Dear all

We’ve spent the last month or so looking at China’s approach to intellectual property, and this week we ask a specific but important question: is China happy to passively outcompete the developed world when it comes to innovation, or does it want to destroy the competition?

This is obviously an important point for developed world policy makers to consider. It’s one thing for their companies to fold thanks to market pressures; it’s totally another to see them sink beneath the waves as part of a deliberate policy set in Beijing, if indeed that is what is happening. As the example of Nortel shows, seeing commercial powerhouses destroyed by foreign rivals is never easy, especially if underhand measures were taken to achieve it.

I’ll be back this Saturday with more on China’s history. In the meantime, please remember to subscribe if you are enjoying reading this…

***

On 25th January this year, President Xi Jinping sent a recorded video to the World Economic Forum with a simple message: that the interplay between China and America should be more like fair competition than a fight to eliminate the other. “We must advocate fair competition, like competing with each other for excellence in a racing field, not beating each other in a wrestling arena,” Xi said.

These were strong words, aimed not just at the US, but at many around the world who are suspicious that China wants to supplant America and its Western allies as the global hegemon. Not only that, but his speech was designed to allay fears that, in apparently wanting to become hegemonic, it is trying to reduce the effectiveness of the Western political, military, and economic systems, and thus their capability to compete against the People’s Republic. There are reasons to think that this might indeed be the case.

In the economic sphere in particular, there are direct accusations that China is not only trying to outcompete the West, but to destroy its ability to create economic competition in the first place. According to Rob Atkinson, head of the technology think tank ITIF, “China’s trade policy is a way to accumulate power for themselves and to degrade that of their adversaries.”

In other words, Beijing has set out on a path of innovation mercantilism.

Mercantilism is an economic policy whereby governments used their economies to augment state power at the expense of other countries. Its traditional heyday was in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in Europe, when political and military rivalries between England, France, and Spain spilled over into economic conflict. As the great British economist Adam Smith described it, the doctrine of mercantilism taught that nations should beggar all their neighbours (that is, impoverish them) to maximize economic gains.

By about the middle of the nineteenth century mercantilism had been rejected by Britain and France. The British Empire embraced free trade, and used its power as the financial centre of the world to promote the same. By and large mercantilism has disappeared as a way of doing things – until, perhaps, now.

As Atkinson argues, China has embraced mercantilist policies in its economic development. This includes manipulating its currency to gain an unfair price advantage in foreign markets, providing hefty subsidies to its domestic companies, and obtaining significant amounts of foreign IP without paying for it.

The impact of this has been to give an unfair advantage to Chinese firms, and a consequential disadvantage to foreign companies and the countries whence they come. This is especially true in technology-based industries, which usually have high fixed costs for design and development, but relatively low marginal costs for production.

If China is heavily supporting the initial, capital intensive part of this development path, then it makes the unit cost of any resulting goods and products that much cheaper. In order to compete, foreign firms have to reduce their unit costs too – and the easiest way to do that is to reduce the expensive research and development (R&D) at the start of the process.

Once this downward spiral starts, it tends to take on a momentum of its own. Companies, particularly from the developed world, find themselves losing out to Chinese rivals, leaving them with less cash to invest in R&D. Their products decrease in quality compared to Chinese ones, and then this becomes another reason to lose against them. This is exactly the flat spin that Nortel found itself in against Huawei, as we discussed last week.

At a more macro level, China’s policies seem to act as brake on innovation. A study by the US National Bureau of Economic Research found a “robust, negative impact of rising Chinese competition on firm-level and technology class-level patent production”. This in turn, said the report, had a deleterious effect on global employment, sales, profitability, and R&D expenditure.

It isn’t just individual companies that can be undermined by this mercantilist approach; whole sectors have found themselves taken down by Chinese competition.

