Hello and welcome to Episode 11 of the What China Wants podcast.

One of the most important differences between China and the West is its language, and of course its script. That it is so impenetrable to most people outside of East Asia is unfortunate because together they say so much about the history of China and its place in the world today.

The story of the Chinese language and how it is written down (and has been for millennia) is fascinating. Here to discuss it all in our latest What China Wants podcast is Mandarin enthusiast and the author of the Slow Chinese newsletter, Andrew Methven.

Our main points from today’s episode:

The Chinese language is old - really old - and so provides a level of continuity with the past that doesn’t quite exist anywhere else

Many of the idioms in use today are thousands of years old but have been repurposed - online shopping events are described using terminology from ancient wars

Yet the language and its script has been modernised in recent times for political reasons

We explore whether the lack of study about China in the West is down to the nature of the language

You can also listen to the podcast on Apple, Amazon, or Spotify.

As always please do share, comment, and subscribe. We’ll be back next week with more What China Wants.

Many thanks for listening.

***

Here is the transcript of the recording:

Sam Olsen: Hello, and welcome back to What China Wants with me, Sam Olsen, and Stewart Paterson. Today, we are doing something slightly different. Rather than looking at the geo-politics or the geo-economics of China, we're going back to something that we originally started doing with What China Wants a couple of years ago, looking more at the culture of China.

If you read my stuff before, then you'll know how obsessed I am with all things Chinese, whether it's music, or literature, or whatever. But all of that is based on the Chinese language. And admittedly, I never really got around to perfecting my Mandarin. Stewart, are you cognizant of Chinese?

Stewart Paterson: Not a word, Sam, I try and master English, and I'm not that good at that.

SO: So I think what will be useful if you wanted to look at the Chinese language would be to have someone who actually knew what they were talking about. And thankfully, today, we are joined by such a person in Andrew Methven. Welcome, Andrew.

Andrew Methven: Thanks Sam, thanks Stewart, it's great to be here. Thanks for having me.

SO: And you write a weekly newsletter, which I think probably started about the same time as our really called 'Slow Chinese', which is really good reading, if you want to know a bit more about the Chinese language. What is your connection with Chinese, and how did you get involved in it?

AM: I guess like many people that ended up taking a China-based career, it was not a particularly orthodox way to go. I first went there in 2002 travelling, so I took the train from the UK and eventually made my way to China, and then stayed there, initially for around a year backpacked around the West of the country. And when I did that, I started to learn Chinese self-taught.

And then after that, after a year out of China, I decided I wanted to go back to Asia. So I then based myself in Taiwan, for overall around three years. When I was there, I decided that I wanted to learn Chinese and then focused on that. I then came back to the UK and then took a Master's in Linguistics and Translation, a few years after having gone to China in the first place. So kind of self taught in terms of the language, but then did a little bit of formal study at the end,

SP: Andrew, so one of the things that one can't help noticing, when you listen to Xi Jinping, or for that matter, most Chinese actually is that they are incredibly proud of the antiquity of their civilisation, and obviously, their language is a large part of that. Under the Communist Party, it almost seems to have become a sort of totem of national power, the continuity antiquity of Chinese civilisation and what it has given the world.

Can I just start by asking, how old is the Chinese language? And is the sort of ancient Chinese language recognisable as being the same language that is spoken today in China?

AM: So before I answer the question Stewart, I'll just qualify that there are not a genuine expert in terms of the evolution of the Chinese language as a linguist, but just from my own observation, and reading and learning about it. So if you read any speech by Xi Jinping or others, about Chinese civilisation, they'll normally say it's been around for 5000 years. So that then goes all the way back to I think, even deeper in history than the first dynasty of China, which was the Xia dynasty. So we're talking like 2000 BC type time, in terms of the language.

