Hello and welcome to the Episode 8 of the What China Wants podcast.

We are delighted to be joined today by one of the world’s leading commentators on China’s economy, George Magnus. Formerly the Chief Economist at UBS, George is a noted authority on what makes China’s economy tick. His book “Red Flags: Why Xi’s China is in Jeopardy” set the cat amongst the pigeons for those who assumed that what Beijing was stating about their hurtling-along economy was - and would be for some time to come - the reality.

Our main points:

China’s economy has reached an inflection point – the so-called “end of extrapolation” – and now needs reform to kick on to the next stage of development

But the renewed assertion by the Communist Party of politics over economics is putting future economic growth at risk

If China’s economy does continue to splutter then it will have a major affect on the world, particularly commodity prices and those countries that have China as a main or major trading partner

You can also listen to the podcast on Apple, Amazon, or Spotify.

As always please do share, comment, and subscribe. We’ll be back next week.

Many thanks for listening.

***

Here is the transcript:

Sam Olsen: Hello, and welcome to the latest episode of What China Wants with Sam Olsen and Stewart Paterson. Today, we're going to be asking a question which is a follow up to one of our earlier podcasts asking whether China's economy is shrinking, which I think Stewart gave a resounding answer, 'Yes'. We’re going to be joined by the eminent economist George Magnus. George is an Associate at the China Centre at Oxford University. He's also an adviser to some asset management companies, but you might know him more from the commentary he regularly puts out with the Financial Times the BBC, and so on. George is also the author of the fantastic book, 'Red Flags: Why Xi's China is in Jeopardy'. We're delighted to have George here, so thank you very much for joining us, George, and welcome.

Even though it was written a few years ago, I suppose we'd be interested to know whether the central thesis that Xi Jinping's China is running into economic problems still holds true, or perhaps even more so in light of the recent issues around COVID, and the increasing geopolitical tension. Stewart?

Stewart Paterson: Well, George, thanks very much indeed, for joining us, and welcome. What I loved about the book, George, is that I think it challenges a fundamental premise of many people's perception of China, in fact, probably many of our policymakers' perceptions of China, and that is that China's further economic rise is a kind of inevitability. Your book argues that this assumption is somewhat questionable, and I would suggest perhaps that recent evidence is rather supportive of your thesis. So, for the benefit of our listeners, perhaps you could just recap some of the main arguments as to why China's economy under Xi is perhaps more vulnerable than many people think.

George Magnus: Sure, and thank you, Stewart and Sam, for having me on your podcast. I think, after an eternity - it seemed like - working for UBS with a particular eye on Asian and other emerging markets during the 1990s and the 2000s, and then, having experienced our own financial crisis in 2008-2009, I think what struck me about China really was the sort of spreadsheet-y view, which is, "Gosh, look what's happened over the last 20 or 30 years. And if we just kind of project on a spreadsheet, so-to-speak, China's dynamism and growth going forward over the next 10, 20, and 30 years, this is what's going to happen." It struck me that for various reasons, having kind of sort of looked at the entrails of the Chinese political economy for some time, and travelled there a lot, that China, round about the time that Xi Jinping came to power, had reached something that I called in the book, 'the end of extrapolation'; in other words, throw your spreadsheets away really, because it's a different ballgame.

The economy is now replete with imbalances, which actually the outgoing Premier Wen Jiabao had already spoken about on two occasions in 2007 and 2011. A new leadership had taken over, who was enamoured with a much more kind of Leninist approach to political thinking and to policy, and I was bothered really, that the pragmatism and openness which really ran through the veins of China's policymakers and its economy, since Deng Xiaoping, were in danger of reversing or being corrected, though in fact, what was really what I thought was beginning to take place that it was going to become a more ideological place, that the state and the party were going to be given more emphasis, and that the sort of politicisation of business in China was going to become eventually a bit more of a problem.

We can get into some of these things. But the red flags themselves were really about issues where I didn't think that China's policymakers had oven-ready solutions and maybe had political difficulties and issues in actually reaching solutions. One of those was the consequences of excessive growth in debt, which really began with the measures that were taken at the time of the financial crisis in 2008-2009. One has to do with its currency management policies. The third had to do with rapid ageing; China's the fastest ageing country on the planet, not the oldest but the fastest ageing. Fourth had to do with whether China would actually get difficulties or find difficulties getting out of the middle-income trap or staying out of the middle-income trap because of difficulties and a stall in its underlying growth of productivity. On top of that China looked like – at least then, when I wrote the book - that it was facing the harshest economic, external environment that it had done since the era of Mao Zedong. So that really brings us kind of up to date. Those were the red flags, and that's why I thought China was more vulnerable than the cheerleaders with the spreadsheets were having us belief.

