Chinese IP theft: “The greatest transfer of wealth in history”

How China's domestic innovation plan may face challenges ahead

Dear all - thanks again for reading, liking and sharing this news letter: the more people understand What China Wants, the better. Please subscribe if you haven’t already.

I was going to do a post today on the delight that China’s media (social and national) are taking in the US Capitol riots, and the state of Western democracy in general - but it’s just too depressing. Beijing is actively courting the world with its “China model”, and stupid, self-inflicted incidents like this diminish the US in the eyes of billions of people. Joe Biden has a lot of work to do to even partially repair America’s image, at least in Asia, where I am.

I’m going to write instead about something marginally less depressing, because there is more we can do about it. Namely, tackling China’s rampant theft of global intellectual property (IP), something I have worked on for years. You may have heard a few headlines, but as you will read below, the details are literally incredible.

***

Innovation is at the heart of China’s plan to become be a, if not the, global superpower by the 2049 centenary of the founding of the People’s Republic. In the most recent Five-Year Plan, the focus was on high-quality rather than high-speed growth, and the word “innovation” was mentioned fifteen times in the twenty-two paragraph communiqué.

However, whilst it is true that China has increasingly proven itself able to innovate in recent years, it’s also widely recognised that much of the country’s technology thus far was actually developed elsewhere.

Indeed, a major reason behind the Trump Administration’s declaration of trade-war in 2018 was the continued theft by China of American intellectual property (IP). This is not a trivial activity. A 2019 survey of North American Chief Financial Officers revealed that Chinese firms have stolen from one in five of them at some point during the past decade. According to some reports, Chinese IP theft costs the United States $225 billion to $600 billion a year, a figure that a former National Security Agency chief called “the greatest transfer of wealth in history”.

For years the problem of Chinese IP theft was not taken seriously. It was mainly considered a problem of counterfeiting, which, although a problem for the brands knocked off, wasn’t made a priority for the US government. Some of the counterfeit stories over the years have been rich in audacity, like the fake Apple Store in the south west city of Kunming that was so believable that it even fooled its own staff. A cursory look around Chinese clothes shops reveals sports brands like “Ike” or “Abcids” for “Nike” and “Adidas”; you can treat yourself to a bag of “Legs” crisps (rather than “Leys”), wear “Dolce & Banana” sunglasses, and even eat fake eggs.

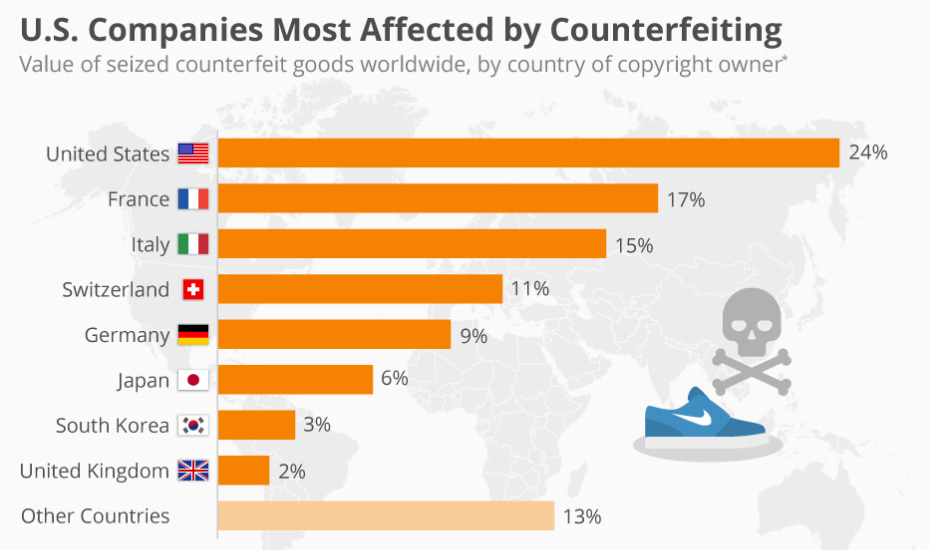

Counterfeiting is big business. According to a report headlined in the Harvard Business Review, Hong Kong and China are together said to be the source of approximately 86% of the world’s counterfeit goods, an amount that the US Chamber of Commerce estimates is worth about $397 billion. Fake merchandise accounted for 12.5% of China’s exports in 2016, according to the same report, and the country most impacted by these fakes was the US: nearly a quarter of all counterfeits recorded, most of which come from Greater China, impinge upon American-based IP.

Yet there is far more to IP theft than counterfeiting. China has also been accused of acquiring vast quantities of trade secrets from overseas companies, which it has then used to boost its own economy, often at the expense of international competition.

