The threat to IP: when governments and the private sector collude

It's not just China that has history here

Dear all

Last week we looked at how Western intellectual property is reportedly being plundered by entities within China at a staggering scale. Yet no country is perfect. For years there has been talk of the French government bugging business class passengers on Air France flights to glean trade secrets, and Russia is known to grab what it can (including, so it is reported, an attempt to steal the UK’s Covid vaccine). As I discuss below, America also has form here, albeit a long time ago.

It is China though that leads the way in combining public and private sector efforts when it comes to creating economic advantage, and that’s what we will explore this week.

In the meantime, please remember to share, like, and subscribe. Thanks!

***

Amidst the hoo-ha generated over the last few years regarding China’s reported wholesale theft of intellectual property (IP), it is worth remembering that America itself has not always been snow-white when it comes to purloining trade secrets.

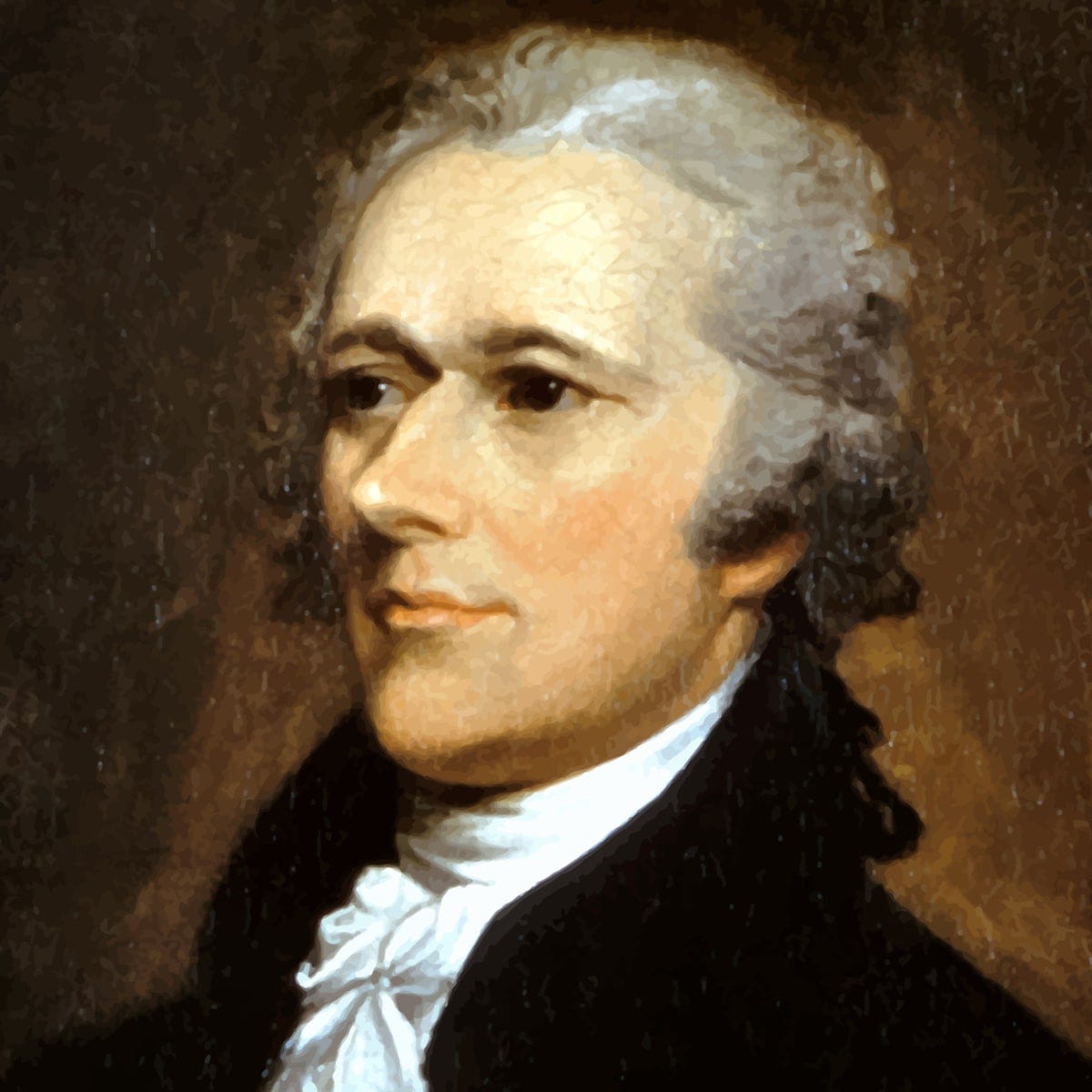

It was Alexander Hamilton, the Founding Father and current theatre sensation, who recognised shortly after the Declaration of Independence how the fledgling United States would remain vulnerable so long as it didn’t industrialise. Hamilton accordingly sent a number of agents over to England, then the leading industrial power, to steal machinery plans on behalf of the nation.

The British authorities knew that this was happening, and did have some success in stopping the theft. In 1787, for instance, American agent Andrew Mitchell was intercepted as he was trying to smuggle new technology out of England. Inside his seized trunk were models and drawings of British textile machines, which were to be taken back across the Atlantic and copied.