SP: Yes, and you mentioned the fact that you wrote the book in 2018. Time marches on, and a lot of water has passed under the bridge since 2018. But there's probably a lot more evidence now that's corroborative of your thesis than there is that contradicts it. What would you point to that might cast doubt on it that has happened since publication? And what would you point to most compellingly, that is supportive?

GM: Well, if I'm honest, then I'm going to find it easier to answer the question about what supports the thesis rather than what contradicts it. I suppose I do look over my shoulder quite a lot to see, figuratively speaking, just to listen to and see what other people are saying, and just to check that I'm not drowning in my own kind of rhetoric, so-to-speak. And so there have been moments since 2018, for example, China's management of the pandemic, certainly in 2020, where it's like somebody's giving you a kind of a kick in the ribs. You question your premises, you question your assumptions, you question the way that you think about things. You wonder whether, in fact, you know, China's actually got something that other countries don't have in terms of being able to manage through crises. The two major crises that I wasn't able to predict with any accuracy, of course, were the pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

But these have accelerated China's desire to prioritise and to champion self-reliance. They've identified a dozen different technologies, advanced technologies, where they want to be number one in the world, where they want their own producers, their 'national champions', to have 70% market share or more. And at a time, when we are all kind of scratching our heads about what kind of political economy do we actually think works in the kind of economic and political environment that we've been left to deal with in the 2020s, and where the state does play a bigger role, you wonder whether maybe China is actually more ideally suited to that kind of situation. So the role of the government, the role of the state in the economy is something which I do think about a lot and try to keep checking whether I'm going off-piste, or whether I'm still on track.

But against all of that, I would say that, that there's nothing in this sort of observable metrics that has really distracted or detracted me from my core. The demographics are playing out as one would have expected, the productivity is as poor as it has been, the issues that I raised about the renminbi, certainly as far as becoming a global currency is concerned, I don't really see any major breakthroughs there. The debt problems are becoming more acute, as we know, from the last couple of years, particularly with property companies and property developers.

And so I think all of that is kind of playing out pretty much as I thought it might. The government's attitude towards private firms and the recalibration of industrial policy in favour of state enterprises and the role of the party in the economy are definitely things that I was worried about, and there have been many, many more data points that corroborate that view. Plus, of course, the consequences of the pandemic and the war in Ukraine in terms of self-reliance, and China cutting itself off from the world, I think this kind of disengagement phenomenon, which is partly made in China and partly being manufactured, of course, in Washington, Brussels, London, and so on, this is something new, right? China prospered and the rising China was based on its engagement with the rest of the world. Disengagement will have consequences.

SP: Yes, that's a really interesting point, George, because this self- reliance, which seems to be a major plank of dual circulation policy, both sides in this if you want to draw this dichotomy between the West and China - and we can loosely define the West, it can be defined however you want - but both sides seem to be very alert increasingly alert to their trade dependencies and their level of reliance on each other. China seems to have a much more coherent plan, or seems to be expediting a better plan or taking greater action than the liberal democracies do in terms of trying to immunise themselves from the fallout from economic statecraft, the potential to use economic statecraft to try and inflict harm on one another.

In a way, it seems odd, doesn't it? Given how much China has benefited from the global trading order and investment order as it stands at the moment, to be walking away from it? How do you explain that? Is it fear of Western sanctions? Or does it represent a sort of ideological shift towards sort of self-resilience and part of national aggrandisement? It's sort of a real mercantilist turn that you simply shouldn't be dependent on foreigners for technology or frankly, anything else?

GM: Yes, that's a great question. I think that there is no question that really the sanctions regime implemented against Russia, and which the Chinese are quite anxious about. As far as we know, because there may be a lot of things going on, that we don't know, or that I don't know, and certainly things going on under the radar screen. But major Chinese companies, for example, have not really wanted to put themselves at risk of incurring secondary sanctions by engaging in big commercial transactions with Russian companies. Chinese banks have really stepped away, as far as we can tell, from financing big energy deals with Russian companies. So as I said, no question that China has been, I think, thrown a curveball as it were, by the implementation of sanctions, coordinated by the West, I mean, the politically defined West rather than geographically defined. And there's a sort of 'no way, José' theme that kind of runs through China's policies here, which is, "we're not going to get caught out by this".

