A Geopolitical Review of 2024

8 major events of the the last twelve months that will resonate for years to come

Hello and welcome back to What China Wants.

In geopolitical terms, I think it is fair to say that 2024 has been an interesting year. So much has changed, and to be frank we are in a far more dangerous place than we were at the end of 2023.

To mark the passing of the year, in this post I go through some of the most consequential geopolitical events of the last twelve months. (Do you agree with me on these? Are there others I should have added? As always, feel free to add your thoughts in the comments, or send me a message.)

Before I continue, I want to thank you all for reading What China Wants. After its relaunch earlier this year it has continued to go from strength to strength, adding new readers almost every day. Substack is a great platform for geopolitical writing, and there’s such a plethora of good writers on it now that I feel privileged to be read by so many of you.

I have also received a bucketful of messages discussing the posts, some agreeing with me, some arguing against. Such is the importance of understanding what’s going on around the world, especially where China and Great Power rivalry are concerned, that the more conversation I can generate through What China Wants the better.

So, thank you. I look forward to providing many more thoughts on China and the changing world order in the months and years to come.

I hope you all had a Happy Christmas, and I wish you a great New Year. Here’s to hoping 2025 won’t be as bad as I think it might be…

Sam

1. China and US move further along the road of confrontational decoupling. Ever since the launch of the first trade war by Trump in 2018, there has been a blizzard of financial sanctions placed on Chinese companies and individuals. At first, China didn’t respond much, even as more and more sanctions were rolled out under President Biden. But now the US has started obviously targeting Chinese tech firms with the stated aim of putting back their tech development, so China has begun responding with sanctions of their own. In October, for instance, Washington announced that it was finalising rules to limit US investments in artificial intelligence (AI) and other tech sectors; Beijing quickly announced export restrictions on “dual-use” technologies for both civilian and military use, including on metals like gallium that are important for semiconductors and specific military uses.

What started off as Trump pushing back on what his Administration saw as the nefarious impact of China on the US economy, has now morphed into a cycle of confrontational disengagement. The aim of the game seems to be to attempt to cripple the other’s tech development. 2024 was when the gloves really started to come off, and we will almost certainly see things deteriorate in the year(s) to come.

The problem for the US is that China now has such control over the supply chains of technology products, both old and new, that it is going to be hard – very hard – for the US to win this cycle of tit-for-tat restrictions. What makes the problem even more high stakes is the strategic import that Beijing has placed on being the globally dominant player in the technologies of the future. But what Trump started six or seven years ago now, he will continue, with significant consequences for both sides (and all of us in-between).

2. China’s move to New Quality Productive Forces

2024 also saw China double down on its push towards what could be one of the most important changes to the world economy, namely New Quality Productive Forces.

In a recent post I discussed how Xi is trying to reinvent what it means to be an economy by harnessing new and emerging technologies like AI. Beijing sees world dominance of the Fourth Industrial Revolution as fundamental to its strategic aims of being a world power, in the same way that the UK became one through control of the First, and the US the Second and Third Industrial Revolutions. A central plank to this ambition is the development of technology-based New Quality Productive Forces.

Assuming this works – and it is by no means certain that NQPF will work – it could be a game changer in both international economy and international relations. As I argue, achieving a new type of economy will give Beijing even more economic power globally.

3. BRICS Expansion

2024 saw the biggest expansion of the BRICS organisation as Iran, Egypt, Ethiopia, and the United Arab Emirates all joined existing members Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. Saudi Arabia was also invited to join, but is still considering whether to do so or not.

Although the BRICS organisation is informal, without a centralised structure or headquarters, it does represent a bloc that stands counter to the West. It also has regular meetings, including one in Russia in October 2024 that led to the Kazan Declaration – a potentially momentous event in the evolution of the world order. The Kazan Declaration made it clear that the BRICS organisation would now push to create an international financial system that was free from US influence, which would please many countries around the world worried about being beholden to Washington. (Somewhat incongruously, the Kazan Declaration also had a clause on the preservation of Big Cats, but India insisted on it being there.)

If the BRICS organisation continues to grow in terms of members and structure, then 2024 is likely to be seen as the year that it moved from theoretical grouping to physical bloc.