In the words of William Schneider Jr., former US Undersecretary of State for Security Assistance, Science and Technology, “China has institutionalized a system that combines legal and illegal means of technology acquisition from abroad.”

The legal part occurs with what is known as forced technology transfer. For years there has been a requirement for foreign firms to transfer their technology to Chinese counterparts as the price of doing business in the country.

Western carmakers like Volkswagen and BMW have handled this by only providing Chinese partners with near obsolete tech. Other sectors have been less wise. In 2005 the German company Siemens won a $788 million contract to provide high speed trains to China.

“This contract means that China will be supplied with the most up-to-date technology for high-speed trains,” said Siemens’s then-chief executive officer, Klaus Kleinfeld, at the signing ceremony.

Unfortunately, he was right.

In order to win the deal Siemens had to hand over its IP, which it did so willingly and with the full knowledge of industry analysts. Siemens’ technology transfer, added together with that of French train maker Alstom, which entered into a similar deal in 2004, has come back to haunt the two companies. The Chinese firm that received the European know-how, CRRC, has used this technology to become the largest train manufacturer in the world, and its most cost effective, thanks to enormous state subsidies. Siemens and Alstom have been forced to merge their rail units just to compete.

Sometimes Chinese companies are more proactive in their technology transfer schemes. When the same CRRC bought an obscure British semiconductor company called Dynex, based in the remote English city of Lincoln, it raised little concern. Now it appears that Dynex’s technology has been used to develop China’s latest railgun technology for use by the PLA Navy.

The US Navy has been working on railguns for over a decade, and for obvious reasons: using electromagnetism rather than gunpowder, they can fire projectiles at incredible speeds and at targets up to 100 km away, a gamechanger in naval warfare. That China appears to be in the lead with this battle-winning technology is thanks in part to British naivety in what the investment would be used for.

Astounding amounts of technology have been transferred by stealthier means - “a blueprint for technology theft on a scale the world has never seen before” as a US report put it. Most of the attempted and actual theft never reaches the newspapers; but as I saw for myself when I was the head of IP protection at a large American risk consultancy, for foreign firms operating in China it is almost a foregone conclusion that if there is a trade secret worth stealing, it will at some point be stolen.

One of the more blatant cases of IP theft that I worked on was for a prestigious European glass manufacturer that had set up a factory in an industrial park in one of China’s coastal provinces. Not long after the plant had come online the local head of engineering resigned, ostensibly for health reasons. Within months a new glass factory was being constructed within the same park. When the Managing Director of the European company went to inspect his new rival, he was shocked to discover that the plant was exactly the same as his own. As if that wasn’t enough, the Chinese company rubbed salt into the wounds by using photos taken from the European factory for their early marketing brochures.

The tale of a British high-tech firm explains why it is so hard for Westerners to stop this theft. The UK head office was called one day by one of its clients in Europe asking how and why they had been offered the exact same electronic sensor that the British company was famous for. The client had tested it and found that it met all the same standards; the only difference was the price, about half of the original. The results of the investigation were appalling, but not surprising.

Again, it was the local, Chinese head of engineering who was to blame. Citing the ill health of his mother he resigned, and was swiftly followed out the door by a number of other engineers. Unbeknownst to the British company, their former head of engineering had gone into business with his brother-in-law to manufacture the UK-designed products, using the technical specifications he downloaded before he went.

When the British company found out what had happened, they declared their intention to sue. However, there was a snag. The Chinese lawyer hired to fight the case found that the copycat company had raised investment from the local Provincial government. Having the authorities as a major shareholder meant, in effect, that no judge was ever going to rule against them, particularly on behalf of foreigners. There was nothing more for the British company to do except embark on a plan of mitigation and take the financial hit.

This is not to say that it is impossible for foreign complainants to win in China. In 2010 Microsoft won a case against a Chinese insurer for using counterfeit copies of its software, and in 2020 the famed American basketballer Michael Jordan won a trademark battle with a Chinese sports company.

In fact, as a result of the trade war China has made several commitments to the US to improve IP protection. These includeincreased IP protection enforcement, the elimination of forced technology transfers, and for the country to refrain from directly supporting outbound investments aimed at acquiring foreign technologies.

Time will tell if these measures are successful. What is clear is that they need to be if China wants to keep innovation at the heart of its economic plans, because no country can innovate to a world-class standard on its own. China will need international partnerships if it is to succeed with its technological development, and these are under threat if countries feel that they are still having their intellectual property looted.

There is though some concern that China won’t be able to get a complete grip of its IP theft problem. First, many of the problems with IP infringement are at the local level, over which Beijing has limited control.

Second, because often the IP theft is done for strategic reasons, and are actually helped by government agencies in pursuit of China’s overarching plan – as we will see next week.