And now it's a moot point as to whether China can insulate itself successfully, in every sector, in electronics, in semiconductors, in finance, for example. I don't have any qualms really about some areas of technology, and of course, electric vehicles, although, you know, most of the kinds of producers are foreign, but in battery manufacturing, in artificial intelligence and surveillance equipment in quantum computing, in lots of different areas, solar panels and green energy, China is in a very good position. But there are a lot of areas where it's not in such a good position, and it still has very, very high dependency on the dollar system on advanced semiconductors and other sophisticated forms of technology.

So why are they doing this? Or why are they exposing themselves to being cut off or having frostier relations with suppliers? You can understand why Americans want to diversify their supply chains, but of course, the Chinese want to de Americanise theirs too or de-Westernise, theirs to some degree. And I think that it's just the question of politics trumping economics, as it often does, particularly at times of stress. And we shouldn't forget, of course, that historically, China has had these waves that go over centuries rather than years. But these waves in which it's opened up to the world, and then closed up, opened up to the world and then closed up.

The perverse thing about this is that as we know, from China in the 1980s, 90s, and 2000s, it was very willing to learn and engage with the rest of the world, and there were massive increases in you know, cultural exchanges, student exchanges, scientists' exchanges, and so on, so forth, amongst other things. And now this has all got a slightly frostier feel about it as China kind of feels like they don't need the West any more, 'we can do things on our own, we don't really need you', or that's what they like to themselves. In some areas it might be true, in other areas it might not be true.

SO: Just on that, Deng Xiaoping was well known for saying that we must learn from the West and interestingly with the history you can go back into the great revivalist movements in the late 19th century and early 20th century and the newly republican era where people did actually look to the West for inspiration and for science and culture etc. And we have had one of those 'golden periods' now, where I suppose the politics took a backseat.

What is interesting is that there still seems to be people in the West who disagree - in fact I was on a call with some very senior individuals earlier today, who insist that in China, economics is still in the driving seat rather than politics because economics is so important to the welfare of the nation. What would you say to people who think that economics is still in the driving seat? Do you think they actually it is fair to say that politics really does trump everything now or do you think that it is more nuanced than that?

GM: Well, I was just thinking about what I would respond to that. I think I would say that from, from my perspective, I don't think they understand Leninists. And I think that there is no question about the Leninist hue of Xi Jinping and his thoughts of 'socialism for a new era', Xi Jinping Thought and so on and so forth, embedded now in the Constitution, not just of the Party, but of the country as well, and which people are being taught at school, often from very young ages, etc.

So this is a political ideological foot forward, and they believe that, obviously, that if they follow the policies of Xi Jinping and Xi Jinping Thought that the economy will deliver the reduction in poverty, which they claim already has been achieved by their definition, plus the construction of a prosperous nation, and indeed, a dominant nation by the middle of the century. They haven't talked very much this year about common prosperity, which was aired and spoken about a lot in 2021. It made a fleeting reference in one or two of the documents presented at the National People's Congress in March of this year, but I think that's been sort of side-tracked in a way because of the economic crisis at home.

I suspect that China will find its way through with, I imagine, Xi Jinping at the helm, still into 2023-2024, and I think that we will hear more about common prosperity policies. But, you know, we can be critical about common prosperity and whether it has any substance or whether it's just a campaign. But actually, the belief in Beijing is that if you get the politics right, the economics will follow. I don't honestly believe that they think about it the other way around. They want prosperity for people, of course, and they know that their greatness and the projection of power in the world depends on their economic heft. But they just have a different kind of perception about how to create that compared with me.

SP: So George, I think that's very interesting, because one of the themes that we've been talking about is the downplaying of economic growth as a source of party legitimacy. One of the reasons for that we think, is precisely what you point out in your book, that the economic model is showing many signs of being broken, it needs an overhaul, and it needs an overhaul by economists, not by politicians. You use in your book the adjective 'brittle', to describe Xi's machine, which many observers would say is, the antithesis of what has gone before, which was pragmatic and flexible, and technocratic excellence was rewarded. Whereas under Xi, it seems more as though being true to the ideology and loyal to the man seems to be more of a prerequisite for promotion than technical excellence, and the past execution of good policy.

