Dear all

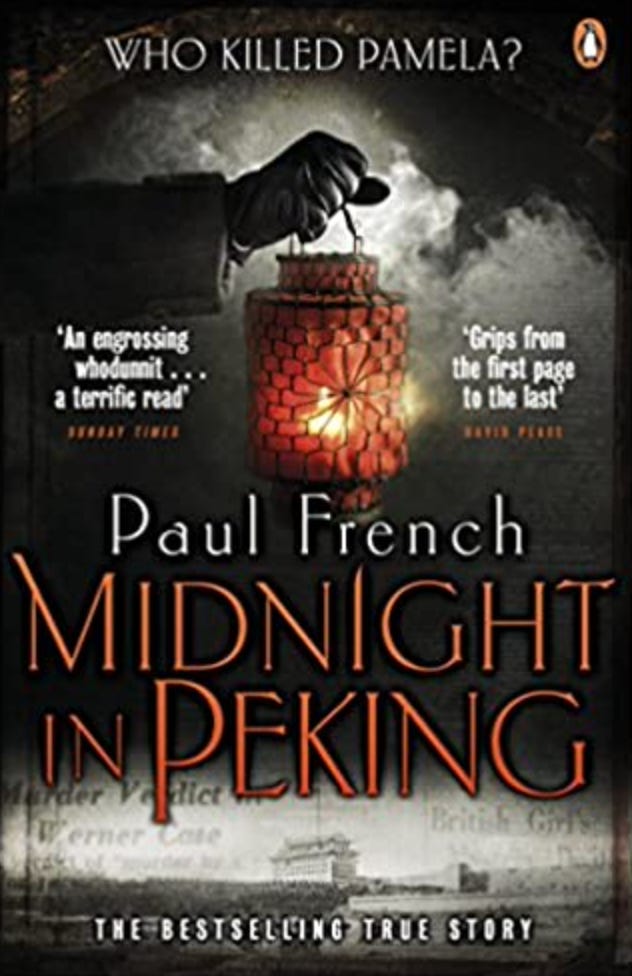

Continuing on the theme of Chinese culture and history, today I’m combining them with a few words about one of my favourite books about China, the award-winning Midnight in Peking, by Paul French.

The true story centres on the murder of a British girl in what is now the Chinese capital, Beijing. On the morning of 8 January 1937, the body of 19-year-old Pamela Werner was found at the foot of one of the towers that were scattered along the old city walls. All the blood had been drained from her body, and her heart had been removed.

The murder sent a chill through a city already made nervous by its encirclement by the Japanese army, which had been fighting in China since 1931. Two detectives, one British and one Chinese, set out to find Pamela’s killer amidst a fog of rumour and superstition, rushing to close the case before war erupted and their way of life was lost forever.

Beijing in 1937 was very different to the one today. It wasn’t even called Beijing for a start, but “Beiping”, which means “northern peace”. (“Beijing” means “northern capital”, but at this stage the city had lost its status to Nanjing “southern capital”, and so it had been renamed.)

It was a city of scholarship, of ritual, and of traditional architecture, and, like the country as a whole, bubbling with turmoil. A quarter of a century had passed since the overthrow of the last Emperor, and although the Republic of China was theoretically in charge, their power was built on sandy foundations. The 1930s saw countless political murders in Beijing, as enforcers from the ruling party (the Kuomintang, or the Nationalists as they are also known) clashed with both the communists and the turncoat Chinese who were ready to serve the Japanese if and when they conquered the capital.

In the midst of this Chinese disorder lived tens or hundreds of thousands of foreigners. Shanghai has the reputation of being the international city, but there were plenty of non-Chinese living in the capital too. Some were diplomats and merchants nestled around the Legation Quarter, on the edge of the Forbidden City, which had been a centre of foreign residency since the UK forced its establishment at the end of the Second Opium War in 1861.

Many of the other foreigners were far lower down the social scale. They were waifs and strays from all over the world, gamblers and drinkers, thieves and the honest poor, including countless White Russians banished after their loss against the Bolsheviks. French describes how one such Russian man slit his wrists at the same spot beneath the city walls that Pamela was found, next to the reportedly haunted Fox Tower, no doubt driven to suicide by the forlornness of permanent exile.

All of this was to change over the coming decades of Communist rule.

China under Mao was not much of a place for a foreigner. Within a couple of decades of 1949 most of them had left, either voluntarily, or exiled by the Party. Whilst there aren’t any exact figures to compare the percentage of aliens then and now, what is certain is that it wasn’t until the 1990s that people from outside of China started to return in anything like the pre-War numbers.

Beijing’s buildings didn’t fare much better. The 24km-long city walls that had stood since 1553 were pulled down in the 1960s to make way for a ring road and the Beijing subway.

The Cultural Revolution (1966-76) also destroyed vast swathes of the city. The China writer Ian Johnson has described how, when he was living in Beijing in 1984, he played a game whereby he’d look up important cultural sites mentioned in a 1937 book, Nagel’s Encyclopaedia Guide to China. Not many were left. Streets in Beijing are very often named after their relationship to things that no longer exists, “ghostly landmarks” as Johnson puts it. This of course is the same in cities all over the world, but the recentness of the destruction makes it more pointed.

It isn’t just the landmarks from Pamela Werner’s time that have gone. Many, perhaps most, of the old hutongs have been swept away too. Hutongs are the narrow lanes between courtyard-centred homes that at one time radiated away from the central Forbidden City, with the owner’s social status indicated by the residence’s proximity to the centre of the celestial kingdom.

Unesco estimates that 86 per cent of the hutongs have been destroyed, ripped down to make way for motorways and towerblocks. When I first visited Beijing in 2004 the locals advised me to spend some time in the hutongs, which thankfully I did. Some of them were down-at-heel, with dirty communal toilets and grimy children wandering the lanes. When I returned to a similar spot in 2011, I found the hutongs and their buildings had been converted into Western-style cafes and chintzy art galleries where smiling images of Chairman Mao mingled with plastic anime cats. It’s up to the Beijingers to say which they prefer.

Midnight in Peking brings to life the Beijing of old, wrapped around a tightly crafted mystery plot that French hopes brings some conclusion to the life and death of Pamela. With the Chinese state now monitoring the minute by minute lives of much of their population, there’s not much chance of a similar mystery being written seventy years in the future about any unfortunate woman murdered today.