China, Military-Civil Fusion, and Overtaking America

How Google (again) helped China rather than its home nation

Dear all,

I was invited to give a talk to an Asian based forum the other day about Western-Chinese relations, and in particular what the potential was for conflict in the short to medium term. The answer, as I have written about here, lies with Taiwan. It is absolutely critical to the success of the Chinese Dream that Taiwan is reunited with the Motherland, and if they won’t come peacefully, then there’s always the People’s Liberation Army solution.

Yet an invasion of the renegade province won’t be easy: crossing a 100 mile strait in the teeth of American opposition would make D-Day look like a stroll down Main Street.

No wonder, therefore, that Beijing is so keen to modernise its Armed Forces. To do so they have established a programme called Military-Civilian Fusion, based - ironically - on the secret to Western success over the last two centuries. In today’s newsletter we will explore what Military-Civil Fusion is, and why it’s hard for the West to copy China’s success.

Please remember to like, share, and subscribe. Many thanks for reading.

***

On 12th November last year President Trump signed an Executive Order that banned Americans from doing any sort of business with a group of named companies suspected of helping the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Many of the names on the subsequent blacklist are, at first glance, more civilian rather than military: Xiaomi, for example, makes cheap mobile phones.

Dig a little deeper, however, and it becomes hard to tell the difference. The reason is that China has developed a highly sophisticated blurring of the two to create what is known as “Military-Civil Fusion”, or MCF.

In short, Beijing has realised that the key to developing its military, intelligence, and other security apparatuses is the country's large, ostensibly private economy. As the US has noted, MCF leverages China’s economic strength by compelling civilian Chinese firms to support the development of its military, security, and intelligence apparatuses.

As Washington realises, MCF is critical to China’s future, specifically in terms of it achieving the Chinese Dream of becoming a great power. As President Xi said in 2017, China will “deepen reform of defence-related science, technology, and industry” and "achieve greater military-civilian integration” with the aim of making the military fully modern by 2035.

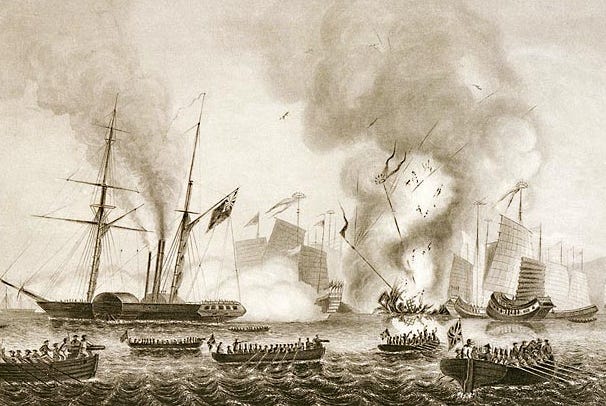

This is not the first time that China has attempted to blend its military and civilian development. That came in the wake of the Opium Wars of the 1840s and 1860s, when British naval forces showed what could be achieved when bringing both together. In the First Opium War the Royal Navy was led by the ironclad HMS Nemesis, a tangible, deadly outcome of military ambition tied to British civilian ingenuity in coal mining, steam power, and metal-working. The ship was more or less invincible against the wooden, and in some cases pedal-powered craft of the Chinese Imperial navy.

The Qing Empire saw that the British had harnessed the economic power of the state to create war-winning technologies, and so tried to replicate this, for example by opening up coal mines linked by railways that could power both factories and naval forces. Unfortunately for the Empire, for a variety of reasons (conservativism, corruption) this initiative didn’t work, as was shown in 1895 when thoroughly modernised Japanese forces smashed China in a short, sharp war.

Further evidence as to the benefits of combining the military and the civilian have been shown time and again by the West.

The Battle of the Atlantic, if not the entire Second World War, was a victory for Anglo-American inventiveness. The German Admiral Dönitz, his forces mostly scattered on the seabed at the end of the struggle for the Atlantic sea-lanes, wrote that “the enemy has rendered the U-Boat war ineffective. He has achieved this objective, not through superior tactics or strategy, but through superiority in the field of science.”

America’s victory in the Space Race was also a triumph for the alignment of military and civilian minds. Almost all our current information and communications technologies, like programming and microchips, stem at least in part from American government funding from the 1960s and 1970s. Everything from personal computers to video games to the internet owe their existence to this period of investment.