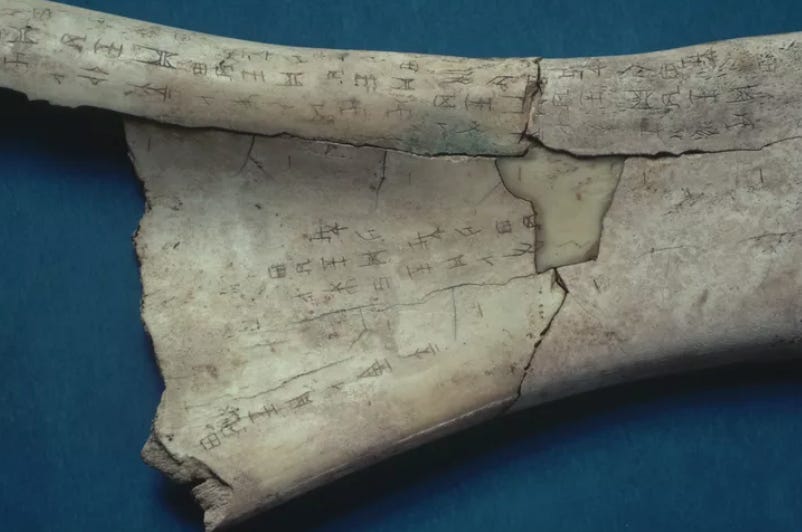

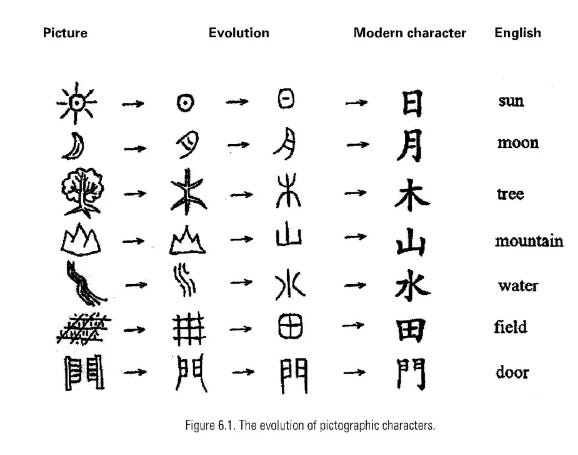

There's no written records of anything that deep in Chinese history, and the first proto-Chinese writing that there is, is called 'oracle bones' and in Chinese as jiǎgǔ wén. And so these are very early Chinese characters that are carved into bones, whether they're animal bones or tortoise shells.

And to your point about, are they recognisable? Well, actually, they kind of are, amazingly, so if you were to look up any Chinese character in the dictionary or online today, you're normally given a graphic representation of how that character has evolved over the years to what it is now. Often, you can see how it evolved from its early oracle bone design to what it is now. So a good example is characters like the one for mountain 'shān', or people 'rén'. These can all be traced back to the oracle bone, original characters, and we're talking around 1000 BC, so still very, very old, although not quite 5000 years.

SO: On that, Andrew, just to be clear, for the listeners, we're not talking about the whole of modern day China though, this is very localised, right? And it's something that originated in a certain place as well as a certain time?

AM: Yes, so again, my limited understanding is that going back that far into the depths of Chinese history, this was a relatively small region of what is now China, focused around the fertile plains of the Yellow River in the Yangtze River. But over the centuries, obviously, that has gradually expanded as the Chinese empire expanded and contracted over the centuries. So yes, I think the original part, in fact, the oracle bones themselves, have only been discovered in a very small geographical part of China. And so there's a lot of inference that goes into the understanding of them as well, as far as I know.

SP: So if we fast forward the Communist Party, I believe I'm right in saying introduced a sort of simplified version of Mandarin. What was the sort of rationale behind that? And how does it differ from traditional Chinese?

AM: So I think first of all, it's probably helpful to just cover a few definitions. So Mandarin is the word that in the West, that is the English term for the common language that's spoken in China now, which in Chinese is called Pǔtōnghuà. So like the kind of standard language or the common language that everyone speaks, so that's Mandarin, and that's spoken. Whereas the characters, obviously, are the written form. There's only one form of written language, so wherever you are in China, no matter what dialect, or language you speak, you can still read the characters.

And so your question there, Stewart is about how the characters have been simplified, but the language itself, how it's spoken. Obviously, it evolves. But it's still pretty much as it was, whereas the characters, since the founding of the People's Republic, the Communist Party gradually started to want to simplify the characters as a way to improve and increase literacy across the country. However, the simplification of the characters had been starting way before that. And if you think of it almost as a shorthand, if you're a market seller of vegetables, or something in a late Qing Dynasty market, you're probably not going to use the really complex character to write on your vegetables.

So I think way before the CCP, came into power in China, there was already examples of simplification of the written characters, and also how, for example, the Romanization of the way that we all learn Chinese now through pīnyīn, brought in during the 1950s. But there were earlier versions of how the language was learned as well, which came in at the start of the 20th century, obviously, that predated the CCP.

SO: Well, actually it's funny you say that because I remember from my sort of history that in the early 1900s, at the same time as the Chinese revolution, there was also an aspiring revolution in writing, because weren't some people saying in China, they actually wanted to replace the Chinese script, totally and replace it with Western script to make it easier?

