Will China Replace Russia's Influence in Central Asia?

An interview with Dr Alexander Morrison of New College, Oxford

Dear all

Today we wrap up our series on China’s relationship with Russia with a fascinating interview with Dr Alexander Morrison, a Fellow at New College, Oxford, and one of the UK’s leading Russia experts. Alexander has a particular interest in Russia’s past and present involvement in Central Asia, a region which has become very much more aware of China’s influence in recent years.

We discuss below what Russia and China want from each other, whether the two bears can coexist in Central Asia, and whether the local population there wants anything to do with China in the first place. Hint: the tragedy of the Uighurs places a lead, but not the only role in this.

In the meantime please remember to comment and like and share and subscribe.

Many thanks for reading, and thank you to Alexander for his insights.

***

Sam Olsen: How does Russia see China, now and in the long-term?

Alexander Morrison: There has been a real coming together between Russia and China in recent years because of a series of shared interests. However, there is a lot of suspicion from Russia because of the unequalness of the relationship – China’s economy is much larger. Russia still has an edge in a few military areas, for example advanced fighter jets, but that’s it. This means that the relationship is likely to fall apart at some stage, perhaps at short notice.

The power relationship is unlikely to shift in Moscow’s favour because Russia is a declining power, although they have been slow to accept that. Part of this is decline is demographic, but it is also because of a stagnant economic model. Then there is weak political structure, which appears rigid but is probably brittle in the long run, at least compared with China.

The relationship between Russia and China is based on mutual interest: there is no deep cultural affinity, nor deep knowledge of each other’s nations. But as long as there is external pressure from the West, the two countries will stick together.

The relationship with China also suits many of Russia’s elites in the short term because of what it gives them. All the Russians really want is to be taken seriously as a great power. Allying with China is a way of leveraging that and showing they can be taken more seriously.

One interesting point to note is that President Putin recently gave a speech where he spoke about threats to Russian territorial sovereignty. There is no threat from Europe – Poland isn’t about to march into Kaliningrad – so it’s likely he was talking about China, which is the only nation that poses a threat to Russian land. But this is a rare warning shot to China, if indeed it was.

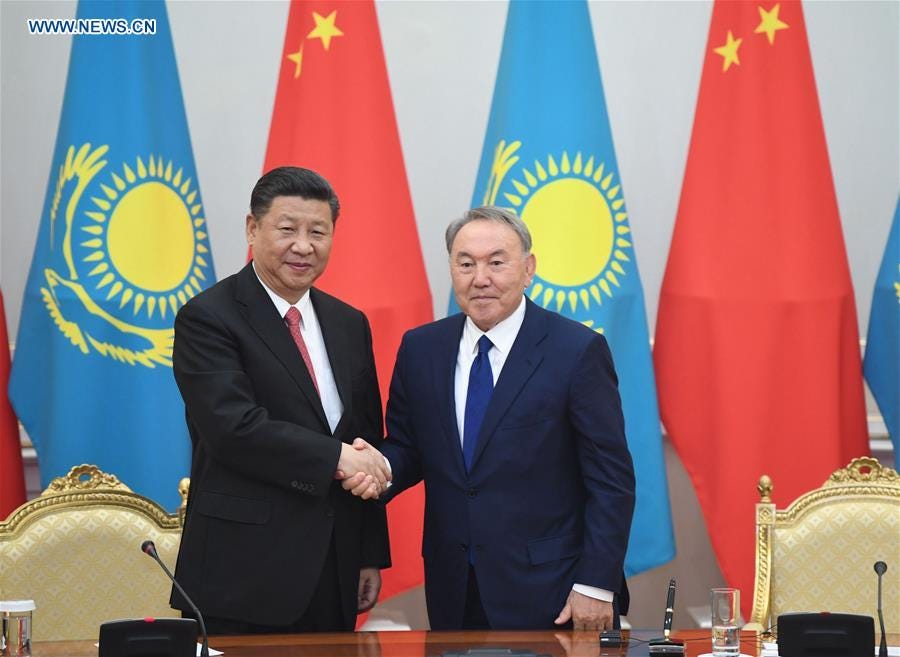

SO: Central Asia has long been Russia’s backyard, but is this changing with China’s rise?

AM: Russia certainly feels that Central Asia is its backyard. There is a very long shared history between Russia and the countries there, like Kazakhstan or Uzbekistan. Even today these nations are run by a generation that grew up in the Soviet Union, and many of the people still speak Russian – more than half in Kazakhstan’s case. Russian soft power, like television, remains strong. There is also a nostalgia for the USSR in some parts, particularly in those areas that haven’t done so well since independence.

The trouble is, Russia doesn’t have any capital to invest, and there is little it can offer the region economically. The one real degree of economic independence is the large amount of migrant workers that come from the region to work in Russia, which as an aside will probably bring about significant social changes to Russia in the long run. But neither side really wants to admit that there is this level of migrant labour; for the Russians it is not good to admit they need the workers, and the public don’t really like having them there – they often have quite racist attitudes towards the migrants. For Central Asian governments, especially for Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan, it isn’t good that they can’t provide jobs for their young people. Nevertheless, it’s happening.

