The UK must challenge China’s influence to succeed in South East Asia

Not the easiest of tasks from 8,000 miles away, but possible

Hello fellow China Watchers

This week I’m continuing my look at China’s relationship with South East Asia, specifically at the challenge the UK faces in expanding its influence there when China is already well embedded.

This comes a day after the US upped the pressure in the region by reaffirming its commitment to defend the Philippines from China if Manila was attacked. The Philippines has traditionally been close to the States (it was an American colony from 1898 to 1946) but in recent years the country’s President, Rodrigo Duterte, has tried to open up his nation to more Chinese influence. This has not gone down well with parts of Filipino society who fear that China is trying to take over the country’s seas and islands in the South China Sea: in March this year, a 200+ strong Chinese “fishing fleet” anchored itself over a reef that Manila has long claimed. Like in many of its neighbours, there is now an internal split between those in the Philippines who are pro-Washington, and those who are pro-Beijing.

The question is, can middle powers like the UK take advantage of the increasing divergence between the two camps to provide a third option? This is the subject of my piece below, which is taken from an article published yesterday in the perennial interesting British online newspaper Capx - thanks to its editor John Ashmore.

Many thanks for reading, and do please consider commenting, sharing, and subscribing.

***

In recent years the United Kingdom has made it clear that it views South East Asia as a key strategic priority for engagement. “Any nation with global interests needs to be present and engaged in this region,” said a former British High Commissioner to Singapore, in a speech in 2018. To underline Britain’s focus, in June this year the Foreign Secretary, Dominic Raab, made his fifth trip to South East Asia, where he discussed trade, defence, and security relations with Vietnam, Cambodia and Singapore.

Given the region’s size and potential, it is little wonder that a post-Brexit Britain aims to do more business there. With a population fifty percent larger than that of the European Union, the combined economies of the ten nations that make up ASEAN (the Association of Southeast Asian Nations) have a GDP approximately the same size as the UK’s, but their growth rate – 4.6% in 2019 – has been substantially higher in recent years than either Britain’s or the EU’s.

London has not been idle in stimulating its links there. Pushed by an ambitious Department of International Trade, digital economy agreements have been signed with Singapore and Vietnam, with further deals being negotiated. In addition, hundreds of millions of dollars of aid and investment have been announced in recent years, including $132.5 million through the government’s Newton Fund to support international science and innovations collaboration in the region.

Diplomatically, London has been active too, establishing a mission to ASEAN in 2019, as well as launching formal negotiationsto join the pan-Pacific CPTPP trade block that many South East Asian nations belong to. Militarily, the British presence has been beefed up in Singapore, and to underline the UK’s resolve in the region, the HMS Queen Elizabeth Carrier Strike Group (CSG) is due to sail through South East Asia in the coming months.

But as the Royal Navy will find when it navigates through the disputed South China Sea, British ambitions in the region will butt up against the interests of a power that has, in recent years, been making strenuous efforts to build its influence in South East Asia. China – which is now classified as a strategic competitor of the UK – has spent years and billions of dollars courting the nations of the region, creating strong trade links and securing political sway, its efforts helped by the structural advantages that it has through its history and demography.

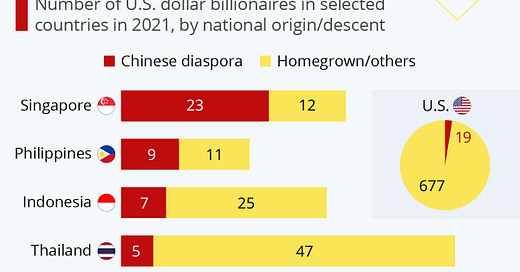

China has been trading with South East Asia since at least the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907), and after centuries of emigration, there are between 30 and 40 million ethnic Chinese living in the region, with majorities or sizeable minorities in Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand. It is a flow that hasn’t yet stopped: an estimated 700,000 Chinese nationals emigrated to Cambodia alone between 2014-2019. By contrast, there are probably well under a quarter of a million Britons living in the whole of South East Asia.

What’s more, whilst British expatriates tend to work for multinational firms and are more often than not temporary residents, the Chinese diaspora has a firm grip on much of the economic activity of the region. This is something that Beijing has been keen to capitalise on, with government influence campaigns being targeted at the Chinese elites of many of the nations there.

The People’s Republic has also been investing heavily in developing its economic ties with South East Asia. This has tended to focus on expanding its supply chain, partly because of rising labour costs in Chinese own factories, but also as an unintended consequences of President Trump’s trade war. Chinese firms, seeking to avoid tariffs that the US has imposed on China-made goods, have spread out to countries like Vietnam and Indonesia, pushing land prices through the roof and establishing Chinese businessmen and women as local big-hitters. Thanks to Beijing’s actions, ASEAN is now China’s largest trade partner, with trade hitting $731.9 billion in 2020.

On the surface, the UK might be considered to be an also-ran when compared to Chinese influence there. For example, British trade with ASEAN in the four quarters to the end of Q3 2020, at £36.4 ($45.5) billion, was just six per cent of that of China.

But this would be to miss a critical part of the story, namely that there is distinct unease in the region about growing Chinese influence there. A poll carried out earlier this year by a Singaporean thinktank revealed that whist China was considered by a clear majority of respondents to be the most influential economic and strategic-political force in the region, more than seventy percent considered that to be of concern. In a binary choice between the US and China, only three of the countries surveyed had a pro-China majority.

In theory this provides the UK with the opportunity to become a third trusted partner for those countries looking for an alternative to Chinese or American influence. Britain has a number of structural advantages that make it a strong candidate to fulfil this role. It has long-standing historical ties with the region, and its cultural links remain very strong: tens of thousands of ASEAN studentspast and present have studied in the UK, including many regional leaders. Not only that, but Common Law anchors many contracts, and English is the lingua franca. Britain is also one of the leading sources of foreign direct investment (FDI) into ASEAN, investing £6.9 billion in 2019.

However, despite all this, London faces an uphill battle to become a strategic partner of choice. In the same Singaporean thinktank poll, only 3.7 per cent of ASEAN respondents said that they would look to the UK as a preferred strategic partner, compared to 19.3 per cent for the EU and 36.9 per cent for Japan.

This does not mean that the situation is hopeless. Indeed, it can’t be, because the UK’s goal of becoming the “European partner with the broadest and most integrated presence in the Indo-Pacific” will be impossible without securing more of a presence in ASEAN nations.

It can be argued that China’s success in the region means that it will be harder for the UK to make as many in-roads as it would perhaps like. But given time, and Government-backed support, there is no reason that the UK cannot build upon its structural advantages to become a leading partner to the region, to the mutual benefit of all.