the more fully it will liberate the potential of its people, their initiative, their imagination, their remarkable spirit of enterprise. And when individuals have the power, not just to dream, but to realise their dreams, they will demand a greater say." That, of course, was Bill Clinton in his 2000 speech to Congress, in the run up to China's accession to the World Trade Organisation.

Hello everyone, and welcome to What China Wants. My name is Stewart Paterson, and as always, I'm joined by Sam Olsen. Hello, Sam.

Sam Olsen: Hello, Stewart.

SP: Well, Sam, perhaps you'd like to introduce our very special guest today?

SO: Thanks Stewart. Sir Vince Cable, I think, knows more about international relations and about Western liberalism than most people listening to this podcast, having been a staunch bastion of Western liberalism through the Liberal Democrat Party in the UK for many, many years. He has recently written a book about China (The Chinese Conundrum), which we're going about today.

But before we do, a quick bio for those of you who don't know him (because the majority of our listeners are from abroad these days). Sir Vince Cable was a Member of Parliament between 1997 and 2015, as well as deputy and full leader of the Lib Dems. During the 2010 to 2015 Coalition Government Vince was the Secretary of State for business innovation skills and the President of the Board of Trade, working alongside my old boss, Theresa May. Before that he was the chief economist of Shell globally before making the move into politics.

So Vince, with your knowledge of China and your deep experience within the Liberal Democrat Party, what we want to do in today's podcast is to explore Western liberalism, and to talk about how China is impacting that. But before we do that, I suppose we better find out from you what your definition is of Western liberalism.

Vince Cable: Well, I think it's complex, it's multifaceted, I suppose it would start for most people with the western concept of human rights, which is about individual liberties, freedom of expression, freedom of thought, freedom of worship, and at times various other things shared by people who are not liberals necessarily. There is also belief in the rule of law, belief in democracy, which aren't exclusive to liberals. And also for some people an attachment to the idea of self-determination for minorities, which I have rather ambiguous feelings about, but for many liberals this has been quite an important principle. I think the central one is individual human rights, freedom of expression, individual liberties.

SO: That's very different to the authoritarian model espoused by China and Russia and other states. How difficult is Western liberalism, finding it in the face of a rising international regard for authoritarianism, as pushed by China and its allies?

VC: Well, it's I think it's always been a difficult issue that it's been subordinated to other commercial and geopolitical priorities. But if we go back to Tiananmen Square there was a great expression of outrage amongst liberal minded people in Europe. And then in the United States, Bill Clinton, when he first became president was put under a lot of pressure to strengthen the limited sanctions that had been introduced by George W. Bush. There were two arguments which prevailed at that time, and are now less compelling or less believed. The first was the idea that, “Nevermind, it's authoritarian at the moment, but maybe with opening up and more freedom of movement, free trade and the rest of it, China will become less authoritarians as a sort of expression of hope.” And of course, that hasn't happened. The second was the argument that prevailed with Clinton himself, which was the view that “it's the economy, stupid”, the idea that we may not like what we've found in China, but China's a major economic player is going to become even more important. We need to engage we need to trade in our own self-interest.

There were very powerful ties between the United States and the manufacturing sector and the big banks in Wall Street, all of whom argued the economic case, which prevailed with the Clinton administration who persisted with WTO admission. And I think there's been a similar sort of dynamic in Europe and in the UK. A lot of people wanted to believe that China would liberalise and even if they didn't, they accepted that there was a very powerful Western self interest in engaging with China economically.

SP: Perhaps I can ask you a little bit about that economic engagement, because the trade relationship certainly has been decidedly asymmetric for almost all countries. I mean, Germany is a bit of an exception in the sense that it itself has a very entrenched sort of industrial policy, that the Chinese, in fact, mimicked large parts of the German and Japanese and Korean models of economic development when they were looking around for sort of role models for their own economic liberalisation process.

But that asymmetry has been borne out, and the arguments put forward by the commercial lobby that the commercial opportunities in China were so compelling that they could not be ignored has now somewhat backfired. This is because of China's perennial current account surpluses, and the fact that China seems incapable of boosting domestic demand to a level at which it absorbs its own supply. Would you agree?

VC: Well, I think if you take a rather than mercantilist view of trade and look at bilateral imbalances, it's certainly the case that China is less attractive as a trading partner than would otherwise be the case. I don't take that view, and I think a lot of business people don't take that view, they take a wider view, let's say in the case of the UK, with that there may be a bilateral imbalance, but there is a fair amount of inward investment from China, increasing amounts that has proved useful. It's not massive, but have some advantage.

