The Prophylactic Properties of Wall Street's Exposure to China

Why Beijing wants to encourage US investment

Hello and welcome to What China Wants.

There’s been a great deal of discussion about the issues facing China’s economy recently, including the power outages I examined a couple of weeks ago. Despite this, Wall Street’s appetite for investment in the People’s Republic doesn’t seem to be dampening, which many might find surprising given the rising political risks emerging there.

The question is, what is driving this? And why can’t the Wall Street bosses see what many China analysts can? I examine some of the reasons below, and discuss how this is playing exactly into Beijing’s hands.

As always please feel free to comment, like and share. Many thanks for reading - and I’ll be back on Saturday for more from the History of China.

***

Donald Trump’s presidency was noted for a number of things, but the one most relevant to this newsletter was the step-change in official American attitudes to China.

When I was working in the American Senate in 2004, analysing allegations of Chinese steel dumping into the US market, we were told by the White House that if we made too much of a fuss about Chinese economic infractions then this would have a negative impact on China’s political liberalisation. In other words, if we ignored deleterious trade practices then this would facilitate China’s democratization.

Any such thoughts have long been abandoned in Washington, and Trump made sure that Beijing knew it. The trade war launched in 2018 was one manifestation of this new robust thinking, but there are others hovering in the background. The fact that they are so far unseen is unsettling to the CCP – as it would be for any government – because America still has the power to make life very difficult for countries, even China.

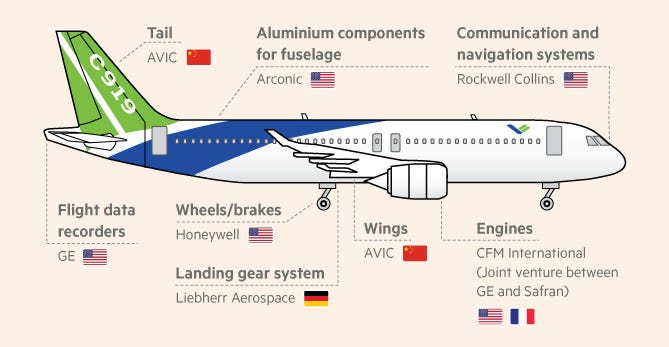

It already has. The blacklisting of Chinese companies by the US, which President Biden has continued, is being blamed for a variety of business issues inside China. For example, the placing of China’s airline manufacturer, Comac, on the blacklist has made it more difficult for the company to acquire the parts it needs from American suppliers. The resultant lack of spares could inhibit the ability of the company to gain a foothold outside of China, experts argue.

The trade war and the blacklisting are serious steps taken by America to limit China’s ability to challenge Washington, but there are concerns that they won’t make too much of an impact in the bigger scheme of things. Indeed, there is an argument that the US has been more hurt by the trade war than China.

It is highly unlikely that a next step on the escalation ladder would be anything other than truly painful, for China for sure, and America maybe. This is full-on financial war in the form of a dollar blockade.

China needs dollars for a variety of reasons, including paying for the energy and food it imports. Oil spend alone in 2019 was approximately $160 bn, and the total for food in the same year was $105 bn. It also has foreign debt of around $2tn in a mixture of currencies, including the greenback.

Dollars are also needed to provide hard currency backing to the RMB money supply through reserves - something that the plutocratic class of Chinese investors have a strong preference for when there is no other backing for the yuan other than the reputation of the Chinese Communist Party.

American dollars are also needed to finance China’s economic expansionism, for example through the Belt & Road Initiative, or the Digital Silk Road. Huawei and its brethren charge their international clients for the most part in USD, which means that they have to take significant hedging positions that would be severely hit by a dollar blockade.

That said, any immediate pain from a dollar blockade would be cushioned by the $3.2 trillion of foreign reserves that China holds. But these wouldn’t last for ever.

China is not blind to the threat. They have been preparing their plans for a while now, and have established a number of defensive ditches.

The Dual-Circulation Strategy is one of these. What DCS does, in effect, is push China down the road towards autarky, by restricting its exposure to foreign companies and expertise. If it is successful (and it’s a bit “if”), DCS should reduce the risk of the country falling foul to further US economic sanctions.

There is also the internationalisation of the RMB, which continues apace mainly through efforts to establish a digital currency. Although the Chinese authorities reckon this will help boost the acceptance their currency abroad, it is not without its risks, including facilitating a major outflow of capital from China.

