Happy New Year to all.

2020 was a seminal year for China. Beijing took advantage of the chronic disruption caused by the Covid virus to accelerate many of the changes it already had its eye on, as well as taking advantage of new opportunities when it could. The result for China has been a more aggressive foreign policy, a reorganised economic strategy, a heavy push into technological development, and a stronger military.

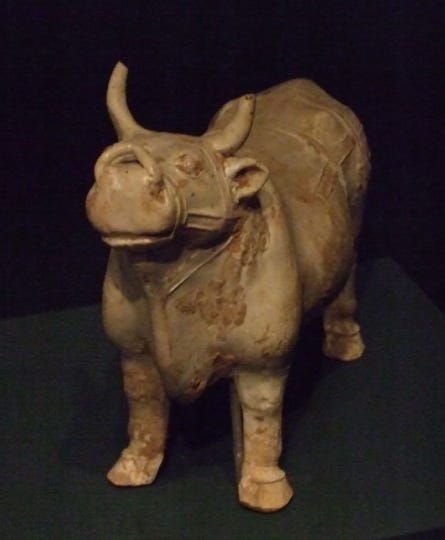

The question I’m going to answer in today’s newsletter is what we can expect from China in 2021, the Year of the Ox.

In the Chinese Zodiac, oxes are known to be strong-willed and persistent, and achieve their aims according to their own ideas, without being influenced by their environment. It sounds like the perfect match for what we expect China to do this coming year.

In writing today’s letter I’m pleased to say that I have been helped by my new colleague at MetisAsia, Alexander Neill. Alex is a long-standing China expert, formerly a government analyst and more recently a senior think tank specialist focusing on China.

No Longer Hiding or Biding

The most striking change we saw from China in 2020 was its about-turn in foreign policy.

Its longstanding “hide and bide” strategy, where the country quietly builds up its power without being seen to challenge the US-led Western hegemony, was laid to rest. What has emerged is a metamorphosed China, brash and unashamedly eager for power, recognition, and influence.

Much of this newfound confidence comes from its apparent success in fighting the pandemic: the country has defeated the virus, and so it is unbeatable elsewhere. This is a theory that is going to be widely put to the test in 2021.

No Return to Calm

There is disappointment in store for those hoping for a return to “peaceful” US-Chinese relations now that President Trump is set to exit the stage. Not only has the overall dynamic changed in Washington (China doves are a rare species these days), but Beijing under President Xi has no intention of rowing back on the foreign policy changes it made this last year. In fact, Xi is almost certainly going to double down on them.

We will get a full sense of where China is headed from the country’s set-piece political events that are coming up.

The biggest fanfare will be in July when the Chinese Communist Party will celebrate the centenary of its founding. In 1921, a Moscow-sponsored Dutchman named Hank Sneevliet gathered together 57 activists (including one called Mao Zedong) in Shanghai to launch the First National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party. Twenty-eight years later the CCP was in charge of the whole of China.

Whilst we can expect a heavy global media push to shout about the CCP’s successes, the most important set-piece this year in terms of the bricks and mortar of where China is headed will be the National People’s Congress in March. Running for two weeks in Beijing, the NPC is China’s highest-profile annual political meeting, attended by President Xi and other top leaders. The forthcoming NPC’s proposed agenda for 2021 includes the normal reviews on government reports and budgets, but more interestingly will also discuss the next economic Five-Year Plan, the country’s fourteenth.

China ended 2020 the only major economy to have ended on a high, even if the figures may not have been all they seemed. Our own research suggests that even though China’s exports surged at the end of the year, much of the damage done earlier – factories decimated, labour laid off – has yet to be fully repaired.

The Five-Year Plan will take the new economic reality into consideration, and is likely to support the new Dual Circulation strategy, a defensive move that seeks to protect China from US interference in its export-led growth. Given the mood in Washington, China may need more than this to defend itself this year, economically.

Climate Change Disaccord

The Five-Year Plan is also expected to kick-off progress towards China’s recently announced 2060 zero-emissions target. Indeed, it will be interesting to see what greenery the Plan contains given that the United Nation’s Climate Change conference, COP 26, is coming up in November.

Climate change has long been touted as something for the US and Chinese to work together on, and in theory it makes sense. Both Xi and Biden have been vocal proponents of the need to change the narrative on the environmental agenda both at home and abroad, and it is an era-defining subject that by definition has to be solved internationally.

