Hello and welcome to What China Wants.

There are many ways to measure the success of China’s growth. This might include its military might, or its diplomatic reach, or its dominance of the United Nations. But there is one metric that is always considered the top of the pile when it comes to international comparison, and that is wealth.

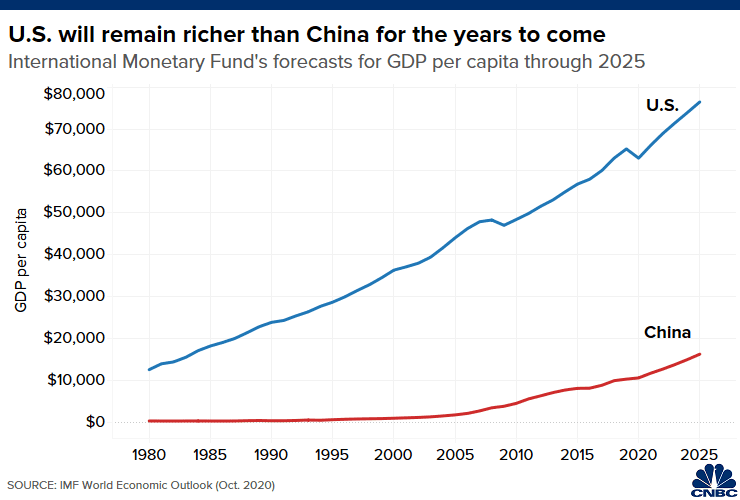

For a number of years there has been a popular conception that China is bound to become the richest country on Earth. In one way - GDP PPP - it is, beating the United States by $23.5 trillion to $21.4 trillion, according to the World Bank.

But what really counts is how wealthy is population is. There’s an apocryphal story that dates from when Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet Premier, visited California in 1959. As the plane took off from Los Angeles, he looked down at all the swimming pools and realised just how wealthy the American people were - and what that meant for out-competing the US model.

Despite its internal woes, America remains a phenomenally rich nation, both nationally and per capita. China, however, fares badly in its per capita measurement, registering just $16,800 per person compared to $65,300 in the US. There are, after all, a lot of people to share the wealth around in the People’s Republic.

As such, China is classed as a middle income country. It wants to be a rich one. Can this ever happen?

Today I publish an interview with George Magnus. The author of Red Flags: Why Xi’s China is in Jeopardy, George spent a life time as an economist in banking before joining the Oxford University China Centre. His book explains why China, far from being all perfect, has a number of “red flags” that its leaders need to address if it is to meet its full potential - for example, breaking out of what is called the Middle-Income Trap.

As always, please do consider sharing, commenting, and liking.

Many thanks for reading, and I’ll be back on Saturday with more from the History of China series.

(PS - for those of you wanting to know what the Biden-Xi talks just now were all about, and their impact, I’ll be back with more on that next week once the dust has settled.)

***

Sam Olsen: What is the Middle-Income Trap?

George Magnus: In basic terms, the middle-income trap is where a country manages to grow out of poverty and attains a certain income, but then gets stuck at that level. It could be that it loses its competitive advantage, such as cheap labour, that helped it achieve middle income in the first place.

From the point of view of economic development, we know that there are certain things that need to happen in order to see a country’s economy take off. This includes access to capital, or to labour, and so on, and as the country steps up the ladder it propels the economy. But the problem is, as we look at China, there are certain things you can only do once: you can only enrol your children in school once, transfer labour to high productivity manufacturing once, build the world’s largest housing market once, join the WTO once and so on and so forth. And the CCP did these things, earning its spurs in doing so.

The CCP was also happy to step back and allow the economy to grow, influenced as they were by the work of the Hungarian economist János Kornai, who helped introduce concepts fundamental to successful growth like hard budget constraints.

Analysts acknowledge the correlation between reform and the increase in the concept of total factor productivity. TFP is a measure of technical progress and the efficiency with which labour and capital inputs are combined and exploited. So good reforms will boost TFP, which did happen in China - for example the privatisation of state enterprises and the reform of the housing market, and the preparation for the WTO accession between 1993 and the early 2000s.

But TFP had gradually ground to a halt by the time the financial crisis happened in 2008/09, after a decade in which the impetus of reform had ebbed. After the crisis, China reverted to a more debt-linked growth model, and few major reforms were introduced. Under Xi Jinping, liberal and market reforms have pretty much stopped.

To avert the middle-income trap, China needs productivity growth, and that in turn requires reforms which the government is not considering.

SO: But isn’t it recognised that China, because of its size, industriousness, and recent growth record, will continue to grow? Doesn’t this mean it is destined to escape the middle-income trap?

GM: First of all, it’s important to note that “the unstoppable rise of China” is a construct created by Beijing. Under Deng Xiaoping and later leaders, China really did open up to the rest of the world, and to foreign firms and learned to adapt aspects of capitalism into its own state-led economic template. Now though, this “unstoppable rise” rhetoric rings a little more hollow.