AM: Yes, again, I think that's an idea that the Communist Party played with or explored during that process of wanting to simplify the characters and also come up with a system which is now the pīnyīn system. But I think for most of Chinese history, as I understand it, Mandarin Chinese or Pǔtōnghuà was not the national language or the language that was spoken mostly across the country.

Actually, that's only really been the case since the early 1900s. And there was a very famous linguist who I'm just starting to learn about now called Wang Li, who was alive during the latter part of the Qing Dynasty. And it was actually people like that, that started to drive the move towards standardising the language, and it just so happened that Mandarin won, but it could have been another language, it could have been a southern dialect. And actually, during earlier dynasties, non-Mandarin dialects were the language that was spoken by most people.

SP: Andrew, I mean, what I'd like to ask is, in terms of oral communication, what's the degree of understandability, as it were, between the various dialects across China? So if someone only spoke their local dialect, so Cantonese, for example, and they were trying to speak to someone in the north in their dialect, is that possible without resorting to Mandarin?

AM: My experience of the dialects, again, this is just my anecdotal view, is that in certain parts of China where a non-Mandarin dialect is prevalent, so for example, in Yunnan or Sichuan, you can kind of understand most of what they're saying, even though it's a different language. It just sounds like a very heavily accented, but quite similar language. Whereas Cantonese, for example, or Shanghainese or Minanhua, which they speak in the east, you can't understand those, it's like the difference between French and English. And so it varies across the country, but generally, they're pretty distinct languages, although you with some of them, there's a broader overlap, so you can kind of get the gist.

SO: And in terms of the Pǔtōnghuà and the simplified characters, where does Taiwan fit in with this? Because, am I right in thinking that Taiwan is still use older, more complicated characters?

AM: Yes, that's correct. So just going back to the standardisation of the language. Mandarin Chinese, as I understand it, began to become more widely spoken at the turn of the 20th century. So before the Nationalists had come into power, and before the People's Republic was founded. There was already a move at that time to standardise the language to what is now Mandarin. But as I understand it, under the Nationalist government, that didn't go too well, and in fact, it was seen as almost blasphemous that you would try to want to do something such as simplify the characters or standardise the language.

And at that time, the standard language was called Guóyǔ. And that's still what they call the standard Mandarin in Taiwan. So in Taiwan, you learn Guóyǔ, which is standard Chinese, whereas in mainland is called Pǔtōnghuà. And Pǔtōnghuà was the name given to the language by the Communists after they came into power. But it was already a process happening in terms of the spoken language. In the written language, the characters in Taiwan are the characters that you would have learned three 400 years ago. So they're still the traditional or in Chinese, the complex characters. And likewise, in Hong Kong, Macau, probably in Singapore as well, places like that, you would see the traditional characters written, and you learn the traditional characters. So in those small pockets, they still write and use the complex characters.

SP: And presumably does that apply to things like calligraphy and art generally, that the traditional older characters are used?

AM: Yes, again, I'm not really a calligraphy expert, but my observation is that actually, they're kind of interchangeable. So in a really fluid piece of calligraphy, you might actually get something that looks even not like the simplified character is something that's even more simple, an abstract than the simplified character. Whereas on other examples, you would have something that's very clearly wanting to look like the complex version of the character, so I think there's far more artistic licence for interpretation.

SO: There's a far closer relationship between people's sentimentality, and writing in Chinese than there is between people in the West and the Roman script, right? Because obviously, calligraphy is such an art form, that people specialise in it, but you don't really get that in the UK, or America or France, or whatever. So how important is the actual shape of the characters and the writing for the soul of the Chinese people?

AM: Well, I think just the written form of the language is a really crucial part of obviously learning the language, but also gaining a deeper understanding into China and Chinese culture and history and how people think. And that's because - unlike in western languages, you can take English, for example, to access information about, let's say, you know, the Roman Empire, or the Greek Empire, or even during the Anglo Saxon part of English history, that's all in a different language. And so therefore, you have to understand that language to access that level of understanding and context. Whereas in Chinese, the characters that you're reading now, and the expressions that you read, and then use now in spoken language, some of them are thousands of years old, they still basically mean the same thing.

SO: Yes we've spoken about this before, and you told me some of the amazing old idioms still used today, we were racking our brains and trying to work out the oldest English idioms. And the one I mentioned to you was about being buried 'six feet under'. That's one of the few Anglo-Saxon idioms that is still around today. But you're saying many exist today, which are way older than the Anglo-Saxon period, and in Chinese history.