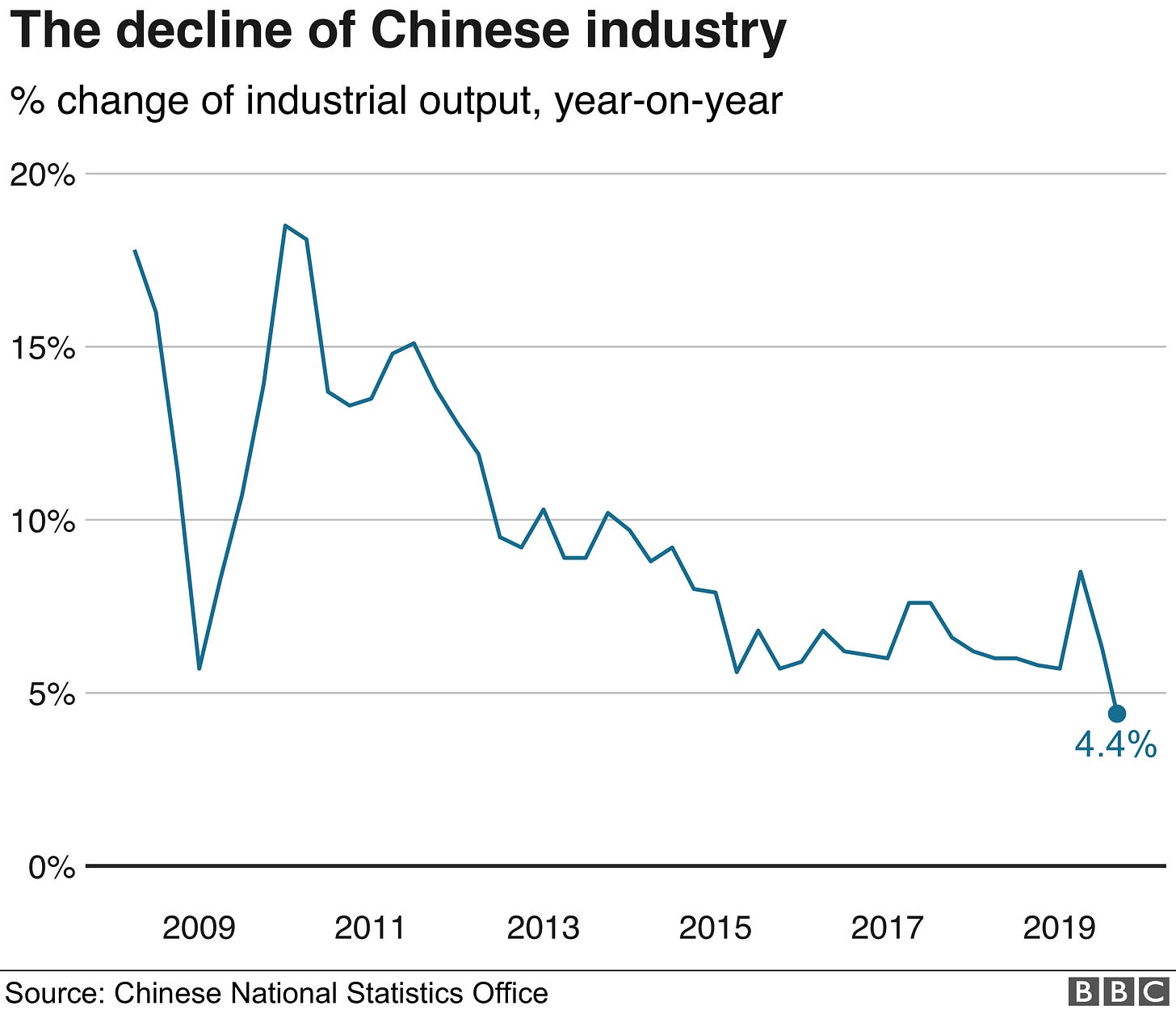

So if that's the sort of direction we're going, does this make you worry about the size of the economic fallout that we might see from China? Because if we look at the global economies since 2009, say the financial crisis, China's accounted for about 40% of the world's growth. And we're all well aware of the fact that macro-economic data out of China has become increasingly politicised and is really just a source of, of national propaganda now in many ways. But how big could the fallout in from China be? And what could be the global ramifications of that, if Xi carries on down the brittle road is at were?

GM: Right. So, just to contextualise the answer and relate it to the previous answer to Sam's question, and also to anchor it in what I said right at the very beginning when I was talking about 'the end of the extrapolation', what I what I mean by that is that China's development model needs a makeover. Because the old one doesn't really work anymore. And we know that doesn't work because property market has been keeling over. You can't keep on investing ever bigger shares of GDP without getting capital misallocation and diminishing returns and growing debt problems.

So we know things have to change. I haven't been there since 2019, probably very, very few people have, and so it's very difficult to keep tabs on this. But my impression certainly is that China's leaders, many of them know that some things have to change, I just don't think they can bring themselves round to doing the kind of changes that I think are necessary. And many of these revolve around the construction of institutions. Institutions play an absolutely critical role in economic development, whether you're poor, whether you're a middle income country, and even for Britain and the United States and Western Europe.

