The Asymmetry of Chinese & Western PR

China is outsmarting the West when it comes to making use of the media

Hello fellow China Watchers,

First of all, I’d like to welcome the enormous number of you who signed up to What China Wants following my interview with Kishore Mahbubani last week. Please do feel free to comment on my posts and get the conversation going.

I’m in the middle of moving so won’t be writing a full dispatch today; rather, given what’s happened with the Hong Kong pro-democracy newspaper Apple Daily in recent days, I’ll be making a few observations about China’s use of PR in the wider world.

It’s a fundamental fact that at almost every level, there is an asymmetry of communication between China and the West.

Politically and diplomatically, Chinese diplomats have long enjoyed almost unfettered access to Western media channels, including social media, and using platforms like Facebook which are banned in their home country. Their PR outreach is a professional and well-coordinated propaganda campaign that uses every channel possible, for example paying Western social media influencers to produce pro-China videos. Chinese officials make frequent use of op-eds in Western newspapers to get their messaging across, and the braver ones allow themselves to be interviewed on the news.

Western politicians, on the other hand, struggle to get their message across in state-controlled publications in China. Op-eds are almost non-existent, and posts that aren’t in line with CCP messaging are either inundated with messages decrying the Western poster, or they have their “share” buttons disabled.

This digital divide was brought to the fore recently by the travails of the new British Ambassador to China, Caroline Wilson. (Disclosure: I met Caroline a number of times when she was the Consul General to Hong Kong, and she is as smart and amiable as can be.) In March this year she published an article on the China social media channel WeChat, saying that just because journalists criticised China it didn’t mean they hated the country. Instead, they were doing their job in keeping governments to account. The result was that she was summoned for an official reprimand by the Chinese authorities. Beijing’s then Ambassador to London, Liu Xiaoming, was particularly scathing that she would do such a thing, despite the fact that he had written more than 170 pieces for the mainstream British media during his tenure.

Things are changing, however. As China-Western relations have plunged in the last few years, there has been an appreciation of the impact of Chinese PR activities and the need to rein them in if balance is to be created.

In January this year, Twitter locked the account of the Chinese Embassy in the US over tweets it made on the Uighurs, and in 2020 it banned around 200,000 accounts linked to the Chinese government over concerns that the CCP was using them to spread its propaganda. Then in February, the UK regulator stripped the Chinese state news channel CGTN of its licence, citing its links to the government in Beijing.

In return China is clamping down on anything that can be seen as potentially seditious. In 2020 Beijing banned thirteen US journalists, and two more from Australia were rushed out of China over fears they would be arrested – one of them, Bill Birtles, had been told by the police to come in for questioning over a vague “national security case”. Other journalists have had their visas revoked or not renewed, and BBC News has been banned in the country. Abroad, Chinese diplomats have threatened and punished news outlets for reporting what they don’t like: in April a journalist in Sweden received an email from the Chinese embassy accusing him of “moral corruption” and telling him to cease his Beijing-critical coverage or “face the consequences of your own actions”.