And we've encouraged China in the same way that we encourage Japanese investment in the 1980s. There's a substantial amount of UK and other Western investment in China with some of which has proved highly profitable. And the profits have fed back into reinvestment here. So there's this kind of wider view of relationships. And it isn't just about trade imbalances.

There is also the view that the Chinese economy has become just so massive, and the massive nature of the Chinese economy means it's lifted the world economy as a whole, particularly commodity exporters. So if you take a wider view, of economic gain and loss, then the Chinese have been good for the world, and that may not be changing. But certainly the view that China is a big player and should become encouraged to open and for us to engage more with them, and argue the case for more liberalisation of trade and investment, is one we've all been carried along by that. I think actually they are not stupid or naive arguments. In many ways, China has had a very positive impact on the world economy.

SO: One of the things we've discussed in detail in the last few minutes is economic liberalism. But to what extent is that intertwined with social liberalism? If we start off by looking at the UK and the West, in your experience, to what extent is economic and social liberalism entwined?

VC: Well, it was one of the great hopes of Western liberals in general. I mean, going back to Fukuyama and the defeat of communism, that somehow or other the world was becoming a haven of liberal democracy and both political and economic. And I think we realised that actually this was wrong, and that there are many countries for whom the adaptation of democratic institutions has become very difficult. We've seen regression in Middle Eastern countries, Turkey would be a good example, Egypt too, probably other countries which have become very rich but which haven't developed any kind of appetite for democracy at all. For example, the Saudis and the Gulf states. We've seen cases in Asia which have some democratic elements but have also kept a model of political authoritarianism alongside economic liberalisation - partial liberalisation. And this has proved to work very well for China, and indeed for other places, too. I mean, Singapore is nominally democratic, that basically a one party state, very paternalistic, and very, very successful. Not liberal, in a Western sense.

SO: It’s interesting what you're saying, because there are some people who, of course, would say that you cannot have economic liberalism without social liberalism and vice versa. And this is perhaps one of the issues that we're seeing in the West is the decline in belief in the liberal underpinnings of a society, especially around democracy. There have been many polls over the last 10-15 years which have detailed the collapse in the belief in a democratic system, especially amongst younger people in the West – such as Australia, UK, and America. In fact, in Australian and American polls from a few years ago revealed that the amount of people supporting democracy have fallen to their lowest ever levels.

So with China in mind, do you think that there is a connection between this dismay about the positive benefits of democracy in the West and the rise of China? Do you this that democratic dismay is compounded or even encouraged by looking at China, Singapore and other countries, which don't have anything close to the democratic system that we do? Perhaps people say, “well, they're managing to do well, economically, so why do we continue and persist with democracy when it's actually not doing much for us?”.

VC: I think there are several reasons why the belief in liberal democracy which we have is no longer shared quite as widely as it was, sadly. One was the failure to export democracy, and then classically, the attempt to use the Arab Spring, and then before that the war in Iraq – this kind of evangelical Democracy had a bad story to tell. I think, secondly, crucially, the banking crisis introduced a big crisis of confidence in Western countries about their own capacity to manage. Our own experience in the UK of the collapse of the banking system, it may well have been well managed the crisis by Gordon Brown and my own government, but it was a shock to the system, and we've paid for it subsequently. And it's lead to a lot of cynicism and anxiety about the model we're using.

So those are two big factors. And then I think, the self-confidence of China about its own economy has an effect. But now we know that there are lots of problems in the Chinese economy, and is becoming more widely known with the problems of the property sector. The arguments with the big billionaire sector in China, it's not quite the model that we thought it was. But nonetheless, there is crumbling self-confidence in the West about its own ability to manage economic crises, combined with relative success in China and other countries which model themselves on it. I think these have all fuelled the scepticism about liberal democracy in the West itself. And then crucially, President Trump tearing up the rulebook showing complete contempt for the values of liberal democracy as further eroded self-confidence.

To my mind, a crucial issue is whether the European Union, which does put economic and political liberalism side by side, whether the European Union can hold the line and ensure that domestically within the Union, its values are upheld. I mean, we know that they're under attack from the Hungarians, in particular, to some extent, Poland. But so far, you know, the European Union has managed to maintain a belief in economic and political liberalism and to uphold those values, but it's hard work. And there are a lot of people who are pessimistic about that.