The robustness and inclusive nature of institutions are really what drive economic progress, I would say, because that's how you basically get more bang for your buck in terms of productivity. So the implications of all of this if China cannot change, or it finds it politically difficult to change, which I think is the case, I think the outlook for China over the next 10, 15 years or so, is that it's a low growth economy. It's going to be two and a half, three, three and a half percent per annum, on average. The question is how much disruption accompanies that sort of growth rate? Is it a lot of disruption, or is it minimal disruption? And are the political constructs in China robust enough to be able to manage with minimum disruption?

But a slower-growing Chinese economy has huge implications for the rest of us. We fret every day now about oil and gas and commodity prices and resource prices and rare earth prices and goodness knows what else. But a China that grows at a much slower rate, once the shock impact of the Russian invasion is over, China's impact on global commodity prices will be to depress them basically, if the property market, is as languid or languishing for the next years, as I expect it might.

Supply chains are going to exert a very significant impact on people's perceptions about inflation. On the one hand if supply chains are recalibrated and new opportunities, and new investment outlets are found in say Malaysia or Cambodia, Vietnam, India, and so on, if there are new business opportunities, there are new downward pressures on prices as a consequence of that. On the other hand, of course, disruption to supply chains and the possibility of Yuan depreciation in the future, will have an opposite effect on inflation. So, I don't think it's easy to say categorically a low-growing China will be positive or negative for inflation. Rather, it depends on the context in which this happens. But yes, I mean, for 75 or so countries that have China as its biggest trading partner either in exports or imports or both, then a slower growing market, or a slower growing GDP should we say, will have consequences, and it means it's not obviously great for global growth, or you have to find different markets that are growing more quickly.

SO: So George, just to finish off, you've given a very eloquent description of how that are indeed some red flags in the Chinese economy. And if I could just summarise, it seems that the end of extrapolation is basically the cause, and because the Chinese economic model needs a different direction, because it got to a certain level of development. But the problem is, is that the politics have really interjected to make sure that those changes in the economy that need to happen to continue with good growth haven't really happened and can't really happen because of the political system they rest upon.

So here's the final question for you. If that is the case, then surely there must be some kind of blowback onto the politics from the economics, if the economics is stuttering because of the politics. But is that blowback strong enough, in your opinion, to put at risk, the regime of Xi Jinping? He's obviously got his party congress this autumn, looking for re-election? And do you think that the economics are bad enough yet, or might be soon, to challenge Xi Jinping on his home turf?

GM: Well, okay, let me be a hostage to Fortune. As people probably know, there's certainly been speculation this year about opposition to Xi Jinping, who has not been able to bask necessarily in the kind of environment he would have wanted, in this run up to the big 20th party congress, whenever it's going to be held later this year. And the pandemic, and particularly the Omicron experience in Shanghai and Beijing and other places obviously played a part in that. And additionally the way that China's support for Russia has also been lots of rhetoric in favour, but it's obviously not really worked out the way they planned. I think that speculation is just, that's all it is, it's speculation. I don't think we have any real basis for believing that there is an orchestrated or planned move to oust him or to elbow him aside.

However, lots of positions have to be filled on the Politburo Standing Committee, and also at various levels in the party hierarchy, and we'll see whether he gets his way with all his nominees or whether there is opposition from the party. These things will become clearer to Sinologists in the fullness of time, but I think the working assumption is that he will still be nominated to have his third term at the party congress. I would say with the economy, the significance of the economy, I think, is changing. So rapid economic growth and high levels of employment always used to be, I think, deemed to be the core of the Communist Party's legitimacy to rule and the leader’s authority within the party. They're still important, not so much GDP growth itself, but actually jobs are really important and jobs are certainly at a bit of a premium right now. But that's a kind of a “watch this space”.

I would add to that, that a rising China is the basis for the way in which Xi Jinping has claimed and staked legitimacy of the Communist Party in China and his role within it, if a rising China is basically back in the melting pot, because it can't grow that quickly or because things don’t work out in the way that they have done in decades gone by, and the rest of the world starts to look at China in a different light from an economic point of view, these things then can become quite important to the position of the General Secretary himself and for those that would be his enemies, that might now be quite frightened to put their heads above the parapet but might not be so frightened in years to come.

SO: George Magnus, thank you very much. That was a fantastic tour de force, not particularly encouraging for those wanting to invest in China I should think.

SP: George, thank you very much for joining us.

GM: And thank you for having me.

China's Economic Red Flags