Perhaps the most eye-catching defence though is Wall Street.

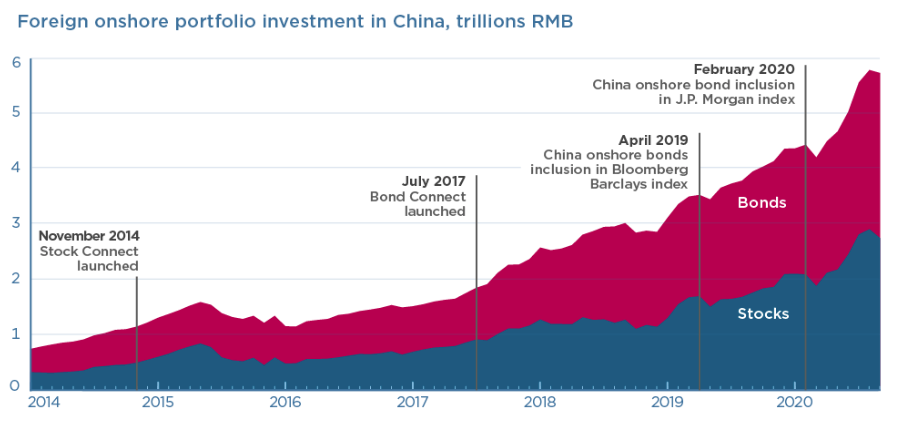

Recent articles have suggested that American investors, rather than being spooked by the sharp decline in governmental relations, are doubling down on China. According to Morningstar, the financial services firm, American mutual funds and exchange-traded funds investing primarily in China held $43 billion in net assets at the end of August, up 44% from 12 months earlier. This included $13 billion in new money added by investors.

Bonds are in favour too. By the end of September this year, China’s central government bonds held by foreign investors reached nearly 2.28 trillion yuan (about 354.11 billion US dollars), up by 77.12 billion yuan from the previous month, according to official data.

Overall, the picture is of increasing financial integration, being driven in great part by American investors.

Wall Street’s stance is a puzzle to the many who see the political issues within China to be a direct threat to their operations there. The country is in the middle of what has been dubbed a “Red Reset”, or a return to hardline socialist principles which has seen one industry after another targeted for “re-education”. The fact that this includes the real estate sector, which until recently was thought too big to challenge given that it represents a quarter of GDP, has not worried some foreign investors: both JP Morgan and Goldman Sachs have recently reaffirmed that China is investable.

As Stewart Paterson, an analyst of China’s economy and the author of China, Trade, and Power, thinks there are a number of reasons why Wall Street institutions remain bullish.

First, is that they have invested a lot of emotional capital in explaining how China will be the next big thing, and to pull out now would be embarrassing. Second, China has been profitable at times, which means that the institution’s internal China analysts have weight when it comes to looking for future returns.

Thirdly, not many of these institutions’ clients understand China, and in particular the political risks that seem to be rising each week, and so there is not much pressure on them to disinvest.

As the writer and activist Upton Sinclair once said, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it”.

This is good news for the CCP. The more skin in the Chinese game Wall Street has, the more it will complain about any moves Washington makes to wage financial war on Beijing.

Many of its institutions have strong links to the Biden Administration, like BlackRock, whose former investment executive Brian Deese leads Biden's National Economic Council, effectively serving as his top advisor on economic matters. Larry Fink, BlackRock’s CEO, was at one point tipped to be Treasury Secretary under Biden, an appointment that Beijing was no doubt keeping an eye on: Fink is a well-known advocate of the economic possibilities of doing business in the Middle Kingdom. “We are here to work with China,” he said to a forum via videolink in June last year. The feeling is mutual: in 2015 Fink was brought in by Beijing to advise on how to handle market volatility.

China’s rapid recent changes have made it a more volatile, more difficult place to do business, as Jack Ma, the semi-purged billionaire would attest to. The clouds hovering over business confidence in China, not helped by the recent state-ordered power outages ahead of the COP26 talks in the UK next week, are darkening with time.

But still US financial investors remain bullish. This is either Trumpian-style hubris about the power of finance to out-manoeuvre politics, or they know something the rest of us don’t. Either way, Wall Street’s activities fit very nicely into Beijing’s defensive plans - although whether it will make a difference in the end is anyone’s guess.