SP: The European Union has also been pursuing a policy of engagement with China and in fact has carried on pursuing it aggressively, even after the United States started to push back against some of China's practices, and drawing attention to its human rights abuses. But now the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment between China and the EU has been shelved and there is also shock about Russia. To what extent do you believe that the European Union is actually having second thoughts about this policy of engagement at all costs with China?

VC: Well, it clearly is having second thoughts. And the question is whether it swings too far in the opposite direction. I think the arguments for engagement with the Chinese were partly driven by German interests, but I think it was much more widely felt when Britain was in the European Union, we were very much part of that way of looking at the world. And it wasn't just trade narrowly defined, but large numbers of overseas strategy students who were thought to be very good for the economy. The French have done very well in China, luxury goods sector. Some other advanced manufacturing, the smaller countries, or perhaps less influential countries of southern Europe, Italy and Spain, have treated China in a very pragmatic way. Some of them have benefited from the BRI initiative, Greece, for example. So although there are mixed feelings about the Belt and Road, undoubtedly some European countries have seen benefits in it.

So the arguments for engagement were much more widely distributed than the German export sector. Now why is it being re-examined? Well, I think, partly human rights, the liberal group in the European Parliament has been particularly vociferous. And there is discomfort in the centrist liberal parties and the Social Democratic parties about what's been happening in China. So that's one factor. And I think another is deferring to the United States. The US is our major ally and provides support for NATO. It's perfectly understandable that European countries should not wish to be directly contradicting and undermining the position, the Americans have taken out that whatever the rights and wrongs of it, so I think there is a wish to defer to American sensitivities. Britain's 180 degree turn on Huawei is largely explained by that, and when there were worries they were considered perfectly manageable until the Americans made it clear that that was not an acceptable arrangement.

The war in Ukraine has certainly changed things even further in the direction of scepticism and one in a very direct way, because of course, the Chinese rail link with Europe crosses Russia. So both in terms of physical geography, and in terms of the open support that the Chinese have given politically to Russia, although they have been very careful in practice not to cross too many red lines on sanctions. But in terms of open political support, this has clearly alienated China from Western European countries. In summary, I think all those factors together, have added to a reappraisal.

I think some reappraisal, some correction, is necessary. My own personal view is that we're in danger of going too far in the opposite direction, and ignoring the importance of China, not just in trade terms, but in terms of international public goods - the whole climate issue, pandemics, nuclear disarmament, and so on. And China is crucial to those if not always completely constructive. I think people in leadership positions in Germany, particularly, but also elsewhere is that they're trying to develop a more balanced approach to China, but not to turn their back on it.

SO: Now, you mentioned a word earlier, pragmatic, and I've seen you use that word a few times in interviews over the over the last months. And I think one example you gave was that we have to be pragmatic with China in the same way that we're pragmatic with Saudi Arabia. Now, we don't necessarily like their human rights record, but we still deal with them.

Likewise, Stewart and I would say that there has to be a role for China in our international relations, in our economy, etc, because it is too big to ignore. The question is trying to find that balance. But one of the things that I think is perhaps a challenge to that is ESG. And there are increasing calls for China to be side-lined because of ESG sensibilities, particularly around the social and the governance, the fate of the Uyghurs and Tibet and other issues around potential slave labour etc. These all come to mind in investment. To what extent do you think that the rise in ESG concern is a reflection of classic liberal attitudes, or do you think this is just a new phenomenon that we are having to deal with?

VC: Well, I perhaps should be more of an evangelist for the ESG movement than I actually am. It may be that having worked for an oil company before I became an MP has slightly changed the view of the world in a more what I would call hardheaded direction, but it's undoubtedly an influence. And certainly the Uighur issue struck a lot of chords, and we can argue about how merited that was, but it certainly influenced a lot of people. I'm not sure about ESG itself. There are a lot of contradictions in it. Until very recently, ESG values tended to exclude companies that made armaments but in view of the Ukraine war, we are now very much in favour of armaments producing companies. And there are many other contradictions which exist in ESG. But clearly, you know that there is a group of ESG investors and indirect investments through pension funds and retail investors too. And there are young people applying to work for companies who do regard ESG values as important. China, unfortunately, doesn't take too many boxes in the ESG arena. But ultimately I wouldn't overstate ESG, I think most companies ultimately look to their bottom line. That's actually what their shareholders put their money in for, in terms of legal compliance. A lot of companies will continue to see good business in China. 20 odd years ago the company I worked for (Shell) worried about how the company's reputation would be affected by dealing with China. But actually, the relationships been very successful, there's been lots of reinvestment, a lot of good relationships with Chinese partners, and a lot of money has been made. And you could say the same for Jaguar Land Rover, for the pharmaceutical companies like AstraZeneca. So I mean, they will look at the ESG dimension, but I suspect in many cases, good business has been done in China, and they will not want to retreat from it.

