Dear fellow China watchers,

Welcome back to the culture and history thread of What China Wants. I’ll be returning to our History of China soon, but today I’m going to discuss one of the books I recommended for summer reading. Broken Wings by Jia Pingwa, translated by Nicky Harman. The book discusses a tragic social issue that is not spoken nearly enough about: the trafficking of women and girls in China.

One of the catastrophic effects of China’s One Child policy, which officially ended in 2015, was widespread female infanticide. Whilst the killing of baby girls was not a new thing in China – eighteenth and nineteenth century missionaries wrote about the phenomenon – it’s certain that the One Child rule led to a spike in the practice, with deleterious effects on the country today.

Couples who had a little girl often chose to kill her (either directly, through exposure, or by starving and maltreating the baby) so that they could try again for a boy. The reasoning for this infanticide - which is said to still happen today - is hard for us in the West to fathom, but it is generally understood to have been because girls required more resources than the parents would ever receive back. Not only could girls not do the heavy agricultural work in the fields, but they also needed a dowry of some sort to marry them off.

The result is that there are 30 to 60 million extra men in China, men who will never have a chance of marriage. To put this in context, this is at a minimum the same amount as the total number of males in the UK, and at a maximum the same amount of all the men in America between the ages of 20 and 60.

Not surprisingly, this gender imbalance has led to a number of societal problems in China, such as heightened violence and drug-use, especially in its third-tier cities and below. The doubling of China’s crime rate from the mid-1990s onwards has been attributed by some as being a direct result of the One Child policy.

Perhaps the most insidious consequence, however, has been the rise in the trafficking of women. It is a trade that has blossomed to satisfy the natural demands of these extra men, but it is not just about sex. As has been explained to me by Chinese friends on many an occasion, China is ancestor obsessed, and not having children to continue the family line, and to think about you as an ancestor, is a major social worry.

The scale of human trafficking in China is hard to quantify, but it is pronounced. Forced labour is of particular concern, such as in brick kilns and factories, and in 2013 it was reported that each year tens of thousands of children were abducted to feed the forced labour market.

But it is the trafficking of females that Jia Pingwa’s book deals with. Chinese girls, and women too, are often recruited from rural areas with the false promise of a job, then sent to urban areas where they are forced into prostitution or marriage. Females are also brought in from abroad – Pakistan, Burma, Vietnam, and elsewhere - at a scale unknown, but according to work I did with a human trafficking charity in 2015, the number could be in the thousands, maybe the hundreds of thousands, each year.

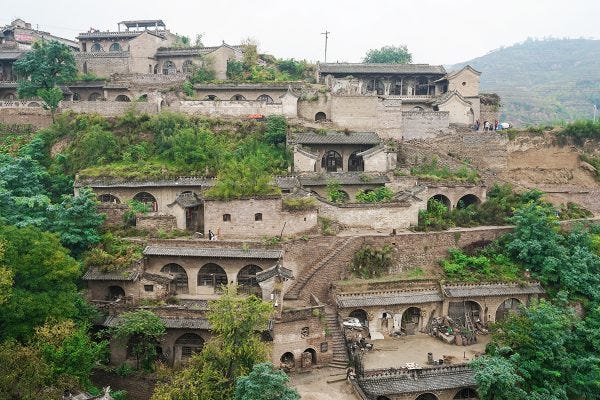

Broken Wings, which is inspired by a true story, brutally deals with this evil, but in reverse to what might be considered to be the “norm”. Butterfly, the protagonist, is an urban girl who is kidnapped and sold into sexual slavery in a remote mountain village, where she is kept in a cave. Written in the first person, the novel begins on the 178th day of Butterfly’s captivity.

The stated reason for her abduction is not just that the men, including her new “husband”, are desperate for wives for their own satisfaction. It is also that the villagers together, women included, want to see the village continue into a new generation.

At first Butterfly struggles hard against her imprisonment. But after she becomes pregnant, her attitudes to the village and to her past life begin to change. It is this change that shows Jia is writing not just about the injustices around trafficking, but fundamentally questioning what it means to be Chinese today. (There are a few spoilers below, but it shouldn’t detract from your reading of it – I hope.)

The form and location of Butterfly’s prison is probably not a coincidence. In Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, which he presents in his work The Republic, a group of people have been imprisoned in a cave and forced to face a wall. Behind the prisoners is a fire, and between the fire and the prisoners are people carrying puppets or other objects. The light from the fire casts shadows of these objects onto the wall, which the prisoners watch and come to believe are real.

Then, when a prisoner escapes from the cave – as Butterfly eventually does – she realises that what she perceived in the cave is not actually real, but a perception. The other prisoners, worried that they will be harmed by the real outside world, subsequently refuse to leave the cave.

This, in a nutshell, is what happens in the book: Butterfly comes to realise that she prefers to see the images of modern China on the wall, rather than feel its reality in the flesh. This is a question that many of the quarter of a billion internal migrants in China – most of them moving from rural to urban – are forced to ask themselves on a regular basis, and it shines a light on the torment that many must feel.

Not surprisingly for a country that doesn’t like to look too hard at its internal challenges, Jia received plenty of criticism for the book. But as an insight into the terrible reality of what it is like for far too many in China today, it is critical reading.