China’s growth is threatened by Beijing’s hubris. It’s fair to say that the Great Financial Crisis in 2008 was like a lightbulb going on for Beijing, which saw that the American and Western economic model was flawed – and that this was an historic opportunity for China to exploit. The CCP has been doing this ever since, aided and abetted by the Trump presidency, and at least the early stages of the pandemic.

But by 2021, I think we can say that China is now having to manage its own errors, pushback in many countries abroad, and criticisms even among some of its own senior officials. The problem with these criticisms is that protagonists don’t really have the ear of Xi Jinping.

SO: What does China need to do to stand a chance of avoiding the middle-income trap?

GM: The problem is, understanding what needs to be done, and actually getting it done, is hard to do in China because of political sensitivities.

In terms of what China needs to do, to put it simply, it has to embrace a new development model. I think the authorities recognise this. But it is hard for them politically to proceed in the ways that most development economists would advocate.

So, for example, SOE reforms, liberalising the hukou or urban household registration system, income and wealth redistribution from the state to households, and progressive tax reforms and social welfare expansion are all things the government could consider to change the model. But these are difficult for the CCP to do, or even impossible.

Partly this is because of the socialist values being pushed hard by Xi, in the so-called Red Reset. This puts the state and state enterprises and the party as the main driver of growth.

Whilst the private sector in China is vibrant, it has a different relationship to the state compared to the UK or the US. Private firms in China have, since last year, been increasingly pressured to align their interests with those of the party and state. Party committees and members have been urged to take on important management and compliance functions and entrepreneurs “encouraged” to make donations to party projects as part of the newly emphasised Common Prosperity campaign. it’s almost like private firms are being taken over by the state from the inside.

The problem for Xi’s China is that there is no empirical evidence to say that this kind of approach will succeed, and no totalitarian, centralised nation has ever broken the middle-income trap. China could be the first to do this, and it is possible that modern complex economies confer advantages that we haven’t been able to measure before: data driven economies, digital technologies and advanced systems and products could, for example, bestow advantages to a state run system that have eluded them until now.

And yet – the CCP recognizes that innovation is super important to the development of the economy. But innovation is a dynamic bottom-up change, challenging the consensus, which spills out into all parts of the economy to drive growth. Innovation is fundamentally a business process that needs to permeate from the original sources of technological breakthroughs to the periphery of the economy. It isn’t just about Alibaba and Huawei. Real innovation through the economy is most likely to emerge from a vibrant private sector that doesn’t fear change and instability the way that the CCP does.

SO: China is famously challenged by its demography, but what role does this play in its middle-income trap prospects?

GM: The slump in fertility down to 1.7, which is way below the population replacement rate, means that the working age population is contracting. At the same time China is dealing with an ageing population.

China is the fastest aging country on the planet, with its Old Age Dependency ratio almost doubling in the last decade. By 2040 China will be a significantly older country than the US.

This is a major issue for Beijing because the country will reach Western-style ageing metrics at a fraction of the wealth of the West, and with a much less developed social welfare system. China’s unfunded pension liabilities are at least 140% today’s GDP, which is not dissimilar to many OECD countries.

There are other structural demography challenges too, such as a massive gender imbalance thanks to the one-child policy years. And over the next few years there will be a massive slump in women of child-bearing age, which will add yet more pressure.

SO: What can Beijing do about the demographic impact on the economy?

GM: Basically, China needs to develop coping mechanisms, but it is loathe to. They could increase immigration to relieve the downward pressure on the working age population., but this is very unlikely to happen. They could also increase participation of female and elderly workers, for example increasing the pension age especially for women from 50 or 55, depending on the type of work done.

They need also to focus on raising productivity, exploiting technology and reforms to make up for the shortfall in workers. But advances in technology may also be destructive in terms of employment creation especially if the workers are lacking in skills and education. Educational attainment for example is a very important shortcoming. As revealed in the recent book by Scott Rozelle and Natalie Hell [Invisible China: How the Urban-Rural Divide Threatens China’s Rise] only around 30% of workers have more than a high school education, compared to 50% or more in the West, which makes it tough for companies to be able to fully exploit new technologies.

It’s important to ask what happens to a country with an ageing, gender-skewed population where 60% of workers are in low pay, low skill jobs, and thanks to low educational attainment, without many prospects. And one which traditionally looks after elderly relatives in the home.

SO: How will we know if China has broken through the middle-income trap?

GM: The longer China remains a middle-income country, the more likely it is that we will be able to say it’s trapped. China’s GDP per capita [$10,500 in 2020] is only slightly higher than Mexico’s, which is acknowledged by many to be in the middle-income trap.

Getting out of the trap, or avoiding it, is widely reckoned to be about having robust and flexible institutions that allow people to operate at higher levels of productivity than they could do otherwise.

So it is important to think not only about China’s economy and its firms, but also its politics. Put simply is Xi’s China willing an able to embrace the type of reforms that will allow such institutions and practices to develop, or is it on a different political path altogether? A lot of people would say the latter, I suspect, and that makes the 2020s a very tough decade for China.