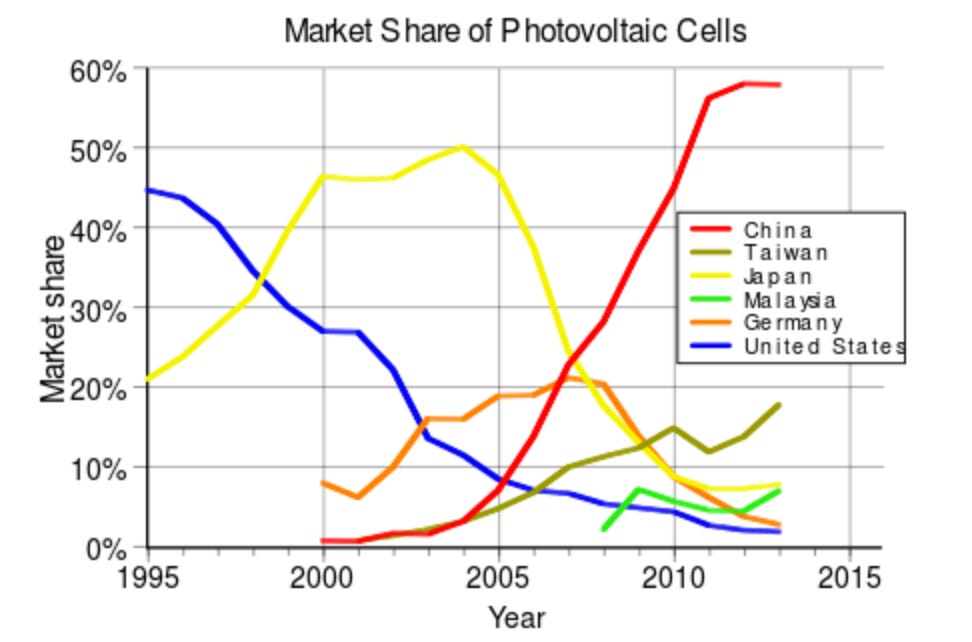

In the 1990s the Chinese photovoltaic (PV) sector was just a fraction of that in Germany, Japan, and America. Thanks to massive subsidies for both R&D and production, China's solar-electric panel firms drove down world prices by 80 percent between 2008 and 2013. The German and Japanese PV industries, unable to compete, are now almost dead, and the American one is in far from good health.

By contrast, China is now the largest producer of solar panels, exporting 38% of the world’s total in 2018. Leading Chinese PV manufacturers have built production facilities in nearly 20 countries worldwide, with products exported to nearly 200 countries and regions.

Looking at these examples it’s not hard to see why Atkinson might be right. And yet - there are objections to this theory.

Importantly, China is not yet self-sufficient in many industrial sectors. In the automotive sector for example, where the People’s Republic is now the world's largest auto market in terms of both production and sales, around 80% of the chips needed for car engines and gearboxes rely on imports. This is the same for many other sectors, and indeed China’s reliance on foreign tech has long been considered to be an Achilles’ heel.

To that end, there is a real fear in Beijing that America and its allies will remove its access to some of the tech that it needs. In fact, that process has already started. In May last year the Trump Administration moved to block global chip supplies to Huawei, and there have been proposals in Washington to cut trade with China’s largest semiconductor manufacturer, SMIC.

Given China’s extant reliance on foreign technology, it would seem self-defeating for Beijing to try and destroy the innovation from abroad that it needs for its own economy. Unless, of course, President Xi believes that the country is now strong enough and innovative to not have to worry about what happens in other countries. Dual Circulation – a strategy designed to cut its dependence on overseas markets and technology – would seem to indicate that whilst the country may not be quite ready for technological autarky, it has a plan to achieve this soon.

If China does have a policy of innovation mercantilism then there is plenty of pain coming for developed nation firms. Beijing is ramping up its plans to be the dominant power in global high-tech manufacturing, not least with its China 2025 policy (which is still very much in swing, despite what the Chinese leadership told Trump).

This does not necessarily mean the end of developed world innovation. The US still outspends China on R&D as a whole, and there are signs that some nations are waking up to the need to spend more on research. London, for example, has announced that it is increasing UK investment in R&D to 2.4% of GDP by 2027.

The best way for developed countries to compete against possible Chinese innovation mercantilism is to bring their concerns to light, and heavily push back against unfair practices. The risk of course, and one highlighted by the Global Innovation Index, is that protectionism will flower in the coming years and have a wider ranging negative impact on innovation. The alternative – that developed nation companies are gutted by Beijing – is not something that governments will be able to withstand for long.

It is worth remembering that no matter how bad the situation gets, there is always hope. The free trade that Adam Smith championed emerged out of the darkest days of beggar-thy-neighbour policies, and went on to be perhaps the single biggest driver of wealth creation in history. Get the relations with China right, and there’ll be life in free trade yet.