AM: I think pretty much any idiom that you would use in spoken contemporary Chinese language today, will have a history lineage, of anything from several 100 years to 2,000 or 3,000 years. So for example, Confucius ('Kǒng Fūzǐ') who was alive during the Zhou dynasty. We’re talking, 2,000 plus years ago, so many of the things that he talked about, and was written about by his students is still in use today in sayings that you would read in a newspaper article, or you would use in a business meeting today in China. So it's a lot more relevant. There's a much greater connection through the language between China and Chinese people now and the deep past.

SP: Andrew you came across one the other day when Xi was talking to the BRICS summit. For the listeners who aren't aware, BRICS is the sort of loose grouping of countries initially it was Brazil, Russia, India, and China, South Africa as a sort of potential geopolitical grouping of what we might call the global south.

AM: Yes, often in speeches by Xi Jinping, either at the start of it or the end of it, he will then use a Chinese expression which is normally like a colloquial phrase, or an idiom or something or a poem. So for example, during his speech at the BRICS conference, second or third line, he said, "liè huǒ yàn zhēn jīn, jiān nán mó yì zhì." The direct translation is 'fire is the test of gold'. So you can only find true gold if you heat it really hot, and then you can decide whether it's pure or not.

And that actually means something along the lines of 'you know who your friends are during times of adversity', which is fine, but it was interesting, the bit that probably didn't come across in the speech, which all the Chinese audience would have got, but probably none of the non-Chinese audience would understand, which is the word for BRICS, as in the BRICS countries, in Chinese is 'jīn zhuān guójiā'. So golden BRIC countries, and therefore, that phrase was selected, because the point is that BRICS countries are true friends during these times of adversity, but obviously, it wasn't translated in that way, and therefore, it probably wasn't understood.

Those kinds of things come up a lot where there is a deep cultural reference. Obviously, in this case, it's linked to a modern evolution of the language, 'jīn zhuān guójiā', golden BRIC countries, but often it's you need the cultural context and the background and an understanding of where that phrase or expression has come from to really understand it.

SO: Didn't you also mention about some of the idioms around 618, which I found absolutely fascinating. So just be clear, 618 is this shopping phenomenon that happens every year. And it really brought home to me when you're describing some of the things being said around it, just how old the language is, when we've got such a modern phenomenon being described in ways that would have been around 2,000 or 3,000 years.

AM: This is just one of many examples that I've come across over the last nearly two years of writing this weekly blog that I do. Take a really modern contemporary scenario, like livestream e-commerce in China. So something that is so representative of modern China now, but would not necessarily work outside of China. So livestream ecommerce. I just looked at how this was being discussed by people that were in the livestream rooms buying stuff and how the media was talking about it. Often, it's the case that when you look at the language that's used in these scenarios, there's links back to the past.

In this particular case of the Shopping Festival, which happens in the first half of June every year, it's the second largest of China's two main online shopping festivals. The two themes that came out of the language were actually nothing to do with shopping. So they were warfare, and agriculture. This is interesting to me, because actually, it just shows that first of all the connection with the past that's so important and relevant in the Chinese language, which you don't necessarily get in English, let's say. But then also, that actually, for the majority of its history, China has been an agricultural society, and at various stages, through its long history, there have been times of war and instability and conflict. The idioms and these colloquial phrases are the remnants of this history and this way of life, and they've travelled through time, literally and they're still used today. And they can still mean something quite similar, but in just a really different and very contemporary Chinese ways.

So taking, for example, the word for bargain hunter in Chinese or like trying to get a good bargain is 'hāo yángmáo', which means 'to pluck sheep's wool', or 'to pluck lamb's wool', and for some reason, I don't know why, that means 'to grab a good bargain'. And then there's a whole load of other words around that which mean bargain hunter, you know, bargain hunting blogger, and they all use the word for sheep's wool.

There are other phrases around that where for example, the phrase in Chinese for you get what you pay for, is 'yáng máo chū zài yáng shēn shàng' which means 'sheep's wool is on a sheep's back'. In other words, even if you think you're getting a good deal, you're only getting what you paid for in the first place. So I just thought that was interesting that throughout the overall language around shopping, there's this really strong theme of agriculture. And it's the same in other parts of society too. So for example, in the working world, the word for working people, obviously, there's a number of different phrases that you would use, the most obvious one is 'dǎgōng rén', so 'the working person'. There's also a colloquial word, which is 'shèchù rén'. The direct translation is 'livestock'. But it's come to mean 'the working masses'.