However, the environmental agenda may actually become another area of contention.

Both America and China have less than perfect records when it comes to environmental policy, which could and likely will act as targets for the hawks in both governments. For the US, it is its (temporary) abandonment of the Paris Agreement. With China, despite all its talk of supporting the climate fight, Beijing is still financing an astonishing 60 coal power plants along the Belt & Road. Add to this the general lack of trust that many, mainly Western nations now have in relation to the People’s Republic, what should be a topic of unity could end up yet another source of discord.

Internationalising Money and Technology

I wrote last week about the potential for an RMB bloc. Whilst we don’t think that there are many countries yet willing to abandon the US dollar in exchange for the RMB, in 2021 China will continue to push the internationalization of the RMB with countries that it thinks it can trust, either in “traditional” form, or as a digital currency.

Countries willing to further integrate with China’s currency are most likely to be found along the Belt & Road and the Digital Silk Road, in Asia, Latin America, and Africa. These nations are likely to take China’s lead with technology too. As I have written about here, China’s global tech dominance is growing and although we expect the West (including Japan) to push back on this in 2021, it is probable that Chinese tech will continue to make inroads, especially in the developing world where there is demand for cheap, Chinese connectivity products.

China and Europe

The EU has come under some scrutiny in recent months with its new Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) with China. Critics say that the EU has thrown human rights (the Uighurs, for example) under a bus, whereas its supporters say that the CAI will boost national economies and help the recovery from Covid devastation.

Notwithstanding the CAI, the EU is becoming more wary of China. There has been strong rhetoric from European politicians in recent months against perceived bullying by Beijing, and the EU-US Dialogue on China that was launched in October 2020 could well bring coordination to pushback on China’s ambitions.

China won’t meekly accept this, however, and we can expect Beijing to carefully pick off countries one by one with the promise of trade or other goodies. Greece is particularly exposed given its main port, Piraeus, is now in Chinese hands, but so is Germany.

Chancellor Merkel has continually refrained from being overly hostile to the People’s Republic. Partly this is because of her country’s economic requirements - China is the biggest market for Volkswagen and many other German champions.

Merkel and her allies are also still believers in “Wandel durch Handel”, which is the idea that closer trade ties will push China toward a freer and more open political system. I saw this theory first-hand whilst working in the US Senate in 2004, where a blind eye was wilfully taken to Chinese steel dumping with the hope that it would somehow encourage the growth of democracy in China. The theory is now broadly discredited amongst most Western commentators - and those in China too, who long ago realised that the CCP is never going to introduce democracy.

Whoever replaces Mrs Merkel this year will surely take a different line on China, bringing Germany into line with most of the other European countries. This includes the UK.

Prime Minister Johnson’s government has become more hawkish on Beijing in recent months, and London is at the vanguard of building a new cross-border coalition to better stand up to China, a coalition likely to include Australia, Japan, the US, and others.

This new international alignment will be tangibly represented when the UK Royal Navy’s flagship, the aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth, deploys to the Indo-Pacific later this year. Its escort is likely to come from Australia and the US, and there is talk that Japanese planes will land on the carrier. A vocally assertive China is not going to allow what it considers to be the latest attempt by the West to contain it to pass by without some kind of protest.

2021: A Year of Action

The year ahead is looking like an active one for China. It is also a potentially dangerous one. Whilst Beijing has welcomed the arrival of Joe Biden, it shouldn’t - and probably doesn’t - think that he will retreat from many of the steps that President Trump took to push back on China. What’s worse from a CCP point of view is that Biden is by nature collaborative. He is likely to bolster the international coalition that is coming together in response to what many consider to be China’s bullying, and this will make like tougher for Beijing.

There may even be the chance of some kind of flashpoint, such as in the South China Sea, if Beijing feels that its interests are being threatened too much. Even though most China watchers think some kind of conflict with America unlikely (see my article here), President Xi has made it clear that his country will not avoid conflict if pushed.

Of course, one of the best ways to avoid conflict is to better communicate. Unfortunately, one of the weaknesses of the zodiacal Ox is its poor communication skills, and in this China is ahead of the curve - 2020 was not a golden year for Beijing’s public relations.

Unless China’s leaders learn how to better communicate with the world then it is going to find this year much harder going than it should. And that will be a boon for those Western hawks that seek to keep China constrained.