SP: The big story of the summer regarding China on the political front has been Nancy Pelosi, her visit to Taiwan, and the People's Republic of China's reaction to it. Do you think that that visit was a mistake? Do you view it as a needless provocation? Or do you think that it's important for democrats to shine a light on the fact that Taiwan is an example of ethnically Chinese political entity that is democratic and highly successful?

VC: Well, I think it was a provocation. The question is, whether it was a sensible and justifiable provocation. I'd feel very much in two minds. I mean, in my Liberal Democrat heart, I'm very conscious that the ruling party in Taiwan is a member of the liberal International and genuinely shares its values; I've been to diplomatic receptions of my party where Taiwan is a welcome guest, which causes Chinese friends considerable upset. So on one level, it is clearly a country or entity (I'm not sure it's the correct word for it) which demonstrates liberal values to the nth degree and we should admire and support it.

On the other hand, I think any familiarity at all with the history of modern China knows that this has always been a very sensitive and ambiguous issue. And going back to Kissinger and Nixon, throughout all the engagement with China, there's been a clear understanding that there is no need to provoke the Chinese to recognise this ambiguous formula about one China but two different entities, and that we shouldn't needlessly stir up conflict over the assailant. The Chinese from my impression, have always been very pragmatic about Taiwan. Lots of Taiwanese coming backwards and forwards. One last time I was in China, I was given a guided tour of Foxconn in Guangdong, I think an enormous Taiwanese complex operating in China welcomed by the Chinese acknowledged to be Taiwanese, but part of the pragmatic relationship they've always had. Of course, it's not merely the fuel that's been thrown on the fire by the philosophy visit and similar things, but we have this tension about semiconductors and Taiwan's unique capacity for high capacity chips. This is a geopolitical issue, and I imagine that the Chinese primary interest is getting Taiwan to transfer as much of the technology as possible rather than to destroy it. The mindset is, I think, very different from the Russians. But yes, it's delicate. And I think there is a really difficult balance here to be strike between showing solidarity with Taiwanese democracy, and recognising that there are guardrails that we shouldn't be kicking over and provoking the Chinese on this.

SO: I'm looking at the time and sadly we have to wrap up, but I really appreciate you coming on Vince, it's very good to get a mind like yours which seen things come and go over the years. I just want to ask one final question. Do you think that Western liberalism and Chinese style authoritarianism can coexist in the years to come? Or do we think that we're in some kind of fight to the death?

VC: No, I don't believe in the fight to the death. In the book that I wrote, the Chinese Conundrum, the way I looked at the future was the way I'd been taught to look at it, when I worked in show as part of that scenario planning team, that you don't predict the future, you think about plausible stories about how things can work out. And certainly there is a story of the future, which I call in that book, The Sparta China scenario, which is going back to the Thucydides Trap which is very fashionable amongst geopolitical people in America. And it is possible that we could find ourselves in this desperate conflict situation, which could end up in war and nuclear war, but I don't think that's inevitable.

I do think that there is an alternative scenario, which isn't about being Lovey Dovey, and admiring each other’s systems. But it is about practical engagement of the kind that was pretty mainstream before Trump derailed in. And I think probably with new leadership in China, that will happen at some point or some rethinking of their position. We know there is quite a vigorous debate going on in the Chinese leadership about how to relate to the world. I think we could get back to that. But it does also require the liberal establishment in the West to understand that this probably is the only way to avoid conflict. And it may involve holding our noses, but engagement through trade and investment, but also through cooperation on public goods, climate change, etc. is necessary. And I'll stick my neck out and argue for it, though it isn't always popular and amongst my liberal friends.

SO: So Vince Cable, thank you very much for joining What China Wants. To end, your book. The Chinese Conundrum is available from all good bookstores.

Thank you very much, and Stewart and I will be back next week for more about China. Goodbye.

Episode 15: Is China a Threat to Western Liberalism?