China, on the other hand, has got a lot to bring Central Asia – in theory. There are for example large amounts of underutilised farmland which could be made productive by Chinese capital and labour. But the political fallout from this could be difficult, because there is already a lot of Sinophobia in the region. When, for instance, the Kazakh government announced plans to increase the length of time land could be leased by foreigners from 10 to 25 years there was significant disquiet, with openly expressed fears that they were selling the country out to China.

There are other reasons that China isn’t popular in Central Asia, like the case with the power plant in Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan. Built by China amidst accusations of graft, it broke down in the middle of winter in 2018, leaving the people without heating in temperatures of -27 degrees Celsius.

This is the problem with the Belt and Road Initiative and its interaction with the region. People are suspicious that it’s not really in their favour, and China is just using it to do things like export its pollution. Several cement factories have been opened in Tajikistan recently, which are bad polluters, and there is a feel that Chinese miners have lower pollution standards than Western firms. The problem is, many Western firms are nervous about investing in the region.

Then there is the Xinjiang problem. Not only are there are many blood ties between the Uighurs in Xinjiang and the Kazakhs, there are now half a million Uighurs living in Kazakhstan. In addition, the Kazakh minority in Xinjiang has been targeted alongside the Uighurs for “re-education”. There is a lot of unease about what’s happening in Xinjiang, and many of the stories about the Xinjiang camps that started leaking around 2017 have come via Kazakhstan. Thanks to the situation in Xinjiang, China has lost a lot of popularity across the region.

Overall, the Central Asians are worried about Chinese demographic swamping of the region. There are more and more Han Chinese merchants there, but not yet mass immigration per se.

SO: Could the West take advantage of suspicions about China to invest more in Central Asia?

AM: What’s interesting to note is the fact that the West has good soft power in Central Asia. This is especially true with the education system, which is seen as the gold standard. In terms of creating new educational partnerships the West has a massive advantage in terms of what the local population wants, and this isn’t necessarily in opposition to what Russia is doing.

There is also a respect for the rule of law that is present in the West, which is making itself felt on the ground. In 2018, for instance, Kazakhstan opened up a new financial hub in the capital, Astana, [the AIFC] which it wants to be a global financial centre along the lines of Dubai or Shanghai. To add credibility, the hub’s official language is be English and it is based on English common law. [SO note: the AIFC also has a court and international arbitration centre that is presided over by the former Deputy President of the UK’s Supreme Court, Lord Mance.]

One way to boost their soft power in the region would be to use vaccine diplomacy. China is supplying Uzbekistan with a vaccine, and Russia has sent Sputnik V to Kazakhstan, but it wouldn’t cost much for the UK or US to send over their vaccines there.

SO: There is talk that Russia is fragmenting politically - is this so, and if so, does this make it more likely that China will start dealing with individual regions for example on its frontier?

AM: Keeping a territory together with the area and the poverty of the Russian Federation has always been a struggle, and the country’s rulers are paranoid about it. They always have been, and the Trans-Siberian Railway was built at a time of increased demand for Siberian autonomy so as to anchor Siberia to the metropole.

It is though true that more and more regions, including in the Russian Far East, have slipped beyond the control of Putin’s party in recent years. But it would be a mistake to think that this is a sign of these regions becoming less connected to the idea of Russia.

Instead, it is a sign of a growing impatience in the regions with the incompetence, arbitrariness, and corruption, that is increasingly been seen in Moscow. Many of the protestors, including those that follow Alexei Navalny [the Russian opposition leader] are anti-kleptocrats, and are pushing for the rule of law. This is much more important for them than democracy.

What this means is that the protestors in the Far East are not seeking to break Russia up, because they consider themselves patriotic Russians trying to improve their country. That said, money talks, and the Far East is poor, and so it is a possibility that China may try to make more connections with the regions there.

However, I’m sure that if there was evidence that Beijing was dealing independently with Russian regions like Khabarovsk then Moscow would strongly object.

SO: What can the UK and other Western nations do in the face of increased Russia-China ties?

AM: The main way that the West could try and disrupt Russia-China ties is by showing Russia greater respect, and acknowledging them as a great power. There is great fear in Russia about what they are getting themselves into with their relations with China, and so the West may be able to prize them apart if they did this.

However, the difficulty in doing this is that many countries and NATO members in Europe, like the Baltic States, might feel that they are being sold out. There’s also the fact that Russia is acting like an international troll, and so positive Western outreach might be seen as rewarding their bad behaviour. The main difficulty is that Russia has a zero-sum view of international relations; in other words, if the West is doing well, then Russia must be losing, and vice versa.

For now it seems that Russia and China will be allies – until their interests diverge.