4. Iran Humbled. China is the leading partner in BRICS and the Counter Alignment, those nations determined to replace the current US-led world order. 2024 wasn’t the best of years for some of the other Counter Alignment nations. Iran has been bloodied by Israel and militarily humiliated: its air defences were destroyed by Israeli planes, its missiles mainly failed to penetrate the Iron Dome, and its proxy forces in Hamas and Hezbollah decimated. But Tehran still has irons in the fire. Their other proxies, the Houthis, continue to menace the Red Sea, and there has been a steep rise in ships avoiding the Red Sea as a result.

The fall of Assad though was a major blow. His Syrian regime had been propped up by Tehran for years, and the loss of their ally will make it harder to achieve their goals of regional dominance and the destruction of Israel. With Trump almost certain to cause more problems for Tehran, 2024 may have seen the beginning of the end of the regime’s local influence – maybe the end of the regime itself.

5. Russia and the Changing War in Ukraine.

The overthrow of Assad was also a blow to Putin, for reasons of prestige but also the potential loss of the Tartus naval facility, their sole Mediterranean base.

2024 wasn’t all bad for Putin, however. He has managed to keep the West from fulling committing to Ukraine, and as such his meat grinder tactics are working (albeit with the loss of hundreds of thousands of men). Indeed, this was the year that the tide begin to turn against Ukraine. It is far from certain that the country will capitulate, but the recent announcement by President Zelensky that his troops lack the strength to retake Russian-held Donbas and Crimea is a significant moment in the war. With Trump saying that he could “end the war in a day”, Kyiv has been boosting its diplomatic efforts in Washington and elsewhere, but it might be too late for them to go back to the ante-bellum borders.

6. Trump Re-Elected. In a year of elections – there were 74 national elections held, reportedly a record – the most impactful was the US one. It is now clear that Trump is looking to transform things both domestically and internationally. We are already seeing the impact of just two expected policies, namely the introduction of tariffs on all imports into the US, and the demand that NATO countries increase defence spending to at least 3% of GDP. It is far too early to tell what the details will be of Trump’s new term and how this will change things, but it is certain that change will come. If we compare this to Xi’s planned rewiring of his country (and thus the world) through his New Quality Productive Forces plans, then we can see how important this year has been from a strategic point of view.

7. Continued Turbulence in Europe. With the US and China talking of massive, once-in-generations change, Europe does nothing but plod on. No, it’s worse than this. The EU in particular is now weaker than it was has been because of the disharmony that has increased over 2024. Relations between EU members are strained, and the East-West divide as prevalent as it ever was (as this academic paper discusses). The failure to come up with an easy EU-wide response to Russia, with the disruption led by Hungary, is just one of the many fault lines that exist between the nations. And the December 2024 meeting between Slovakian Prime Minister Robert Fico and President Putin is unlikely to have gone down well with EU and NATO allies.

Many EU states have increasingly difficult domestic situations too, including France and Germany, who are both riven by political instability and a rise in extremism. Other countries, like Romania, Austria, and Slovakia, have also seen politicians friendly to President Putin become winners (or near winners) at the national level.

What this means in geopolitical terms is that it is proving harder and harder for the EU to act as a geopolitical entity. With so many issues facing the bloc – from immigration to Chinese economic competition to how to deal with Trump 2.0 – it looks probably that internal and external coherence is going to be under even more strain in 2025. While the US and China look to build towards the future in 2025, Europe will spend most of its time putting out fires.

8. More War. 2024 was a year of war. There are now 110 conflicts around the world, the bloodiest times we have seen for decades. This includes wars of the utmost savagery that barely make the news, including Sudan, with more than 61,000 casualties, maybe many times more – and where Russia and Iran are playing a key role. It is almost certain that 2025 will not see a reduction in this level of conflict; I fear the reverse will in fact be true.