Going back to the shopping thing. Warfare was another big one. So if you're a bargain hunter, and you've been fighting for the bargain that you want to in the livestream room, and you didn't get it, one of the expressions that I read that was used quite a lot was this word called 'bài běi'. And this one was new to me. So 'failure North' is the direct translation. And then I read into it, and in ancient Chinese, the word for North, 'běi' also meant retreat, as in retreat from a battlefield. So this phrase, which is used in terms of retreating from a in a really aggressive bargain hunter kind of bunfight to get the best whatever handbag at the best price actually, the phrase that was used to describe that feeling was something that dates back to the Han Dynasty 1800 years ago, describing the retreat of a Chinese general and his army in defeat from a battlefield.

I just think to me, the imagery is so potent, and interesting. What's also interesting is that everyone in China that learns Chinese knows all those stories. You learn the Chinese characters, they're learned through writing them and repeating them, you learn idioms, and you learn them through stories. So every idiom has a backstory, therefore, the depth of understanding of not only the language, but the historical context and the cultural meaning and all these different stories everyone knows them. So if you say something, everyone understands where that's come from, and from a language learner point of view, on one hand, it's a huge challenge. Because obviously, as a foreigner learning Chinese, you don't have any of that background so you have to go through that pain. But then at the same time, it's also really motivating because the more you learn the background to the language, the more you gain in terms of understanding Chinese culture and history and the way that people think.

SO: I must say, when I started to learn Chinese in my late teens, that was one of the things that I enjoyed, because it's like learning Latin as a schoolboy, having to learn about Julius Caesar and his campaigns. And then when you start learning Chinese, you're reading about all the old stories. I found absolutely fascinating. It's incredible, actually, that more people don't learn about Chinese history in the West, because there's so much of it. You can never get bored of learning about all the battles and the court intrigue and the eunuchs and everyone. It's a story that keeps on giving.

But why do you think that we don't learn more about Chinese history? Is it because of the language? Do you think actually the whole thing is impenetrable to the west? Because of the different script? Because it's so different in terms of linguistic differences? Is that a real barrier to us learning about China?

AM: Well, I think on one hand, probably now is the best time ever in history to learn any language, because you've got technology as a tool to help do that. So on one hand, if anything, now is the easiest time ever to learn any language, including Chinese. But I think the challenge is, it's just so distant geographically, and also culturally as well, that it's quite hard.

I mean, you could say, for example, in the context of the UK, you could say, well, the education system hasn't really got it right, in terms of allowing for people to learn about the Chinese language at a young age. But then my question would be, "well, it's quite a big ask as well, because why is that relevant?" My kids, for example, you know, they're 8, 11 and 12, I would love them to learn Chinese. But it's really hard even for me to teach them because it's a big effort to persuade someone to learn this language that's really hard to do, and has no relevance to anything right now, but in 10 or 20 years, time is going to be crucial for people to know, because in order to understand China, and where it's going, I think it's critical to understand the language.

But I think that just how distant it is, it is very inaccessible as a language to learn, I think, and therefore, my feeling is that it will continue to be quite niche. And therefore people like me, that are quite focused on learning the language will probably remain a small minority, I think, certainly for the next five to 10 years, which I think is a shame, because beyond relevance to where the world is going at the moment, it's actually just really interesting, you know, at times inspiring and a worthwhile experience to do. But I think there's not the motivation there, and the systems there. But also, I think the tools aren't there either. It's not taught in schools. And I go back to the point I just made, which is, but why should it be?

So I think there's a real contradiction. I think maybe more could be done at the university level. I didn't start learning Chinese until I was 23, I think, 24. Maybe that's the answer, but I think something needs to be done to make it more accessible to people. I'm British, so in countries like the UK, but anywhere really, that has a significant interaction with China, I think it's really important.

SO: Andrew, thanks very much indeed for joining us. At the age of 52, I think I've probably left it too late. But it’s been an absolutely fascinating discussion. And hopefully, we'll have you back on again shortly.

AM: Thanks for having me. It's really been a fun discussion.

SO: Yes, and if you do want to learn a bit more Chinese, then 'Slow Chinese' is the name of your newsletter, right?

AM: Yes, so if you just Google 'Slow Chinese', it should come up or you could Google 'Andrew Methven Slow Chinese'. It's published weekly, it's aimed at a more advanced level of learner but it's presented in a way hopefully that means even if you don't read any Chinese, you can still pick up a few interesting facts or surreal and pointless facts about the language and culture - anything from plucking sheep's wool to losing a battle 2,000 years ago.

SO: Thanks so much, and we'll be back next week with more What China Wants, goodbye.

Share this post