Much of this progress was channelled through DARPA, the US government’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, which is still a heavy investor in new technologies such as artificial intelligence, machine intelligence, and semi-autonomous systems. It’s little surprise that the American armed forces are, at least until recently, global leaders in military technology.

The world is now entering a new stage of warfare, one which will be even more tech-centric. There is little doubt, for instance, that Artificial Intelligence (AI) will play a critical role on the battlefield of the future, providing those countries that master its use with a devastating advantage. As Vladimir Putin once declared, “whoever becomes the leader in this sphere will become the ruler of the world”.

The US state department assesses that a key function of China’s MCF programme is to help the PLA to become the first military to transition to AI-powered “intelligent warfare”. For example, an algorithm that can be used to work out when a friendly soldier wanders into the line of fire can also help self-driving cars to avoid knocking down a pedestrian that walks into the road.

There are many in America who recognise that civilian technological expertise is needed to give their military the AI edge. Unfortunately, and in stark contrast to the joined-up approach of China’s MCF imitative, it appears that many of America’s scientists today don’t have the desire to help with their country’s military development.

In April 2017 the Pentagon announced the launch of Project Maven, a study that would use artificial intelligence to best distinguish people and other objects on the battlefield. Google, one of the world’s leaders in AI, soon signed up.

But not for long.

In April 2018, the New York Times published a petition by 3,100 Google employees opposing their company’s partnership with the US Department of Defense. “Dear Sundar,” the petition read, “We believe that Google should not be in the business of war.” Such was the pushback from their employees that Google left the project a few months after the petition was aired.

What made this particularly galling for the Pentagon was that whilst Google was saying no to them, it was saying yes to its potential battlefield foe. In June 2018, Google and Apple sponsored a contest at the world’s top computer-vision contest, the Robust Vision Challenge. The challenge was for the entrants’ algorithms to make sense of camera images collected under weather different conditions, perfect training for the missiles or autonomous fighting vehicles of the future. The contest was not won by an American start-up, or even a Western researcher. Instead, Google and Apple’s prize went to a team from an institution very much in the American government’s sights: China’s National University of Defence Technology, an affiliate of the PLA.

Thankfully for the Pentagon, not all US tech companies are squeamish about helping their country’s military. In 2020 both Microsoft and Amazon bid to win a $10 billion initiative known as the Joint Enterprise Defense Infrastructure, or JEDI, a cloud computing solution intended to give the military better access to data and technology from remote locations. Microsoft eventually landed the contract, but it wasn’t a victory that was welcomed by many of their staff.

Not wanting to help the military is not just an American problem; influential voices across Western science are trying to limit scientific involvement in military research. The British-based journal Nature opined in a 2018 editorial that governments asking universities to help develop weapons was “a threat to the culture and conscience of researchers”.

180 years on from the public-private devastation wrought by the Nemesis, it is now China who leads the way in using its economy to bolster its forces. It is not the only example of China showing the West what can be achieved with a national plan backed up by private enterprise. In much the same way that the Digital Silk Road has been a success, thanks to the blend of state support and corporate know-how, MCF is transforming the Chinese military.

America and the West reaped great rewards by bringing the military and civil together in the middle of the twentieth century, and there’s no reason why they can’t be inspired by China to do the same in the coming decades. The trick is in persuading the civilian techies to help.

It’s somewhat ironic that the academic activists who hold back their talents from military development rely on the freedom that the West provides to make this choice - a choice that wouldn’t be available to them under the Chinese dominance that their actions are doing so much to facilitate.

Very interesting as always Sam. A minor correction is that the Nemesis was not in fact a Royal Navy ship (so not 'HMS'). She was an East India Company vessel, which underlines rather nicely your point about civil-military fusion and the important role of the private economy in developing and funding military technology. The Royal Navy was rather suspicious of steam to begin with, so in this case the initiative was taken by the Company, which was less hide-bound in its attitude to new technology.

Great piece, Sam, though I thought your final paragraph somewhat at odds with the balanced tone of the rest of the article. It’s not necessarily unhealthy that in established capitalist liberal democratic economies there’s an unwillingness on the part of companies to participate in the defence industrial complex. In the past this has been easier to justify where there is a clear and present danger to defend against: is that in your view now the case with China? Aside from Taiwan and the South China Sea, do you see China as militarily threatening broader interests?