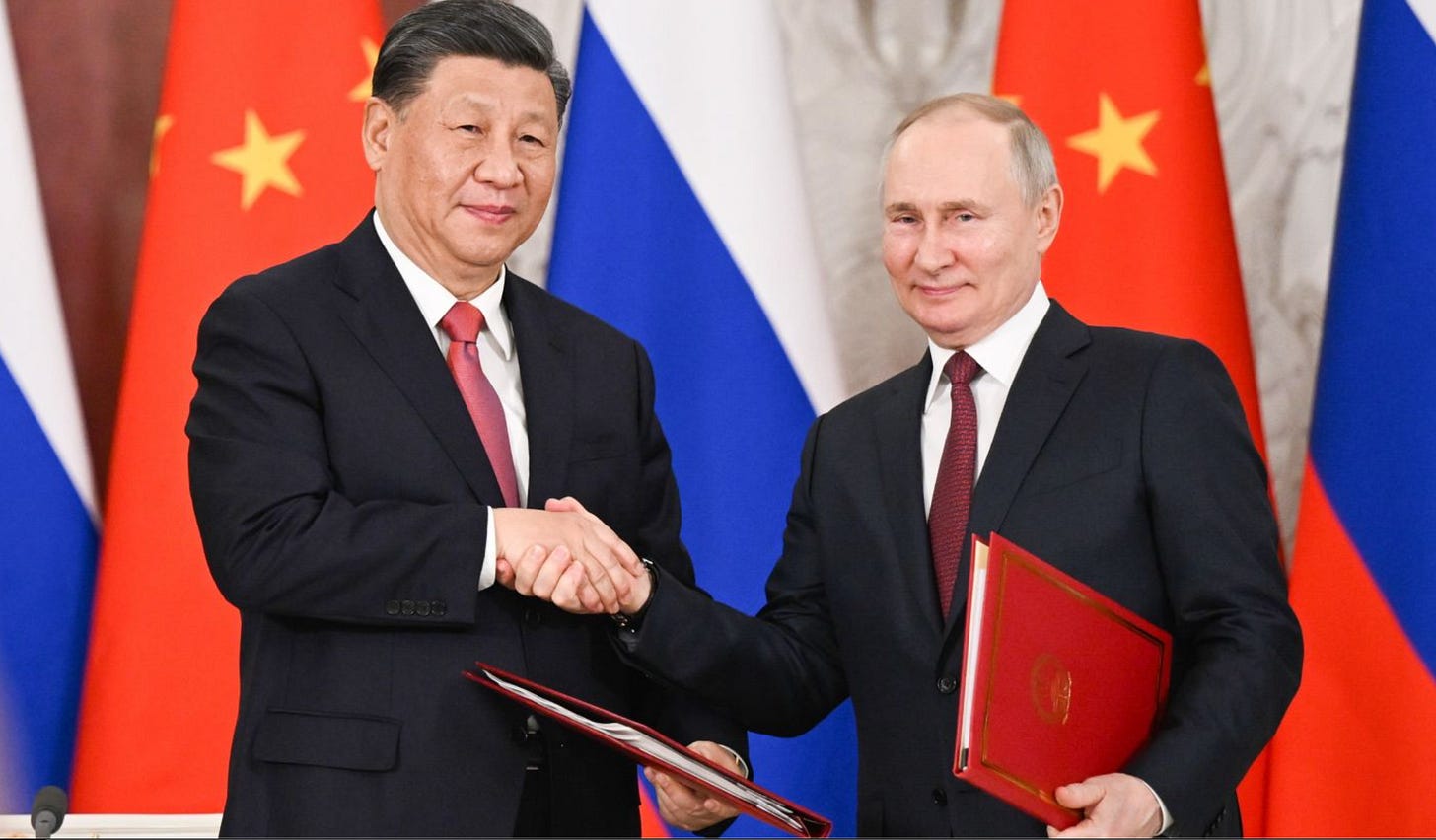

In sum, 2024 was a strategically important year in geopolitical terms. When, in 2023, Xi said to Putin that “Right now there are changes – the likes of which we haven’t seen for 100 years – and we are the ones driving these changes together” he couldn’t have been more correct, as 2024 has shown.

Now throw in Trump, the regional chaos of the Middle East, political difficulties in Europe, and the huge number of conflicts, and we can see that things aren’t going to improve anytime soon.

Alas, 2025 is unlikely to be much better than 2024. But if change is what you’re after, then you’re almost certain to have your fill of it in the twelve months to come.