Not all the theft could be prevented, however. A large part of America’s first wave of industrialisation, particularly in textiles, was forged from stolen IP. Indeed, huge fortunes were made on the backs of British inventions. The first man to establish a cotton factory in the US, Samuel Slater, took the trade secrets from a British cotton factory. When Slater died his net worth amounted to one tenth of a percent of the country's gross national product.

America’s charge

Knowledge of its past has not prevented America from going after China in an effort to stop what has been called “the greatest transfer of wealth in history”, as I wrote about last week. In 2014 the US Attorney General accused a group of five Chinese hackers of carrying out a high-tech campaign of electronic burglary against prominent American businesses like U.S. Steel and Westinghouse Electric. Despite teenage sounding names - like UglyGorilla and KandyGoo – these hackers were accused of being soldiers from Unit 61398 of the People’s Liberation Army, operating from a non-descript office building in Shanghai’s Pudong district.

Whilst this case was quietly dropped, the US’s determination to stop Chinese state hacking of American IP remains strong. In February 2020 members of the US government held a conference to discuss the plague of thefts suffered by North American companies and academic institutions. The conference opened with a strong statement by John Demers, the Assistant Attorney General for National Security: “The threat [of IP theft] from China is real, it's persistent, it's well-orchestrated, it's well-resourced, and it's not going away anytime soon”.

FBI Director Christopher Wray said that he believed that Beijing’s efforts to take American IP represented “the greatest long-term threat to our nation's information and intellectual property, and to our economic vitality.” The FBI, continued Wray, were examining about a thousand cases involving suspected Chinese involvement in the theft of US-based technology in all fifty-six of their field offices, and spanning just about every industry and sector.

The FBI believes that this theft is being directed top-down by the Chinese authorities, part of the national effort to rejuvenate the country by fair means or foul. The list of targets includes military equipment, and the latest stealth technology. On a visit to Ukraine in 2019 the then US Defense Secretary John Bolton said of the new Chinese J-31 plane, it “looks a lot like the F-35, that’s because it is the F-35. They just stole it”.

As the F35 is the backbone of the future air abilities of not only America, but the UK, Japan, Australia, and a host of other Allies, if China has acquired the technical readouts of the plane then it puts both Western air crew and Western air superiority in potential danger.

Always intertwined: the Chinese state’s relationship with its private companies

The charge laid by the Americans is that the Chinese government is actively helping to steal American and Western IP. This in turn asks a deeper question: to what extent are Chinese companies free from Beijing’s power?

The recent tale of Jack Ma shows how easy it is for the state to crush an individual, even one as powerful as the Alibaba founder. It could though be argued that Jack was a one-off, an attempt to pull him back into line after making such an inflammatory speech that made the global headlines because of who he is.

It would be wrong to think so. As Beijing has made very clear over the years, every company in China is susceptible to the demands of the State. Not that everyone wants to admit it.

“Huawei is a private company. The Chinese government does not have any ownership or any interference in our business operations.” So said Huawei’s senior comms officer, Joy Tan, in an interview with Forbes magazine in 2019. This was in the middle of the fierce campaign being waged by between the Trump Administration and the Chinese technology giant.

Huawei’s assertion that they are completely independent of the Chinese government is not entirely accurate. Even if no shares are owned by the state, as the company claims, under China’s legal system the Communist Party’s word is its command, and indeed there are precise laws that could be used to force Huawei to do the CCP’s bidding. The 2017 National Intelligence Law for instance declares that Chinese companies must “support, assist, and cooperate with” China’s intelligence-gathering authorities.

Many businesses do not try to hide their connections to the CCP. As The Economist has noted, more and more Chinese companies are citing President Xi Jinping in their annual reports – almost 400 in 2020, up from only a handful in 2015.

Declarations of public allegiance aren’t a guarantee of being left alone, however. In 2015 China’s Ministry of Public Security announced that police would be placed into the offices of major Internet companies, most of which had been loyally active in helping China’s expansion at home and abroad. A board member of one of the leading Chinese technology companies told me at the time how their staff had arrived at their office one morning to find it full of uniformed police, who then took position at every internal corner. They didn’t do anything (at least that was mentioned to me) except make their presence felt amongst the employees: an expression of power not to be ignored.

Quite simply, everyone in China is forced to support the country’s leadership in its great national rejuvenation project. In return, the government will support companies for their own economic ends. Often this is financial or regulatory assistance, and many of the country’s tech giants have benefited from protection from outside competition within China’s borders, as well as cheap subsidies for export abroad.

What the Chinese authorities also do, it is alleged, is to help acquire trade secrets from rivals. And it is America which is leading the charge against this activity.

Putting present above past

There are though those in America that are uneasy about Washington’s role in trying to stop China, given the country’s history. “Knowledge of America’s history in hijacking intellectual property should at least soften the rough edges of criticism of China,” declared the late writer Allan Golombek.

Perhaps. What observers like Golombek don’t necessarily consider is that the stealing of IP is not some ephemeral, academic construct that has limited fallout. It is, instead, a direct assault on the economic capabilities of both companies and countries, and one which has real consequences for the wellbeing of tens of millions of individuals.

Next time we will look at exactly what we mean by this - including the story of how Chinese activities most likely destroyed one of the West’s leading technology companies.