Dear all

Here’s a test for you: try to think of a single Chinese ruler, or in fact a Chinese person full stop, from before the twentieth century. If you can’t do it, then you’re not alone: as I discuss below, China continues to be a vastly under-studied country by the West.

Ask the question the other way round, and you’ll get a very different reply. I have been pleasantly surprised over the years to have found myself in conversations about British culture and history with Chinese men and women, most of whom had never visited the UK. This imbalance of understanding cannot be a good thing in the long run.

As always, if you like what you’re reading then please do share and subscribe - after all, the more knowledge about China the better…

***

At the turn of the last decade I was in my regular Mandarin class when I asked my tutor, a well-educated 23 year old woman from the southern province of Guangdong, what she thought of Europe. She looked at me for a few, drawn out moments, blinked, and replied in a thoughtful voice, “It’s nice, but it’s very small”.

At first glance her words may seem a little odd. Europe is a cultural heavyweight, with a combined economy larger than China’s, and with strong ties to much of the world. Yet what my tutor, Adrienne, was thinking of was the geography and the population. Not only does China have more inhabitants than Europe, North America, and Australasia combined, but it has seven provinces that have a population bigger than France. Three of its administrative districts are geographically larger than Germany.

The obvious point I’m making is that different people have different perspectives. The problem we have in the West is that we don’t make as much effort as we should in trying to understand things from a Chinese point of view. When we do we can be surprised by what we see.

A few months ago, the think tank Pew released a survey which gave some startling facts about what the rest of the world thought of the People’s Republic. A median of 41% across 34 countries surveyed had an unfavourable view of China, with Western countries and their allies being the harshest in their thoughts. A striking 70% of Swedes, and 67% of Canadians, had negative feelings towards the People’s Republic.

With relations between China on one side, and America and its allies on the other, falling to a new low almost every week, it might be expected that Chinese people would share the same negative views of the West. Yet according to some soon-to-be-published research by the British Council, that underrated but highly successful arm of UK soft power, this is not the case, especially when it comes to Britain.

The headline figure is simple: 81% of the young Chinese people surveyed had a favourable attitude to the UK.

The question is, why? Part of the reason is down to the fact that young Chinese know a lot about the United Kingdom. Two fifths of respondees had interacted with the UK, and 19% had visited it. 38% considered the country to be an attractive source of arts and culture, and 45% said they considered the UK to be a good place to study, just behind the US.

And study they do. In 2018/19 a quarter of all foreign students in the UK were from China. With a figure of 120,385, there were more people studying from China than there were students in Wales.

This is not surprising when you consider that Anglophone education has rapidly become a defining status of the middle class in China, whether studied abroad or not. A recent paper claims that nearly 400 million people in China have learnt English to a varying degree, representing 93.8% of all foreign languages students. The next most popular language was Russian (7% of students), then Japanese (2.5%). Just 0.29% of Chinese students learnt even a soupçon of French; for German, it was a mere 0.13%.

Oxford University’s Rana Mitter, Professor of the History and Politics of Modern China, calls this the “great liberal project”. In effect China is sending out hundreds of thousands of its brightest and best from its protected, authoritarian shores, to study in the UK, one of the bastions of world liberalism. This is bound to have some kind of impact on the mentality of at least some of those students.

What’s noticeable is that this study is mainly one way traffic: hardly anyone in the West is learning much about China. Chinese history is not on the mass school syllabus in any Western country as far as I can tell, and it’s not much better with the language. In 2018 3,500 British children took GCSE Mandarin, compared to 250,000 exams taken in French, Spanish, of German. What makes the Mandarin figures worse is that, anecdotally, a large percentage of the 3,500 were native Chinese in the first place.

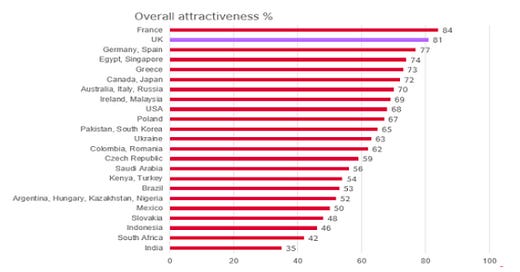

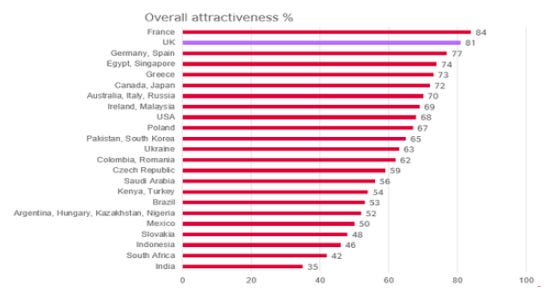

This lack of knowledge about China may be part of the reason that there is such a negative attitude to the country amongst Westerners. The same British Council research revealed that only 41% of young Britons surveyed had a positive view of China, with the country lying in twenty-sixth place, behind Kenya and Turkey.

When it comes to trust, the figures were even starker. 67% of young Chinese surveyed trust the people of the UK, but only 31% of young Britons trust the people of China. 65% of Chinese respondees said they trusted the UK government; only 16% of young people in the UK trust the government of China.

This aligns with the views of G20 nations as a whole and the relatively high levels of distrust associated with the government of China. Given the importance of trust for turning soft power into commercial advantage - a one standard deviation increase in an importer’s trust toward an exporter raises exports by 10 per cent and the level of FDI by 27% - this is troubling news for Beijing.

Of course, it would be foolish to conclude that a lack of exposure to Mandarin is what is mainly driving poor perceptions of China. When the man or woman in the street reads the news coming from Xinjiang, hears the bullying threats from the country’s Wolf Warrior diplomats, and sees the People’s Liberation Army annexing islands in the South China Sea, then it is easy to understand why some foreigners have a hard time in respecting China.

As with every country, not everything about the Middle Kingdom is so black and white. But in order to understand the nuances of the country, its vital to have a base level knowledge of China’s history, people, culture, and language. At a time when China is working so hard to understand the West, it seems strange that we wouldn’t try harder to understand this emerging super-power, and our main strategic competitor.

As an academic told me recently, the last year or so has seen a significant increase in interest about China. Unfortunately, he said, it hasn’t led to an increase in expertise. The British may never come to have as favourable attitude about China as the Chinese do about the UK, but at least we can aim to close the gap by learning a bit more about the place.

Funny !

"Europe is small" meaning that its parts (countries) are smaller than China as a whole...

It shows a skewed point of view or - I'd prefer - an improvised answer to avoid historical grievances that are fueled by nationalist interests (100 years of humiliation) that would have been rude.

It shows even more than Europe is not considered as 1 political entity in in China nor in the UK (for obvious reasons...)