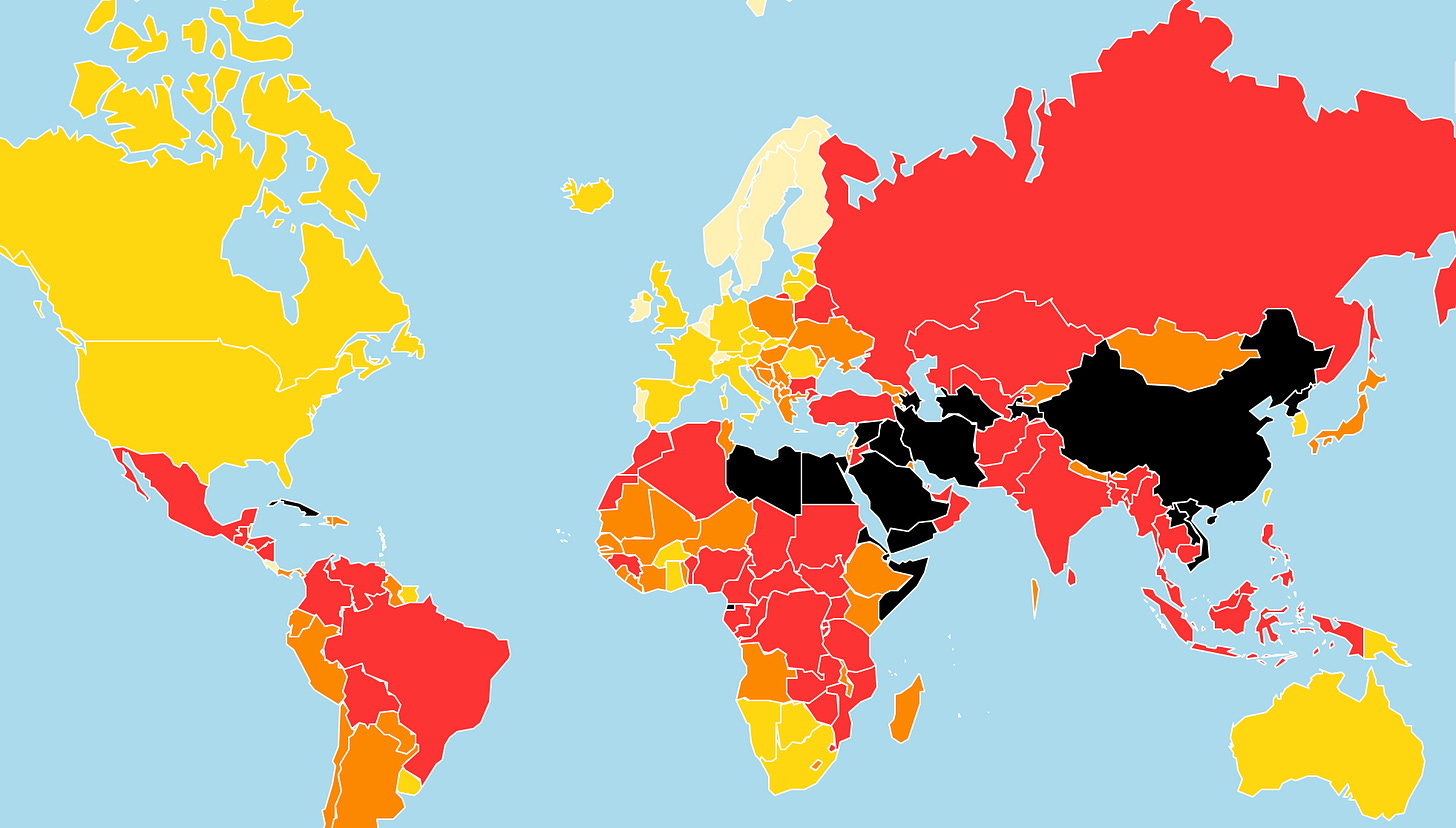

It is little wonder that in 2021’s World Press Freedom Index, China comes 177/180 countries - a couple of spaces above North Korea, but below Iran and Cuba.

Given this, it is more of a surprise that it took so long for Apple Daily to be shut down.

But the timing of the paper’s demise means that it won’t be running any anti-communist stories ahead of a highly anticipated event in Beijing, the 1 July centenary of the founding of the CCP. Ahead of the celebration, a dramatic nationwide media campaign has been launched, aimed at cementing the validity of both the Party and the President, Xi Jinping.

Unfortunately for fans of the kitsch, the CCP haven’t commissioned any comedy cartoons as they did to popularize the latest Five-Year Plan. Instead, the videos have been more stoic in tone, such as this one from Shanghai, the birthplace of the Party.

The mood of these latest videos is much more in line with how important Beijing takes its communication strategy, both internally and externally. The West has traditionally been much more laissez-faire about the media, and although there are frequent criticisms about its independence, the Fourth Estate in Western Europe, North America, and Oceania has long prided itself as being separate from the state. This is certainly not the case in China, as Apple Daily has found to its cost.

The Developing World is slowly waking up to the fact that China is using the West’s own media tools to challenge the Western world order. Given the power of the press, and social media in particular, this is a front in the increasingly fraught competition between the two sides that Western leaders need to pay much more attention to, and fast, if they are to successfully counter China’s global narrative.

I’ll be back next Tuesday with a special newsletter covering the CCP’s centenary, and look out for my latest History of China post this coming Saturday.

Many thanks for reading.